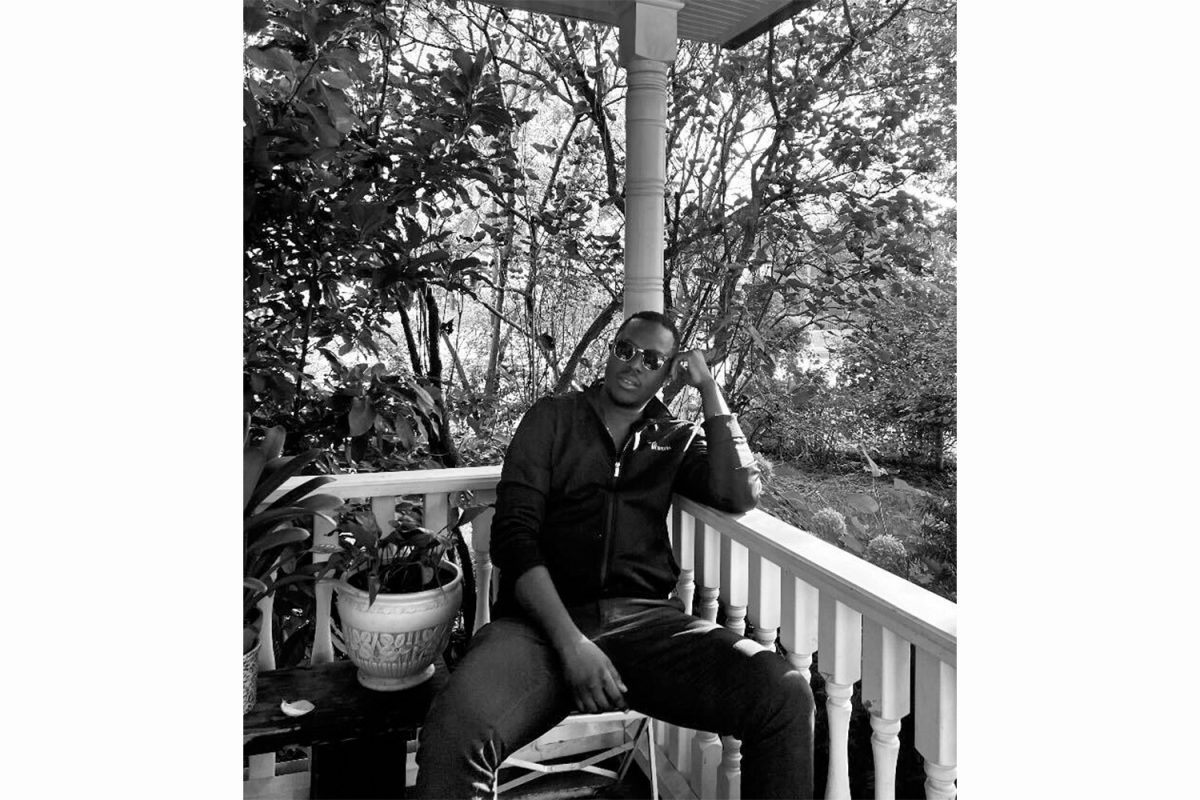

Oluwasegun Romeo Oriogun is a Nigerian essayist and poet. He is an Iowa Writers’ Workshop alum, debuting his career with a collection of poems titled “Sacrament of Bodies” in 2020. Oriogun also won the John Logan Poetry Prize for Poetry in 2020.

Oriogun is the first openly queer writer to win the 2022 Nigeria Prize for Literature with his book of poems, “Nomad.” He is the author of two chapbooks, “Museum of Silence” and “The Origin of Butterflies,” and his poems have appeared in the New Yorker, Prairie Schooner, Harvard Review, Narrative Magazine, and more.

