Ukrainian UI professor, student reflect on media use during wartime

Two Ukrainian University of Iowa community members say restricted media and misinformation can impact people’s understanding of the Ukrainian-Russian conflict.

Richard Yu holds a flag at a vigil for Ukraine outside of The Pentacrest in Iowa City on Sunday, April 3, 2022.

April 3, 2022

Ukrainian members of the University of Iowa community are reflecting on their experiences with propaganda and misinformation during wartime as the conflict between Ukraine and Russia continues.

As of March 29, Russian forces began to retreat out of Kyiv in part of a “major strategy shift.” The United Nations Office of High Commissioner for Human Rights reported on the same day 3,039 civilian casualties in the country, with 1,179 killed and 1,860 injured.

Daria Kuznetsova, a UI doctoral student in political science from the Donbas region of Ukraine, said her research focuses on digital media and information communication technologies, and their effect on protests and regime change.

She became interested in the topic after taking a course on the subject and reading articles published about using media technology as a weapon during wartime.

Some instances include the 2020 Belarus protests and Russian protests from 2011 to 2013, when Moscow, Russia’s capital city, saw the largest anti-government rally since the fall of the Soviet Union.

“People in Ukraine are aware of the scale of Russian propaganda, and it’s not that easy anymore to make people believe in the messages that are seen on some social media, or just the internet,” she said.

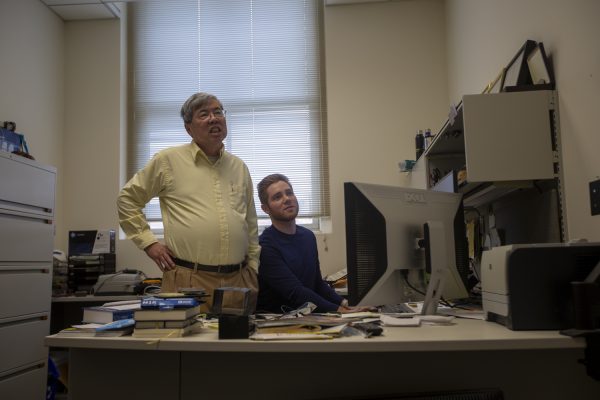

Sujatha Sosale, UI associate professor of journalism and mass communication, has taught several courses in communication and change and in social media. Sosale said what is occurring in Ukraine and Russia are examples of misinformation and disinformation.

Misinformation, Sosale said, is something misleading but not necessarily with an intent to do so, while disinformation is with an intent to mislead, such as propaganda.

“The information war, in some senses, is really about the war to shape public opinion and get public opinion to support one side or another,” Sosale said.

Kuznetsova said most Russian media is not free; it is either state-owned or owned by Russian tycoons with close ties to the government. She said that before 2011, the internet was an alternative source of information for people looking for independent press.

“Since then, the government recognized the potential of the internet to connect people, overcome the collective action problem, go on the streets,” she said. “Somewhere starting around 2012, we saw the Russian government consolidating the ownership of internet infrastructure, internet companies.”

She added that the absence of opposition leaders and media can negatively affect those who are on the ground. She said reporters who try to show Russians footage from Ukraine are met with fearful looks.

“A lot of people just say, ‘I’m for Putin’ and they pretty much ran away from the camera,” Kuznetsova said. “You can clearly tell that people are scared.”

For UI professor Marina Zaloznaya, her own identity complicates how she processes the conflict. Born and raised in Crimea, she said she has loved ones in both Russia and Ukraine, so she is concerned for all of their well-being.

Zaloznaya was the original organizer of the demonstration of peace rally held on the Pentacrest on Feb. 27. She said she was harassed for having both Russian and Ukrainian citizenship and told that she was “on the other side.”

“There is definitely absolutely no question who the aggressor is and who is at fault for this unfolding tragedy — it’s Russia,” she said.

Despite being angry and sad at the comments she received, she decided it was best for her to withdraw her participation to protect her family.

RELATED: Demonstration for Peace gathers on Pentacrest as conflict continues in Ukraine

She said seeing everyone come together during that rally without an organizer to lead them was incredibly powerful.

“Ukrainians in Ukraine really amaze the world with the strength of their attachment to democracy, to freedom, the ability to express their political opinions openly,” she said. “And I think that the Ukrainian community here in Iowa City is showing just that, as well.”

She said the Russian government does not represent the opinions and beliefs of a lot of Russian citizens, and that many are against the bloodshed.

Zaloznaya’s family and friends are primarily in Kyiv, she said, and have been able to communicate through social media. The connection is not reliable, she said, because her family, like many, must seek shelter in the basement of their residential buildings during bomb raids with limited internet access.

She added it is increasingly difficult to get objective information from the media, particularly in Russia.

“The state-curated propaganda that they see on TV, and official news sources in Russia are underplaying the conflict, not reporting on the extent of civilian casualties and are not fairly representing the suffering that they’re inflicting,” Zaloznaya said.

She said she would go so far as to say information is not being misconstrued — as it is blatant lies.

“The government has basically cut off all of the channels for anybody who wanted to represent the opposing point of view,” she said.

Ekho Moskvy (Echo of Moscow), one of Russia’s independent radio stations, was forced to shut down on March 3 after the Russian government took them off the air on March 1.

On March 14, main Russian station Channel One employee Marina Ovsyannikova was detained after going on air with a sign saying, “No War. Don’t believe propaganda. They’re lying to you here.”

“It’s a total crackdown on freedom of speech,” Kuznetsova said.

Zaloznaya said the recent Ukrainian-Russian conflict is an information war, more than any other war in the two countries’ history.

“It’s fascinating to watch how the traditional warfare — boots on the ground, airstrikes — combines with this new way of waging war by controlling what it is that people hear,” she said.

Sosale said information that goes out to the media is very important in shaping the way people view the conflict.

She said the U.S. media expressing pro-Ukrainian sentiments, such as highlighting Ukrainian wins over the Russian military, helps promote support during wartime, particularly in cases of potential direct intervention and participation from other countries.

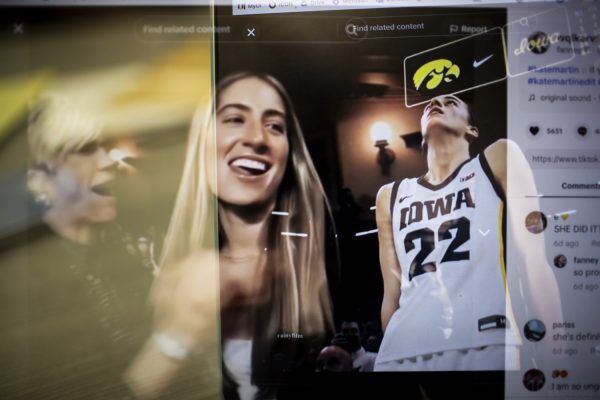

Sosale added that most of the younger generation receives information almost entirely from social media instead of going to professional news outlets.

“Social media during wartime is like social media at any other time: partial information, exaggeration, fake news, trolling,” she said. “It’s not the entire picture.”

However, even accessing the internet has proven to be difficult. The New York Times reported on March 24 that Russia is blocked from the internet after the country put up a “digital barricade” between itself and the international community.

Zaloznaya said the internet has served as an important platform for anti-government mobilization in Russia.

“People connect through various platforms online and organize to go out to the streets or take to the streets to show their unhappiness and disgruntlement with that with the government,” she said. “And, now that that’s being sort of limited, it’s also contributing to this terrible situation.”