For most artists, there is an expectation of immutability with the creation of any piece — whether on public display in a museum or simply bound to the confines of a canvas, traditional art has an indefinite shelf life.

The art of funeral preparation, however, is done with the intention that the result will only be seen once. But, for its viewers, this art form holds the utmost permanence.

“Most of our work is with the living,” Dan Ciha, a funeral director and the owner of Gay & Ciha Funeral Home in Iowa City, said. “Families are trusting us with their loved ones.”

That trust, Ciha believes, is paramount in preparation for open casket funerals. According to him, the work of any mortician not only requires extreme delicacy and precision, but a sensitivity to death.

“I never use the word ‘bodies,’” Ciha said. “‘Body,’ to me, desensitizes death.”

Despite the prevalence of death in his daily life, Ciha refuses to reduce his clients to their inanimate state.

Instead, he and his staff refer to their clients by name. By working with the loved ones of the deceased — learning about their life, interests, and hobbies — funeral directors like Ciha can develop a plan for how they will present the deceased at their funerals, the first step of which is preservation.

“The most artistic part [of the process] truly is the embalming and preparation of the deceased,” said Michael Lensing, the co-owner of Lensing Funeral and Cremation Service.

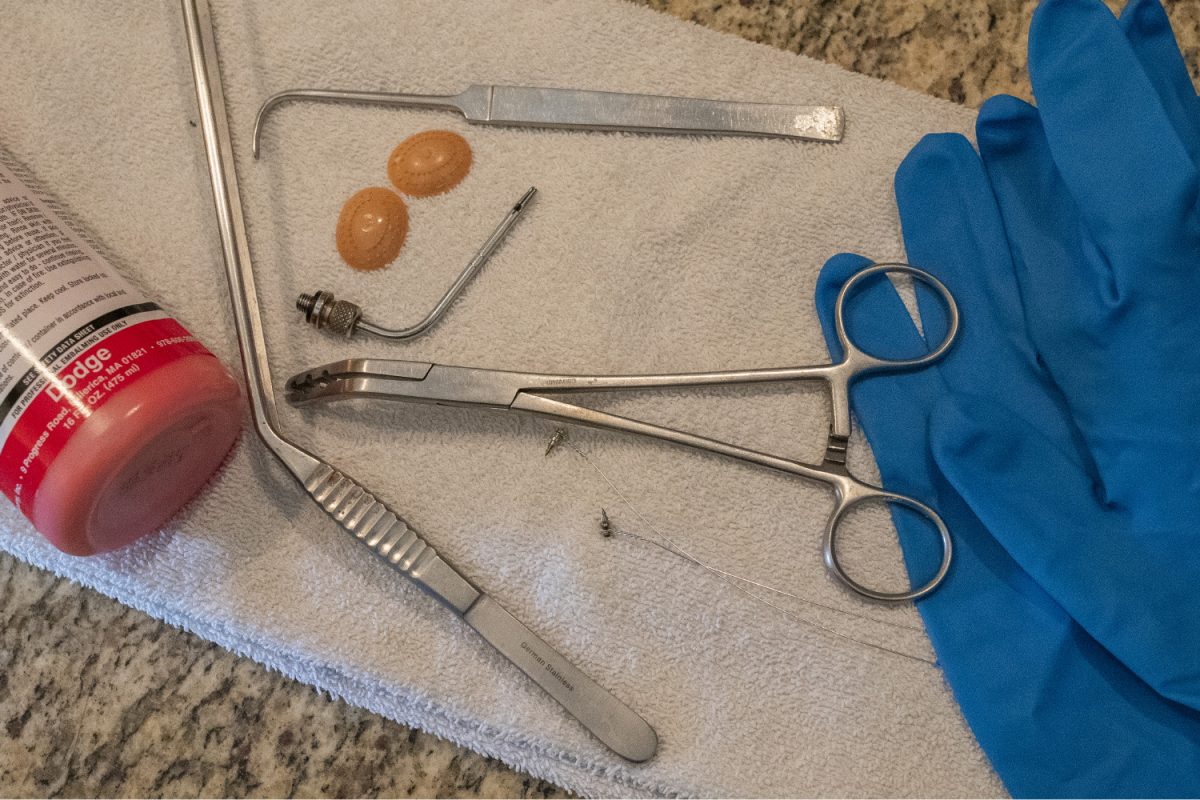

According to Lensing, to preserve a deceased person for public viewing, natural decay needs to be slowed. This is usually done through embalming, which means draining the body’s natural fluids and replacing them with embalming fluid, a preservative.

The blood’s removal from the body results in a “ghostly white” complexion, according to Ciha. Embalming fluid, however, often contains a red tint that can partially restore color to the skin and deliver a livelier appearance.