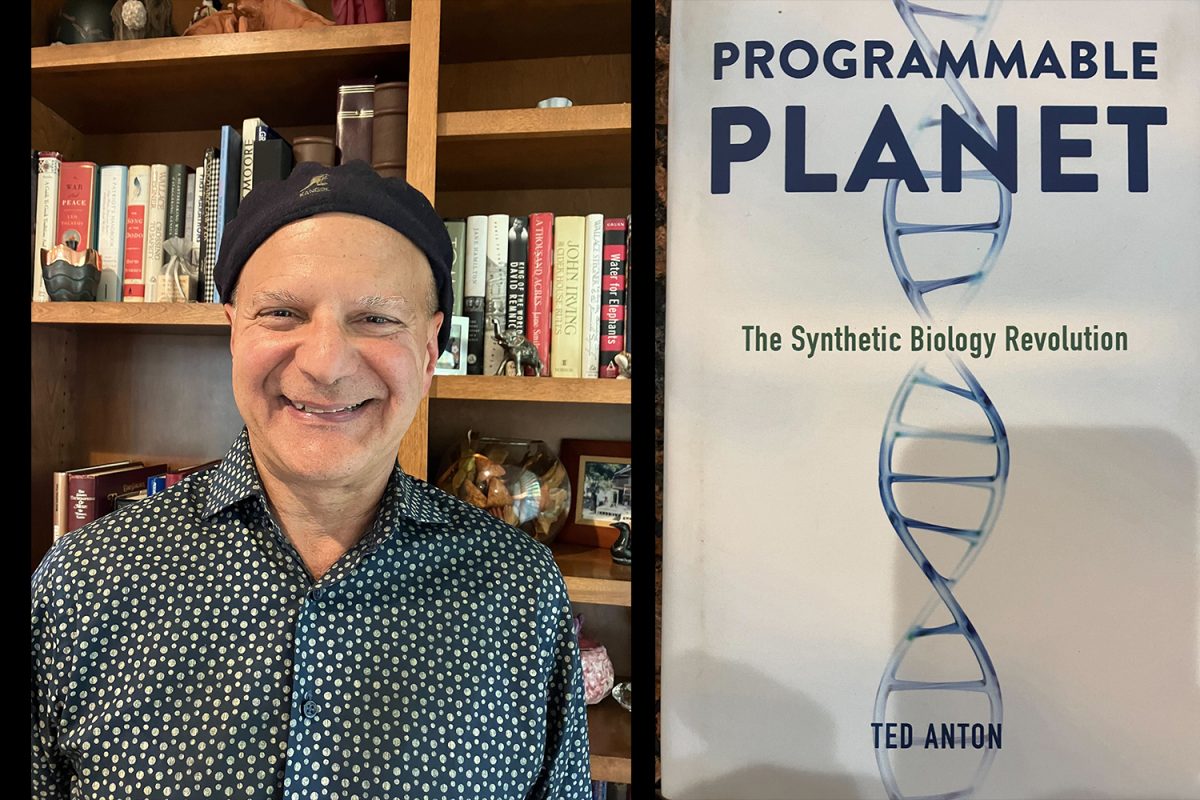

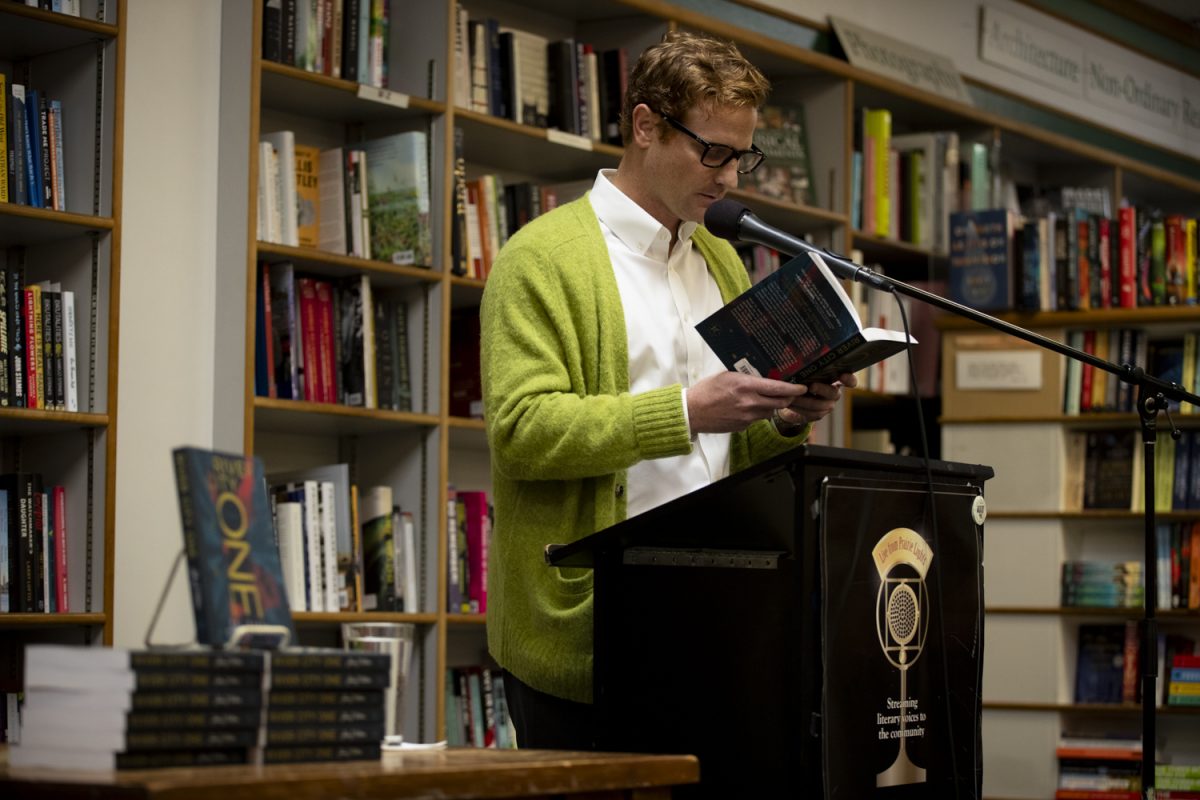

He read from his book, “The Gathering of Bastards,” at Prarie Lights Bookstore and Cafe on Wednesday. The book was a 2024 National Book Critics Circle Award Finalist in Poetry.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The Daily Iowan: In “The Gathering of Bastards,” there is a poem called “It Begins with Love.” Was this a letter to yourself as well as your readers?

Oriogun: It’s really interesting how different readers interpret poems. The poem was written in Ghana –– I was living in a community at that time where every time you come outside, something new is happening. Every single aspect of life, a good place, is capable of loving as much as despair. I wanted to write a poem that reminds me of that moment when everything reminds you of the tenderness of beginnings and love, and also how in an instant it can change into something else. It reminds readers of love.

Which of your poems would you say is your strongest and why?

I don’t think I’ve written a poem I’ve truly liked. That’s the sad truth, but it’s also what keeps me hungry to keep writing. Every poem I write is a curiosity to understand what’s happening around me or within me. Poetry is the only single place where I’m very organized. It’s not about if it’s the best poem. I’m trying to gather thoughts together, trying to get it through storytelling, narrating it into something that makes sense to me first before it makes sense to anybody.

How does the theme of exile weave through your poems in “The Gathering of Bastards”?

I left home in 2017. I was a young one. I had to leave Nigeria before coming to the U.S. and it was the first time I was leaving Nigeria. At the time I knew I would not be able to return quickly the way I would have loved to. The initial moment of despair, a little anger, was also through the poems.

