Westworld ends third season on a surprisingly happy note

Westworld’s third season delves deep into ideas of free will and ultimately decides that it is the best choice for humanity.

Aaron Paul in “Westworld” on HBO.

May 4, 2020

Sunday night was the season three finale of Westworld, and for the first time in the show, it ended on a possibly positive note for humanity.

The HBO TV show is about the robots, or “hosts,” in an adult theme park. The story follows their journey to consciousness, and how they attempt to find a place of their own. This season has stood out from its predecessors, feeling in the beginning as if it were a different show entirely. At the very end of the second season, the characters left Westworld behind for good and with it, the Western genre of the show.

In the third season, we find Westworld has been traded for the real world, and a solar-punk feel is introduced to the show. While at first I found this new look off-putting, it became extremely interesting and refreshing after an episode or two.

The season gives the audience new and striking visuals, abandoning the former wide pan shots of the American West, for futuristic images of Los Angeles reminiscent of the LA in Her. It even carries the same overwhelming, lonely feeling earlier on in the season, especially with the characters Caleb and Charlotte Hail, who often are shown feeling out of place and disconnected from the people and actions around them.

Despite these changes, the spirit of what the former Westworld once was is still there and doesn’t disappoint. While each season has explored new and intricate themes, like consciousness and different levels of reality, the show sticks to its core theme of choice in the third. This season’s manicure made its message more explicit than usual: “Free will isn’t free.”

RELATED:Luna Nera follows witches of a 16th century Italian town and their struggle to stay alive

No character grapples with the dilemma of the existence, or nonexistence, of free will better than my favorite character, the Man in Black — or as he is known in the real world, William. William has always been a man too lost in a fantasy, too deluded about his own self to know if his choices are his own. While his role was considerably smaller this season, it was executed perfectly.

While the first season is unbeatable in terms of its intricately-connected stories and characters, the third season takes an interesting shift to a more focused, linear approach. Intricately woven and constantly connecting plot lines are traded for more single character-focused episodes.

This style of storytelling works infinitely better for Westworld’s change into a more realistic, plausible future for humanity. It makes the viewing of it more personal and closely related for the audience, but also slows down the pace of the plot considerably. Westworld has always been a story that focuses on plot buildup, but the pace was slowed down too much for my liking.

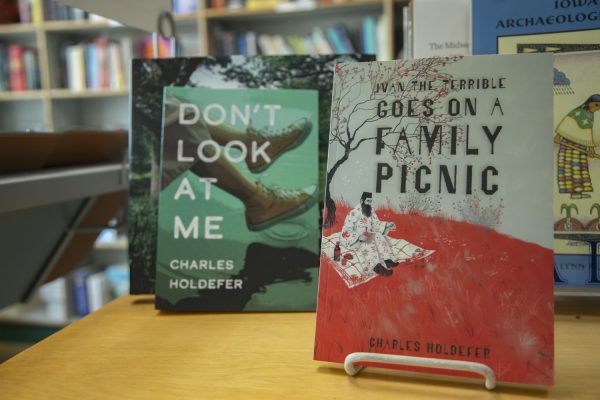

The new characters on Westworld captured a sense of greatness in this season, despite a few minor drawbacks. Actor Aaron Paul plays Caleb, but his character is difficult to distinguish from Jesse, his character from Breaking Bad — the similarities were so great that I called him Jesse for most of the season.

The villain, Sarac, and his machine that controls the fate of humanity were some of the most interesting elements of this season, featuring great backstories and engrossing ideas of the deprived nature of humanity, but I never felt like they had a chance at prevailing. In the seasons before, I felt as if anything could happen to any character — hero or villain — but season three felt like fate rather than the actions of any of the characters led to Sarac and his machine’s eventual fall.

Westworld ends to the scoring of Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon, featuring an unexpectedly positive Delores and positive possibility for humanity’s future. And yet I can’t help but feel as if there is more at play here, as if this ending isn’t really happy at all — it’s all just a momentary facade.