The Electoral College explained

President Trump was one of five U.S. presidents that won the presidency after losing the popular vote. Since 2016, many politicians and voters have called for a change to the Electoral College system that would ensure a president wins by a more direct vote. We broke down what exactly the Electoral College is, and why we have it.

October 6, 2020

When voters head to the polls on Election Day or send in their absentee ballots, they will actually be voting for a slate of electors bound to their party’s ticket.

The Electoral College is a complicated system established by the Constitution tasked with formally electing the president and vice president. The framers intended for this system to serve as a buffer between the American people and the presidency.

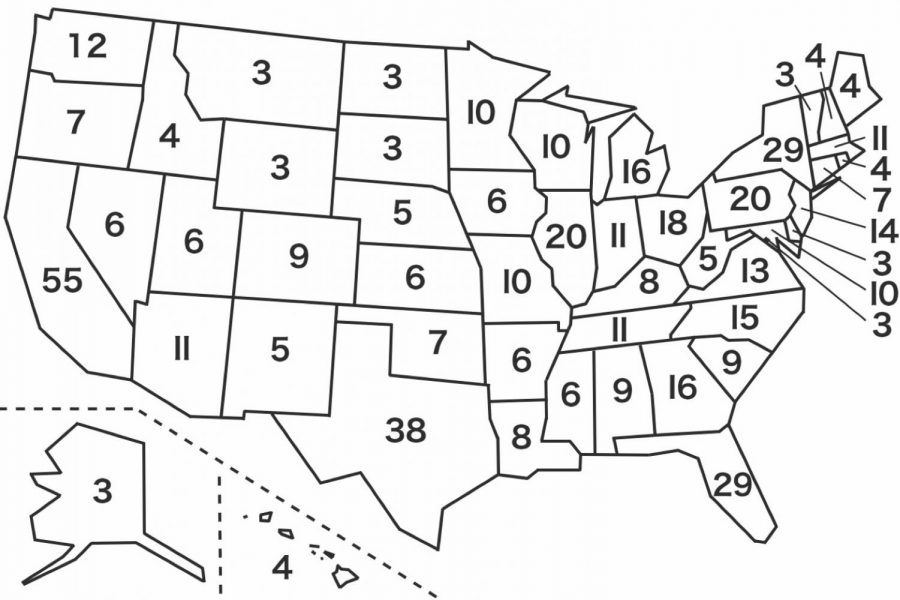

A presidential candidate needs at least 270 electoral votes to win out of a possible 538. Each state has as many electors as it has U.S. Senators and Representatives. So, Iowa has six electoral votes in the Electoral College.

As we saw in 2016, a presidential candidate can lose the popular vote and win the Electoral College, thus winning the election. Including President Trump, only five U.S. presidents in history have won the presidency after losing the popular vote.

The body of 538 electors is formed every four years on Election Day and cast votes at their state capitals in December. Whichever party’s candidate wins the statewide popular vote on Election Day, the state will send their respective slate of electors to their state capital so they can formally cast their ballots.

Traditionally, the electors — who are sometimes chosen at state nominating conventions, by party leadership, or in other, randomized ways — will give the stamp of approval to whichever presidential candidate won the popular vote in their state.

Twenty-six states and the District of Columbia require their electors to vote for the candidate that won the state plurality through oaths and fines. In 2016, seven electors voted against their state’s plurality for president and six did so for vice president. However, these “faithless electors” have never decided a president or vice president, according to the U.S. House of Representatives history archives.

Trump won the Electoral College in 2016 with 306 electoral votes — so 306 of those electors were Republican — and Hillary Clinton received 232 electoral votes from Democratic electors. Trump lost the popular vote by nearly 3 million votes.

Populous states like California, Texas, and Florida, are highly valued because they have larger numbers of electoral votes to award. These states are crucial in securing a win, along with traditionally swing states like Ohio, Wisconsin, and Michigan.

RELATED: Iowa political leaders question the productivity of the first presidential debate

Because of this system, campaigns will spend more time, money, and resources in states with a large number of electoral votes, including the states where they think they have a chance of swinging the electorate.

In smaller states with less electoral votes, like Wyoming and its three electors, each of Wyoming’s three electoral votes corresponds to 177,566 people compared to the national average of 565,166 people, according to FairVote. This gives voters in Wyoming more than three times as much clout in the Electoral College than the average voter.

According to an analysis from National Popular Vote, a non-profit organization that advocates for a system that better reflects the popular vote, two-thirds of all general-election campaign events in 2016 took place in six states — Florida, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Virginia, and Michigan.

The data, compiled by FairVote, defines a “campaign event” as a public event where a candidate is soliciting state’s votes, such as rallies, speeches, town-hall meetings, and other public appearances.

Fifteen states are a part of the National Popular Vote interstate compact — an agreement, which was approved in the respective state legislatures, to give the states’ electoral votes to the candidate that receives the national popular vote, regardless of which candidate wins that state. This compact goes into effect “when enacted by states with a majority of the presidential electors—that is, 270 of 538,” according to National Popular Vote.

After the compact goes into effect, “every voter in all 50 states and DC will acquire a direct vote in the choice of all of the presidential electors from all of the states that enacted the compact.”

Some politicians, like Sens. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., and Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., and their supporters have said they want to abolish the Electoral College and replace it with a new system that would treat every state equally.

This sentiment didn’t only emerge out of the 2016 election — in 1970, the U.S. House of Representatives approved a constitutional amendment to abolish the Electoral College and replace it with a more direct system. This was after Richard Nixon narrowly won the popular vote but won a large margin of the electoral votes.

The amendment was later struck down in the Senate after a filibuster.

Joe Biden told The New York Times editorial board in December that he does not support abolishing the Electoral College.

University of Iowa political science professor Cary Covington wrote in an email to The Daily Iowan that it is unlikely Congress will ever amend the Constitution to ensure the winner of the national popular vote wins the presidency.

Covington wrote that the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact is a popular alternative to the Electoral College system, but said he doubts that compact will ever reach 270 votes.

“In light of these factors, I think we have to live with the prospect that rural, small-population states will continue to exercise disproportionate power over the Electoral College,” Covington wrote.

While some states have made changes to their individual voting systems, the last action in Congress to make a significant change to the Electoral College system was a joint resolution introduced in the U.S. House in January 2019. That resolution has not yet made it out of committee, signaling that a change to the 12th Amendment could still be ways away.