Ask the Author | Rebecca Solnit

Author, historian, and activist, Rebecca Solnit, discusses her writing career in light of becoming the eleventh recipient of the Paul Engle Prize from the UNESCO City of Literature, offering a reflection on her own work and enlightening bits of advice.

September 27, 2022

Rebecca Solnit is an American writer, historian, and activist. In a ceremony on Sept. 29, she will be awarded the Paul Engle Prize from the UNESCO City of Literature at the Coralville Public Library and discuss her work with author and editor Lyz Lenz. Solnit has written over 18 books on feminism, western and urban history, social change and insurrection, wandering and walking, and hope and catastrophe. Her books include “Recollections of My Nonexistence,” “Hope in the Dark,” “Orwell’s Roses,” and she recently launched the climate activism project “Not Too Late.”

The Daily Iowan: How did you feel when you found out you were awarded the Paul Engle Prize from the UNESCO City of Literature?

Rebecca Solnit: I was delighted, and it was a nice thing because I did not get an MFA. I did not go to a writing program, and so it’s always nice to be recognized by the program and by the system to validate that you can become a writer through other avenues as well.

DI: One of your recently published works, “Recollections of My Nonexistence,” is a memoir. How has it felt writing nonfiction about yourself?

Solnit: I made the transition to writing more personally a while ago, but this book felt more raw and unlike some of the earlier books like “A Field Guide to Getting Lost,” where personal experience might be a starting point or an ending point. It felt like testimony in a tribunal. I have been writing about feminism for 37 years, but I felt like so much of what I wrote was cast in an objective, journalistic way about either the aggregate impact of misogyny and violence against women or specific cases or special impacts. What never felt like it came into focus is what it might do to us individually to live in a world where we face many kinds of erasure or annihilation. Whether it’s being silenced or not believing in speech, or you simply don’t participate in things because of fear, whether it’s walking down the street late at night or expressing your real opinion. I wanted to really describe how it all played out in my formative years, and the book is really tracing a very personal and specific experience, which is becoming the writer that I became, and what I think is an almost universal experience, which is just being a young woman in a world where so many people want to harm and silence and control young women. In some ways, it was very satisfying to put it on the record, but also very personal to put some of that experience out there.

DI: Is there any piece of literary work you have written thus far that you are most passionate about, and why?

Solnit: There’s no one piece. I’m doing a climate anthology now, and I’m really happy to participate in addressing the climate crisis. The feminist work has had its impact, and I’ve been really proud and excited to participate in moving feminism forward. I think it made a great leap forward in the last 10 years or so. But maybe “Hope in the Dark,” if I was going to pick one thing. Trying to articulate a hopeful theory of change to recognize that ordinary people sometimes have extraordinary power to change the world, that the historical record tells us that it’s happened over and over, and that the very uncertainty of the future has room for hope and possibility in it. And hope not as optimism, which assumes that everything will be fine, which is a form of false certainty just like pessimism and despair are forms of false certainty. The work I’ve done since 2003 on “Hope” and continue to do with this climate book that I’m writing for the new statesman feels like the thing I’m proudest of.

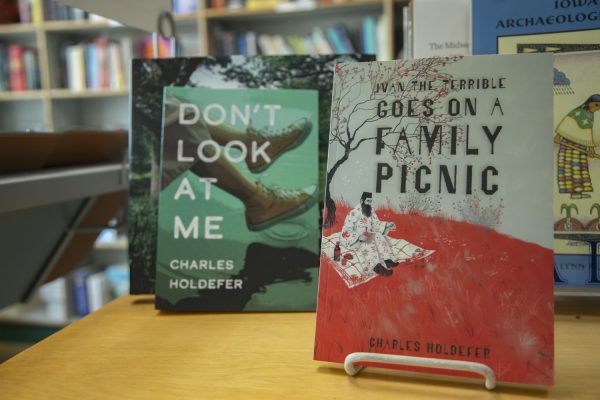

RELATED: Ask the Author | David DeGusta

DI: What is the biggest obstacle you have faced in your own writing, and how have you overcome it?

Solnit: I think one that’s still with me is work that is most significant to me and that I feel like is my most valuable contribution, rather than doing all the things everybody wants me to do. One of the fundamental truths of being a writer is that you will constantly be asked to perform different kinds of community service, help other people’s careers, participate in literary events, do all these kinds of busy work, and some of it’s valuable service, and I believe in it. But nobody will ever email you or call you up on the phone and say, “I really, really hope that you’ll stay home and write your deepest work from your most profound understandings and nothing else today.” Nobody will ask you to do that instead of all of the things that are distractions from them. So, ultimately, filtering out all that clamor to listen to what’s most compelling for me — which ultimately is my most profound contribution — has always felt like a challenge. I think that there might have been some things I would have really liked to write and I might, in some ways, have been a better writer if I had been less of a good girl meeting everyone else’s demands and expectations, and more just really focusing on my vision of what’s really important to say. I think everybody in whatever they’re doing in life has to strike a balance between a compelling personal sense and some sense of service, but I hope that my best work is itself a service, even though it’s not as direct as all the busy work.

DI: What is one piece of advice you have for aspiring writers?

Solnit: For anybody who wants to be a writer, I hope that you actually like writing and want to write and feel something urgent you have to say. The way you get good at it is you just do it over and over and read what other people write. You become a writer by writing, and you become a better writer by writing and looking at what you’re doing critically. Programs are great, teachers are great, books of advice are great, and workshops are great, but to become a writer, you have to write.