UI Plasma Wave Science instrument spends 45 years in space

NASA’s two Voyager spacecrafts, originally intended to just pass the planets Jupiter and Saturn, are being recognized after 45 years of space exploration. The Plasma Wave Science instrument, created by UI scientists, remains an integral part of the spacecraft.

September 7, 2022

University of Iowa scientists helped create instruments for the Voyager, Nasa’s longest mission, in 1977, marking 45 years of space science.

When the project started in the 1970s, UI research scientists contributed the Plasma Wave Science instrument for both Voyager 1 and 2, which measure naturally occurring plasma in outer space.

William Kurth, a research scientist in the UI department of physics and astronomy, is the third principal investigator for the Voyager Plasma Wave Science team, which was established in the 1970s.

“I don’t think anybody realized the Voyagers would go on for this long,” Kurth said. “They have a warranty so to speak of four years, which is how long it would take them to get past Jupiter and Saturn. They are eleven times passed that period of performance.”

RELATED: UI graduate Jack Sieleman scores job at NASA

According to NASA, the first Voyager mission was originally created for the U.S. to explore Jupiter and Saturn. After the spacecraft made discoveries, such as active volcanoes, Voyager 2 was born.

Both spacecrafts are still sending information back to Earth from interstellar space and are exploring the solar system.

The first spacecraft was launched on Aug. 20, 1977, while the second was launched on Sept. 5, 1977.

Kurth came to the UI in 1969 and has worked with the Voyager mission ever since. As a graduate student, Kurth said he worked on the plasma instrument on both Voyagers, where he helped to test and calibrate them.

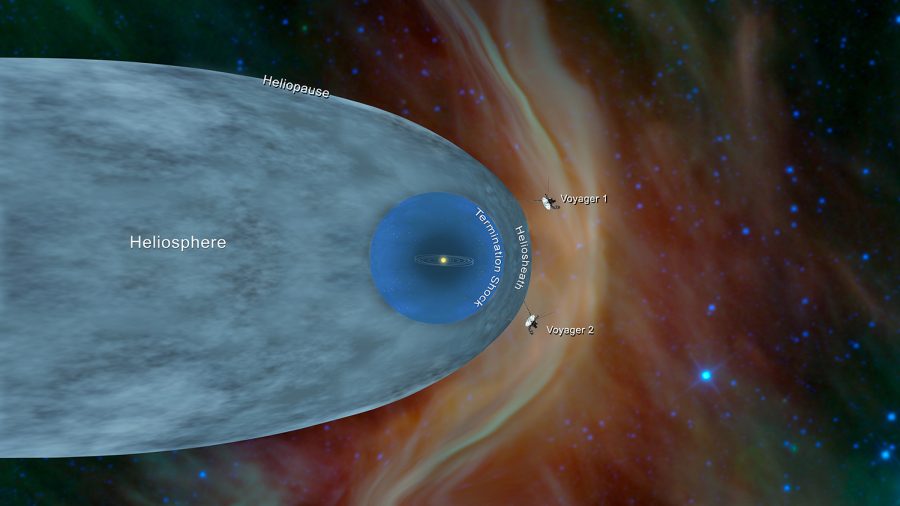

Both Voyager missions measure the density of the interstellar medium just beyond the heliopause, the plasma boundary of the solar system, he said.

“The original goal expanded from Jupiter and Saturn, to Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune,” Kurth said.

Kurth said Voyager 1 is beyond three quarters of a light day from Earth. It takes 22 hours for a radio signal to be sent from Voyager 1 to Earth, he said.

“We launched two spacecrafts, and if one of them fails we still have a chance of success with the mission. We were very lucky in that both spacecrafts have survived for 45 years now,” he said.

He said the survival has provided the opportunity to send spacecraft in different directions into the interstellar medium.

For Kruth, being appointed to work on the Iowa instrument back in the 1970s resulted in creating history and years of happiness.

“I had no idea the breadth of discoveries that they would make, or the length of the mission, or the groundbreaking explorations that they would carry out,” he said.

Larry Granroth, a systems architect at the UI, also worked with the Voyager mission and entered data during the summer of 1979.

Granroth has worked as a full-time UI staff member for 40 years. He started working on the project digitizing observations of whistlers from Jupiter.

“What this means is that there were lightning discharges on Jupiter that produce these signals,” he said.

Additionally, Granroth took over a public outreach project from UI professor and scientist Donald Gurnett. Gurnett served as a principal investigator for the Voyager Plasma Wave Science team and also helped create the plasma wave instrument.

The project was to create a public domain in the 1990s to share space audio with the public, he said.

“One of the first things that we did was make the audio recordings from a lot of these missions available to the public,” Ganroth said. “It’s the only mission that’s been to all the outer planets and now into interstellar space,” he said.

For Ganroth, the mission has even resulted in scientists knowing more about the world than they ever expected.

“What’s the purpose of humankind if not to understand more of our environment, to learn more about the universe,” he said.