University of Iowa researchers at heart of developing vaccine

Of many moving parts to vaccine development, the University of Iowa’s researchers — and their mice — helped jumpstart the process.

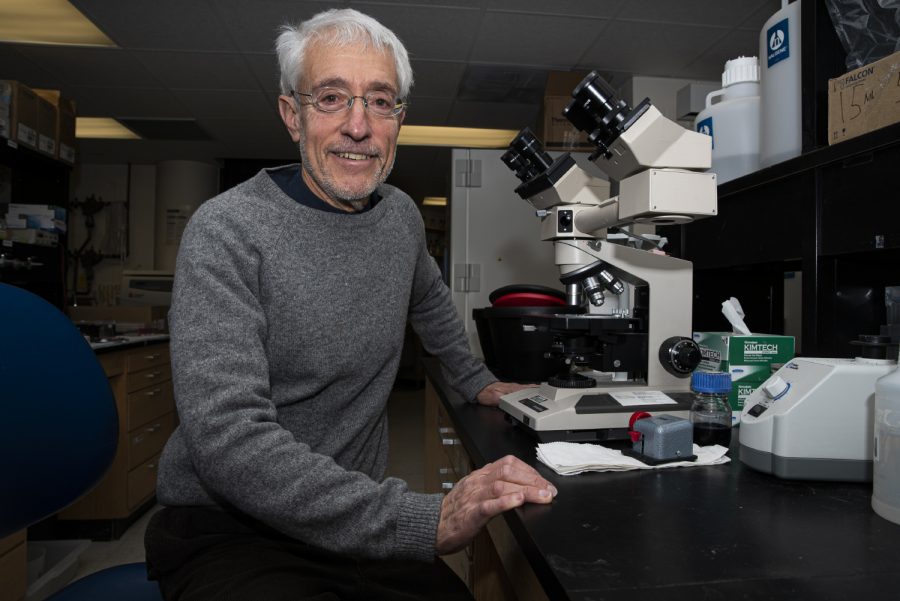

University of Iowa researcher, Stanley Perlman poses for a portrait in the Bowen Science Building on Tuesday, January 28th, 2020. Perlman along with staff at University of Iowa Hospitals & Clinics have implemented precautions following reports that a new coronavirus has been found in the United States.

March 17, 2021

A year ago, Stanley Perlman was one of a handful of researchers studying coronaviruses. Now, he estimates coronavirus researchers number into the thousands.

After the SARS outbreak in the early 2000s that infected more than 8,000 people faded, Perlman and his team continued what at the time seemed like relatively low-profile research, developing mice that could develop symptoms from a coronavirus.

Years later, those mice would be used to develop a vaccine now making its way into arms across the globe as one of the most effective tools in bringing the deadly pandemic to its knees.

At the start of the pandemic, researchers realized common lab mice, which don’t develop serious illness from coronaviruses, wouldn’t work for studying the new virus.

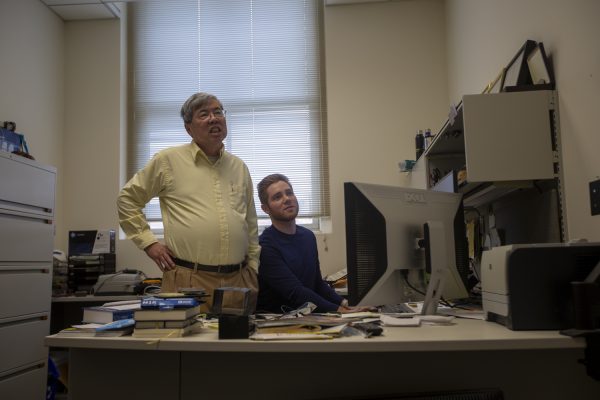

But Perlman and Paul McCray, a University of Iowa professor of pediatrics, immunology, and virology, had a solution in their lab — frozen mouse sperm.

Perlman and McCray in the early 2000s were able to use an adenovirus gene therapy vector that the mice inhale to deliver the human ACE2 protein into mouse airway cells. Once the mouse airway cells show the hACE2 protein, the mice become susceptible to infection with the coronavirus and develop symptoms, though not fatal, of COVID-19.

Perlman and McCray’s team shipped their stock to the Jackson Laboratory in Maine, which was looking for mouse models to make available to companies developing COVID-19 treatments and vaccines.

In another wing of the UI research hospital, Professor of Internal Medicine Pat Winokur started enrolling volunteers in a trial to test a new COVID-19 vaccine from Pfizer and BioNtech during the summer.

Now, the Food and Drug Administration has approved that vaccine and two others for emergency use — the Moderna and single-shot Johnson & Johnson.

Of those, Pfizer and Moderna are the first widely used messenger RNA vaccines. The speed at which they can be created safely, Winokur said, will change how vaccines are made in the future.

Messenger RNA vaccines give cells instructions to make a protein to develop an immune response. That’s instead of more traditional vaccines, which will put a weakened or inactivated germ into people’s bodies to develop an immune reaction in case the immune system comes into contact with a real virus.

That’s part of the reason the timeline for vaccine development has accelerated, Winokur told The Daily Iowan in an interview, and will likely be used more going forward.

“I think the success of the messenger RNA platform is going to allow us to create vaccines much more quickly,” Winokur said. “I think that technology allows us to adapt and create vaccines for variants.”

MRNA vaccine technology began being tested 15-20 years ago, Winokur said, and this was the first emergency-approved mRNA vaccine. She emphasized, however, that despite its speed, it underwent the proper research and testing.

Perlman, who sat on the emergency-use approval committee for each of the three vaccines that came before the FDA, echoed that sentiment.

However, Perlman said rollout and distribution likely won’t see the same sense of urgency that the COVID-19 distribution has employed for non-pandemic viruses. While more mRNA vaccines will likely be made because of the success of the COVID-19 vaccines, the distribution, testing, and logistics likely will not be altered as much.

“It will change vaccine development, for sure,” Perlman said. “Because these mRNAs seem to work very well. And they’re very fast. Making an mRNA vaccine takes like two days.”

Luckily, he said coronavirus is “really easy to make a vaccine against.”

“We didn’t know that when we started,” he said.

At about the turn of 2019 into 2020, cases of pneumonia began surfacing in China. Perlman said he called a few of his colleagues in China to try to see if it could be a new coronavirus — it was.

“I called some of them and said, ‘What’s going on?’” Perlman said. “When I got off the phone, I remember telling my wife, ‘this is a big deal.’”

His days didn’t slow down from there.

On one day in early March this year, Perlman said he started with a 7 a.m. call discussing the origin of the virus, then hopped on a World Health Organization conference at 9:30 a.m., and conducted Zoom meetings with his lab staffers until late in the evening.

That’s a typical day now for Perlman, who sat on the FDA emergency-approval board for the COVID-19 vaccines, using four decades of coronavirus expertise.

A year later, Perlman is studying loss of smell and age as a factor in developing severe symptoms.

“I think that we’ve all learned that you have to, we have to respect coronaviruses,” Perlman said.