UI researchers to develop lead detection tool for water

Researchers from the University of Iowa are looking to aggregate data and develop an algorithm for communities to identify their individual risk of lead exposure in their drinking water.

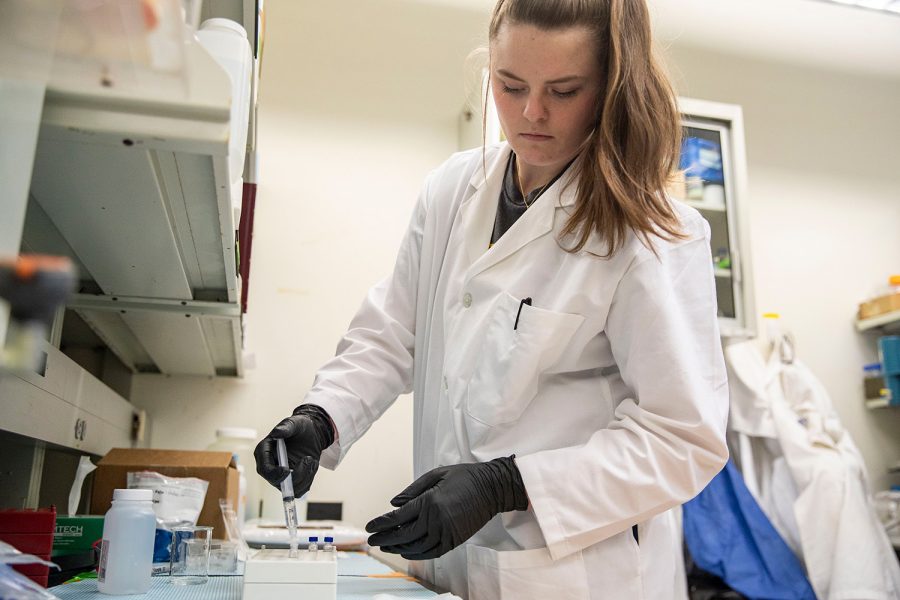

Graduate Research Assistant in the department of civil and environmental engineering Danielle Land filters a water sample in the Seamans Center on Tuesday, March 29, 2022. Land is part of a group that is developing an online tool that identifies which homes might be at risk of water contamination from lead.

March 29, 2022

Researchers at the University of Iowa are developing a system for residents and public health officials that will allow them to more easily detect lead in drinking water across the state.

The research involves collecting data and developing an algorithm to predict where individuals are most at risk for lead exposure in their communities and the resulting ailments.

David Cwiertny, principal investigator for the study and UI professor of civil environmental engineering, said he and his team hope to create a system to prevent the negative health effects that can occur from ingesting lead. While the team has been broadly researching lead contamination in water for four years, the research for the system has been going on for two years.

Consumption of water from tainted sources is especially bad for young children, Cwiertny said, because much of their body is still developing.

“It’s a neurotoxin,” Cwiertny said. “Children are most vulnerable because their brains are still developing, their central nervous systems are still developing. Also, they have a higher rate of metabolism and so there’s a greater chance that the lead can be accumulated.”

Many of the highest risk children are often bottle-fed, he said, and formula is the lone source of nutrition for these children, which can be bad because it is made by mixing with the lead water.

Cwiertny said contamination often comes from outdated infrastructure, including lead pipes used in older water lines. His and his team’s research will look at other potential contamination sources, including soil.

RELATED: Iowa City sees water mains break from aging infrastructure

“Lead is one of these things that still plagues far too many communities today,” Cwiertny said. “We also know that the impacts last a lifetime. It is pretty well established that exposures to lead as children leads to lost IQ, which leads to lost income over the lifetime of these individuals.”

He said his team is very passionate about environmental issues and social justice, and their research strikes at the heart of these issues.

“There is a justice issue here,” Cwiertny said. “It tends to be lower-income communities of color that are more vulnerable to lead in drinking water and lead exposures around the home and at the workplace.”

Danielle Land, a civil environmental engineering graduate student and research assistant with the IIHR-Hydroscience and Engineering, said she is passionate about solving the issue of lead contamination in water because she saw the effect it can have on a community firsthand in Flint, Michigan.

Land studied the effects of lead-tainted water in Flint with Mona Hanna-Attisha, the pediatrician who in Spring 2020 linked high levels of lead in patients’ blood to their drinking water in Flint.

“It’s an environmental justice issue,” she said. “If you are Black, you are significantly more likely to have more lead in your blood. It is actually wild when you look at the breakdown and disparity in lead exposure.”

A study published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health concluded there was a “significant nationwide racial disparity” in the U.S. for predominantly Black children and revealed Black children had 2.8 times higher odds of having elevated blood lead levels.

Land said addressing the health effects of water tainted with lead is so important because of the long-term effects it can have on individuals.

“It’s more than just, ‘Our water is being polluted,’” Land said. “The health effects of lead are profound and there’s nothing you can really do about it once you’re exposed to lead … The residents of Flint, they won’t drink their water. It’s a trust issue. The government and every level of administration had failed them.”

Lan said she hopes the research hopes put the power to detect lead back in the hands of homeowners and begin to create an algorithm for residents to assess their risk factors for lead contamination in their water.

The algorithm will be trained by data collected in Iowa and by Hanna-Attisha’s team in Flint, and Land said she hopes the research can go as far as to help change environmental regulations.

Drew Latta, assistant research scientist in the UI College of Engineering, said his role on the research is to drive the methods being used in this research and take measurements of lead concentrations.

The project began in 2018 as the result of water contamination in Kalona, Iowa, he said. The algorithm resulting from this research will help predict where water testing efforts would best be served.

“I think my hope is that we can use some of this data and make some sort of prediction of where we should focus our efforts,” Latta said. “Which homes do we focus on, which people are at the most risk? That also might be folks that can’t afford to buy a filter or afford a filter or drink bottled water.”

Latta said the goal of the research is to intervene as early as possible and reach zero lead exposure in the water.

Cwiertny said while he believes the work will be difficult, he hopes to develop and train the tool using data such as the age of the home and ultimately prevent as much harm as possible.

“Our aspirations are that we develop a useful tool and that it’s a tool that doesn’t just help one community but can be generalized across multiple communities,” Cwiertny said. “[We hope] that public health practitioners will use that tool to intervene sooner.”