After being embalmed, the deceased person is bathed and dressed for makeup and hair.

The process is unlike traditional makeup application in many ways. Most funeral homes replace foundation with creams containing skin-colored dye matching the shade of the deceased, so the pigment is absorbed by the tissue. The same product can also act as blush.

In other ways, though, the makeup application process needs to be identical to that of a living person, with the same products — lipstick, highlighter, eyeliner, eyeshadow, and mascara.

“Families will bring pictures that we incorporate into the funeral service through a memorial folder, a video, or picture boards,” Ciha explained. “Then, I’ll look at those pictures and get a feel for what [the loved ones of the deceased] were used to seeing when they were alive.”

To the best of his ability, Ciha replicates the makeup look most often worn by the deceased, adhering to the sentiment that less is more.

“The artistry part isn’t to deny death,” Lensing said. “While you want [the deceased] to be presentable and to look like themselves, you aren’t trying to have them be remembered that way.”

Though makeup and cosmetic restoration are typically done by funeral directors and assistants, funeral homes will often enlist professional hairstylists in the preparation of a deceased person for their open casket funeral.

For Lensing, he often calls on the expertise of Molly Reynolds, a local hairstylist and owner of Mad Jac Salon.

Reynolds started working with hair 35 years ago. Before receiving her cosmetology degree and working professionally in salons, one of her first and most loyal clients was her grandmother.

“I did her hair all the time,” Reynolds recounted. “I used to curl her hair. She had been used to roller sets.”

That loyalty was mutual. When Reynolds’ grandmother passed away, she decided to style her hair one final time.

“She would haunt me if I didn’t,” Reynolds joked.

Since then, Reynolds has worked with many other deceased clients outside of her family, often on recommendation from her living clients.

“It’s an honor to send people on the way they want to look,” Reynolds shared.

Like Ciha, Reynolds typically works off pictures provided by their client’s loved ones just as a living client would provide a reference image at an appointment.

But unlike the process of styling a living person’s hair, when Reynolds and other hair stylists arrive at a funeral home, their client’s hair has already been washed and dried. To style a deceased person’s hair, they must work around the client’s supine position, curling or straightening as close to the head as possible without moving it.

However, Reynolds noted a recent decrease in the frequency of work done on deceased clientele compared to previous years, citing an increase in cremations as a cause for the decline.

“Forty years ago, most everybody was viewed in a casket,” Ciha said. “Now, they are the minority.”

His funeral home’s cremation rate has recently exceeded the casket burial rate, and he predicts that the cremation rate in Johnson County will easily reach over 80 percent in his lifetime.

Likewise, now more than half of the families Lensing works with choose cremation. To adjust for this and to continue meeting the needs of clients, both Lensing and Ciha have added in-house crematories to their respective funeral homes within the past two decades.

Lensing explained that the growing preference for cremation and the deviation from traditional burials in the U.S. could be the result of many things. Cultural practices and financial limitations are among the biggest reasons, but Lensing also feels the shift is in the reactions to seeing death itself.

“For most people, the hardest part of death is the stillness,” Lensing said. “But that’s also what’s peaceful about it.”

In the case of a traumatic death or visible injury, more work is required to restore the deceased to a state that is considered presentable for open casket viewing. This process is called restorative art.

“I could rebuild an ear just by measuring with my fingers,” Ciha said, explaining that the length of one’s nose from the top of the bridge to the septum is often the same length as their ear — one of the many techniques he learned while attending the Dallas Institute of Mortuary Science.

Unfortunately, there are cases in which the visible damage, whether because of its severity or location on the body, is unable to be restored for viewing. Lensing recounted an experience he had early on in his career with one client, a young woman, who was the victim of a fatal car accident. The brunt of her injuries was facial.

Because of this, Lensing kept the young woman’s face covered upon visitation from her parents. The wounds were traumatic, he shared, but her parents insisted on an open casket service.

Lensing recounted feeling at a crossroads. Though her injuries were beyond restoration, Lensing was determined to give the family the burial they desired. So, he got creative.

“She played tennis in high school, and whenever she played, she would pull her hair back and use a blue bandana,” he said.

Lensing used this bandana to partially cover her face. Her hands and wrists, decorated with her tennis sweatbands, were positioned to hold a tulip bouquet that covered the remainder of her face.

“I had done as much as I could, but the kids her age — they knew that was her,” Lensing said.

He believes that the goal of funeral preparation is never to mimic life, but to establish comfort with death.

“Sometimes it’s just about being in the presence of the body, which can be artistry in itself,” Lensing said. “What people really want is to celebrate a life.”