The cozy room inside the Public Space One Close House provided an intimate setting for those participating in a sashiko lesson on Oct. 31.

Sashiko, the art of mending old garments in a therapeutic or holistic manner, is a long-lasting Japanese tradition that prioritizes saving everything and not wasting usable material.

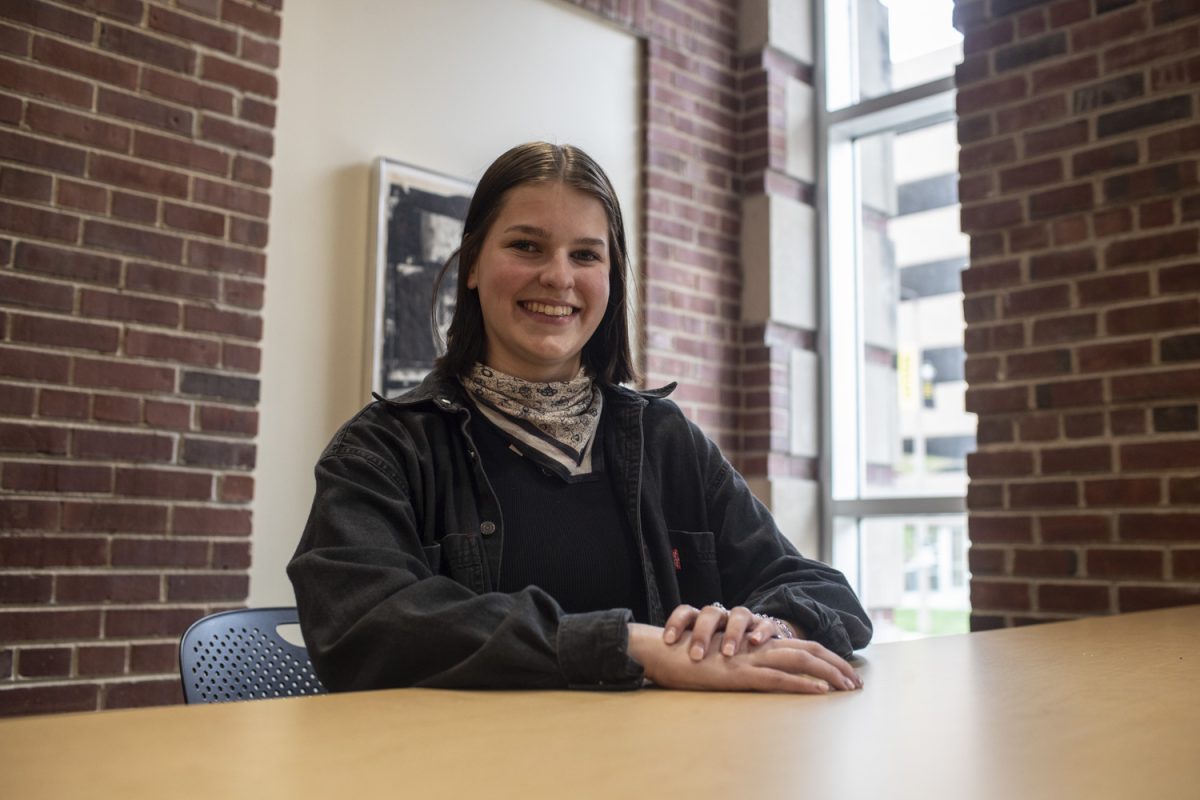

Mai Ide, a multidisciplinary artist who focuses on cultural intersectionality and ambivalence toward her identity as a Japanese woman, immigrant, and mother, led a group of around 10 participants on the ancient art form’s creation process.

Before Ide started instructing, participants already felt an intimate and close connection to others in the room. The group, some of whom were strangers to each other before the workshop, had spent a good part of the workshop sharing deeply personal stories and anecdotes, a conversation fostered by the safe and private environment that Ide established.

Though sharing stories with fellow participants was encouraged, according to Ide, the identities of each participant were to remain anonymous to respect the lesson’s involvement with personal trauma, recovery, and healing.

“You have to understand yourself before you can understand your art,” Ide said.

Ide prioritized the sentimental value that embodies the art form and spoke to the importance of self-understanding, a key insight into how personal and intentional this meditative art form is.

“Sashiko focuses on slowing down, intention, and mending both yourself and the garment,” she said. “If you are sewing in a therapeutic or purposeful way, that’s sashiko.”

Likewise, Ide places a heavy emphasis on the human body, using it as a natural starting point off which she works: abstract nipples, breasts, genitalia, and even a pair of shoes designed to look like bare feet are among her creations made with the purpose of reclaiming one’s body.

However, according to Ide, many Western brands have popularized and reduced the art form’s sentiment in the pursuit of trendiness. She also spoke of the harm and frustration this trend has caused to the traditional practice and the artists affiliated with it.

“When I moved to the United States, I realized that sashiko became just fashion and that people were teaching how to make sashiko without deeper meaning,” Ide said, choking up as she spoke. “I was shocked.”

For Ide and other artists like her, the Westernization of this cultural art form is reductive of their work as it is often mass-produced, sold for cheap and lacking any of the personal charm that is usually embedded into the work.

Apologetically breaking into tears at one point, Ide spoke about the way in which sashiko is taught in the United States. While the technique is appropriately taught, the tradition and emotional aspects of the craft are not prioritized the way in which they should be.

Most often, sashiko pieces take considerable effort and time, made to resemble strength, resilience and spirituality — something completely lost when the item is produced in a factory. Not only does it strip away the intention and passion for the art, but also the individuality, Ide said.

“An understanding of the history is often forgotten in the Western world when making sashiko,” Ide stated. “People tend to focus on only the visual aspect, which is why it’s so important that we continue to teach it properly.”

Ide highlighted the concept that sashiko is tied to spirituality just as much as it is culture, and to leave out the spiritual aspects of the art is to discard the most transcendental part of the practice.

Participants first practiced on a small hand towel that outlined a unique pattern and floral design before being given the chance to work on garments brought from home.

Attendees worked on their pieces individually, ever-so-delicately weaving while light music and the sounds of chirping birds played in the background.

The ambiance of the evening and the gracefulness of the instructor fully encompassed the passion Ide had for the art of sashiko, with participants seeming to thoroughly enjoy the learning experience and intimacy with this delicate, ancient art form.