A March made for women filmmakers

FilmScene’s Women’s March celebrates Women’s History Month by showing only female-made films for the month. The event represents the gradual march women have made over the years in their fight for equality.

March 13, 2019

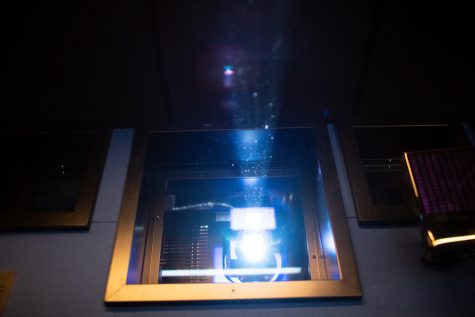

The rumble of speakers, the smell of popcorn, and the cool quiet of the theater, lit up by a projector. Going to the movies may not seem like a political act, but for the month of March at FilmScene, the local cinema brings the issue of gender equality to its silver screens.

The month of March is reserved to celebrate Women’s History. Many organizations use the month as an opportunity to highlight creative work done by women. With a new spotlight on female creativity, events such as Women’s March are helping filmgoers experience the stories not only about women but by women.

FilmScene dedicates the whole month for just that. FilmScene’s Women’s March celebrates Women’s History Month by playing only movies created by women, an event unique to FilmScene.

“I was really excited about it because I have never really heard of a movie theater doing this,” said Molly Bagnall, a member of the Bijou Film Board. “It’s really important, especially at this moment where there’s a lot of focus on representation. To just show all movies by women is great; it opens all these channels for special screenings that would normally not be screened.”

Rebecca Fons, the FilmScene programming director, played a key role in the making of Women’s March. She hopes that people realize the complexity of the event.

“I hope when audiences come to Women’s March, they aren’t just imagining they are coming to Women’s Stories,” Fons said. “I think our program indicates a larger breadth and depth that female directors tell on a regular basis.”

The movies being shown at Women’s March cover a wide range of topics and genres. The month includes films such as Destroyer, which shows Nicole Kidman as a hardened LA detective, and also films such as Rafiki, a Kenyan lesbian love story that was banned in its own country.

One of the featured films, Well Groomed, is coming directly from its world première to Iowa City. In the documentary, filmmaker Rebecca Stern examines female artists in the colorful world of dog-grooming competitions.

RELATED: Women’s March reaches Iowa City

“I think showing women artists and showing them with compassion and with prestige means something,” Stern said. “You can really only become what you see, so if you go and watch movies made by women who are showing women doing things that everyone else does, you can understand that these things are possible.”

Stern, along with other female artists, believes that this representation of female creativity is healthy for younger women to see.

According to womenandhollywood.com, while women compose around half of all moviegoers, out of the top 100 grossing films of 2018, they make up only 15 percent of writers and 4 percent of directors in Hollywood.

“It’s important because we’re a little over 50 percent of the population, and our perspective should be represented,” said Brittany Prater, the director of Uranium Derby. “It feels so important. The goal is to eventually get to the point where things are even between men and women.”

Uranium Derby is a documentary that covers the little-known role Ames played in the Manhattan Project.

“The film is a feature-length documentary, and it is centered on the role my hometown, Ames, played in the Manhattan Project, the making of atomic bombs,” Prater said. “I didn’t know about that history, but I uncovered it as I went. They had invented the first process of uranium purification there and were using Ames to purify the uranium made in the bombs.”

Along with Uranium Derby, other films at the event are documentaries. They include Stories We Tell, by Sarah Polley, a film that dives into the elusive truth of a family of storytellers, and Citizenfour, by Laura Poitras, a documentary that follows a massive government-surveillance program.

In Women’s March the variety in both style and genre of films further bolster the wide array of viewpoints included. For example, Prater said, war and war-related films typically come from a male perspective. However, her documentary is female.

“It’s been a complete hole, a missing perspective,” Prater said. “A topic like the Manhattan Project is often covered by a male. There are a lot of propaganda films, and it’s interesting, it’s changed.”

A feature of many of the films screened is an emphasis on emotional strength in women. Emotional strength can be more challenging to portray in film than physical strength, but directors such as Signe Baumane dive right into the challenge.

“When we look at history, we always think about heroic men jumping into battle with a battle cry on their lips,” said Baumane, the creator of Rocks in My Pockets. “I wanted to write about heroic women cleaning the house, and milking the cows, and feeding the children. I wanted to write about the internal journey of the woman. Surviving depression, even one bout, is just as heroic as jumping into battle.”

Baumane animated Rocks in My Pockets to show her family’s personal history with female depression. She finds it important to include the internal struggle women battle every day.

“I made the film because I’ve made short films before and thought I would like to make a feature film,” she said. “I’ve made some [short] films about sex, and I think that some people don’t talk about sex from a woman’s point of view. I am interested in expressing the woman’s point; it is a very underrepresented point of view.”

This use of media to show both external and internal lives is not new to art. Film has long been a way of showing different perspectives.

“I think engaging with media is a way we get trained in empathy and understanding others’ experiences,” said Emily Wentzell, a UI Associate Professor of anthropology. “So the wider the range of voices we have making the media, the better we get at empathy.”

The film medium can show different sides of life and spark newfound empathy toward others. It can help viewers find themselves represented as they normally wouldn’t have been in past mainstream cinema.

Women’s March covers both historical and current perspectives, and the films span almost a century of history. With the oldest produced in 1926 and the newest released this year, the films cover a breadth of role models from different generations.

“There’s a question of role models. When I was growing up, there were very few role models for young women,” Baumane said. “There were very few stories about women doing stuff, achieving stuff. It’s healthier for younger women to see women directors and women leadership and stories about women. Even stories about men but done by women have a different sense.”

One of these stories by a woman but about a non-female identifying person is They, by Anahita Ghazvinizadeh, which is about a young teen who is exploring gender identity while taking hormone-blocking medication. Another film, The Mustang, by Laure de Clermont-Tonnerre, follows a man in prison because of committing violent crimes who finds comfort when he trains wild horses.

Women’s March is not just about fitting female stories into the mold of already-written male stories. It’s about inventing new ones.

“We had a Wonder Woman and now a Captain Marvel,” Wentzell said. “But those are still like, OK, now we have put someone with a uterus in the male story. It’s not a much wider range of representing people’s stories.”

Organizers of the event want to emphasize that their choices don’t reflect the merit of other female filmmakers not included in the month’s lineup. With only a month dedicated to Women’s March, FilmScene had to choose a variety of female-made films in hopes of representing the widest range possible.

“Something you have to go against when it comes to Women’s March is [that] it can be like this tokenism of ‘how do you choose which films by women are important enough to play’ since you only have this one month,” Bagnall said. “What you play in that month suddenly becomes really weighty and feels like you’re making a statement with it.”

Including these voices and perspectives brings nothing but more creative and original art.

“The more diverse set of storytellers you have addressing a particular slice of life, the more you’re going to learn about it,” Wentzell said. “We’re all shaped by our experiences and socialization to understand the world in a particular way, and that comes through when creating fiction. It’s a lens in which you understand the world. The more diverse set of lenses you have, the richer the story telling.”

Fons said FilmScene tries to make it a priority to offer female-led films throughout the year, not just in the confines of one month.

“We have to remind ourselves that we don’t just do it in March and then we stop. It’s forces us to do it more and more throughout the year,” she said. “Ultimately, you’re going to the movies, you’re buying a ticket, you’re buying popcorn, you’re sitwting down, and watching a movie. So not every film is a message story — sometimes it’s just sit down and enjoy this film, and it happens to be directed by a woman.”