Protests, power, and paradigm shifts: How Suzanne Wright’s activism brought her to a career of creating powerful art

Artist and Grantwood Fellow Suzanne Wright spoke about how her art was heavily inspired by her experiences in activism, struggling to grapple with her identity and trauma.

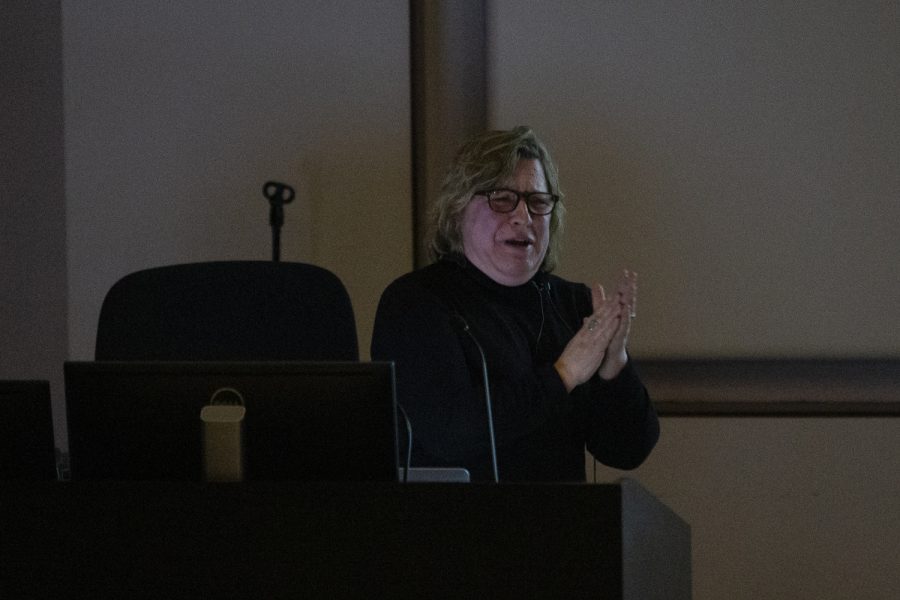

Suzanne Wright gives a lecture on her project “Goddess Eye View” on Feb. 20 at Art Building West.

February 21, 2020

Attendees of artist Suzanne Wright’s lecture “Goddess Eye View” thawed from the frigid cold in the lecture hall of Art Building West before the event began. Art connoisseurs and grad students alike all gathered to listen to Wright tell the stories of how she started her career.

Wright began her lecture by showing the audience a photo of her service dog, Gus.

“This is my visual ploy to endear you to me,” she said.

The artist then dove straight into how she got into her career and told stories of professors she had in college at Cooper Union. One professor exposed her to the “reality of brilliant people dying of AIDS,” she said.

“Activism is walking for people in their shoes,” she said as she discussed her experiences with protests. Wright joined ACT UP, a political group that worked to end the AIDs pandemic that kick-started her activism.

Wright was arrested a multitude of times for participating in die-ins, protests in which people lay down and pretend to die. She was part of protests in New York City that stopped the stockbroker bell on Wall Street for a day, a die-in that resulted in women being carried out of St. Patrick’s Cathedral on cots, and blocked the Holland tunnel with a human chain of about 140 people.

Wright recalled an experience caught on video where a group of protestors rallied in support of getting more beds put in the hospital in Chicago for women who were diagnosed with AIDS.

“Police wore masks and gloves as if you could catch it [AIDS], it was humiliating,” she said.

The day after the die-in, Wright said the price of AZT, one of the primary treatments for AIDS, was lowered.

She discussed other themes in her work and life, including “queering.”

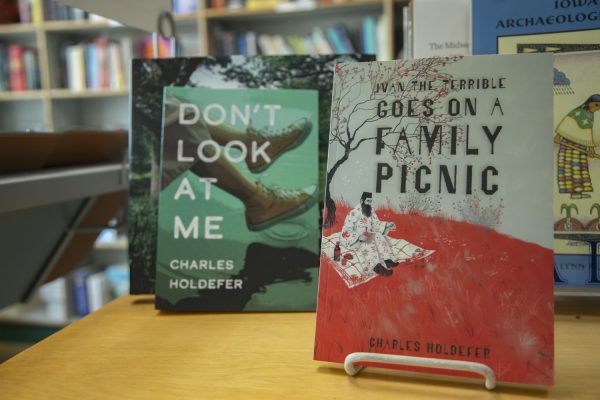

RELATED: Student Spotlight: Printmaker dives into themes of power, idolization

“[Queering] has different meanings for different people,” she said. “One of them for me is the sort of unknowable. It is the space in between things, the nonbinary, the undefinable. When you do start to define it or stabilize the meaning, you lose it.”

Another part of her early work was collaging structures that were considered powerful, such as the Hoover Dam, onto photos of women.

“How does one move past old hurts?” Wright asked. She reflected on these hurts in Upstate New York, dealing with homophobia and violence during protests.

Trauma and hope play a large role in Wright’s art. She considers disco balls a symbol of unstoppable celebration, hope, and possibility. One of her pieces, Rainbow Warriors — which was on display at the Port of Los Angeles — is a tribute to the Pulse Night Club victims. When viewers looked into a hole inside the piece, they could see a view of the Port outside.

“It was a hopeful alternative to the world outside,” she said.

Another paradigm shift occurred in 2016 for Wright, after the election and the women’s march. In lieu of those events, Wright decided that she wanted to feminize the Washington monument.

Towards the end of her lecture, she proudly displayed her feminized version of an aerial view of the Washington Monument titled Goddess Eye View.

The piece was painted with vinyl paint and acrylic paint on Birchwood. Goddess Eyes View is a vesica piscis, an intersection of two lavender-colored discs, accompanied by the colorful aerial view of the Washington Monument in the middle. Through this piece, Wright proved that with her passion for activism and reclaiming power, a “monumental perspective” is possible.