The book starts that way. Every country has a dark side. In a way, all governments are also the same. People just want to be okay — to be free. Living in different countries taught me that. There is a way in which exile for me is trying to stay alive. Once you are in exile nothing stays the same. It’s a place of anchor that is no longer home anymore. It might be accents. It might be culture.

In the U.S. it seems to be less community, whereas back home it’s quite a common sight to be coming from work and be outside drinking with friends and talking about the day. You don’t even have to know them –– you can just join them and discuss, and its funny cause I look back home now and I would not be able to join that kind of gathering without feeling as if I’m an outsider.

What is one of your favorite lines from a poem you wrote?

There is a poem called “Fly Away” about going to a club with other Africans. There is a line that states, “We move between despair and salvation.” It’s my favorite line because you meet so many migrants here in the U.S. It’s always between those two things: either extreme joy or feeling like, where am I right now? It reminds me of what’s at stake. It also reminds me when I feel down that it’s okay. It’s a very ordinary line. It’s easy to have a favorite line.

How does “The Gathering of Bastards” compare to other works, such as “Coming Out” and “Battle of the Rams”?

“The Battle of the Rams” and “Coming Out” are part of a collection called “The Sacrament of Bodies,” which is officially my debut collection of poems. Those are poems for me to understand who I was as a bisexual man in Nigeria. No matter how difficult it is to survive, there are also moments of tenderness, love, and happiness, and the body is trying to just enjoy.

“Sacrament of Bodies” is also trying to find a moment of rest in what it means to be queer in Nigeria. “The Gathering of Bastards” on the other hand was just to me trying to look at the world’s true history and trying to understand what it means to leave home, to survive outside of home, and what it means to long for a return.