UI professor publishes book about his role in researching, publicizing toxic-shock syndrome

University of Iowa professor Patrick Schlievert’s book, “What was I Thinking? Toxic Shock Syndrome” discusses his research on toxic shock syndrome.

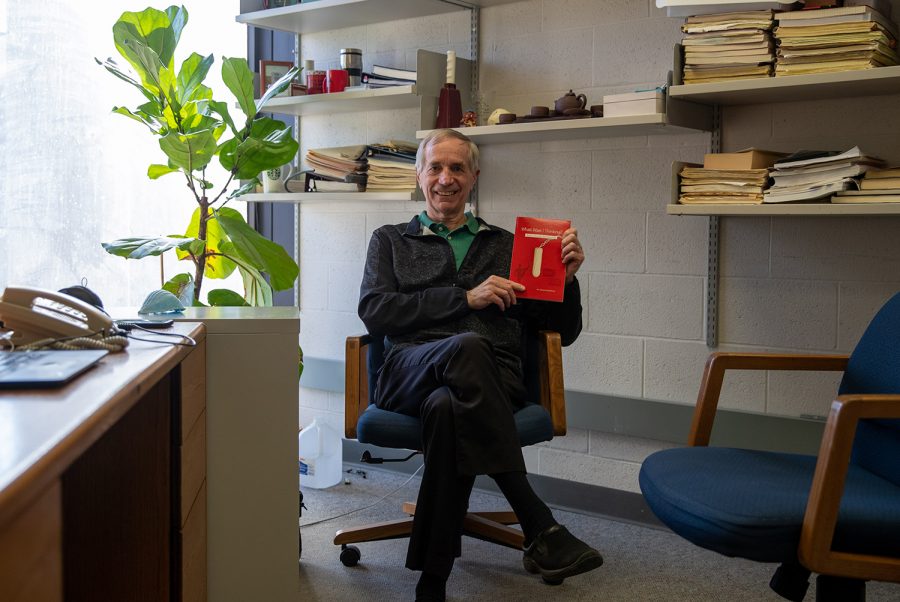

Professor Patrick Schlievert displays his new book “What Was I Thinking?” on Monday, March 1, 2021. Schlievert said he wants to make his research known to the people. “The American public to me is who I do my research for. Period,” he said.

March 7, 2021

Toxic shock syndrome made its way to the public eye in 1980, helped by what University of Iowa Professor Patrick Schlievert calls a “media blitz,” when he called news outlets with information on the syndrome. At the time it wasn’t recognized by national health organizations.

Schlievert accepted a faculty position at the University of California-Los Angeles in 1979 when he began studying different toxins, eventually finding toxin-1, the principal cause of toxic shock syndrome.

The now-professor of microbiology at the UI has recently released a book chronicling his experience in researching, publicizing, and pushing for regulation with the condition called “What Was I Thinking? Toxic Shock Syndrome.”

“This is why I publicized [toxic shock syndrome] — so every woman would know what the symptoms were and what to ask their physician,” Schlievert said.

According to the Mayo Clinic, toxic shock syndrome is a bacterial infection. While it can occur in anyone despite age or gender, about half of the cases occur solely in menstruating women amid their use of tampons and other devices such as menstruation cups. Symptoms include diarrhea, fever, rash, confusion, and seizures.

Schlievert studied the strange reports of illnesses in women occurring across the country as a professor and researcher. The condition wasn’t tracked by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of Health, or the Food and Drug Administration in 1980, so he took his case to the media. In 1980, the condition rose in public prominence when 814 women developed what became known as toxic shock syndrome, and 38 died from it.

Schlievert found himself on national news and several radio and TV stations across the country. Toxic shock syndrome soon became the second biggest news event at the time, he said, after the Iran Hostage Crisis.

“But they (health organizations) weren’t even interested in it back then, and so I thought that was really inappropriate,” Schlievert said. “So, I just continued doing my thing, talking to all the national news media, everybody.”

One tampon, Rely, was removed from the market after federal officials identified it as a primary cause of toxic shock syndrome.

Schlievert’s confrontations with the CDC and NIH didn’t end there. The NIH said it had no interest in the disease and refused funding to him.

But Schlievert’s research continued, and Schlievert found that high absorbency tampons released a large amount of oxygen and air into the vagina, a typically anaerobic part of the body, which are key ingredients in producing toxic shock syndrome.

“In 1984, I finally got all of the highest absorbency tampons off the market because of a Kansas City court case called Ogilvy versus International Playtex,” Schlievert said.

RELATED: College of Public Health examines mental health challenges for farmers

In his research published in the early 2000s, Schlievert found that for every 100,000 women who use tampons, three to four would develop toxic shock syndrome in a year. But if caught early, toxic shock syndrome can be treated.

Women’s health has historically been underfunded and under researched, according to The Guardian. The NIH did not require women to be included in medical studies until 1993. According to the Society for Women’s Health Research, the default body is still a male body.

Wilmara Salgado Pabón is an assistant professor of microbiology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. From 2011 to 2019, she worked at the UI with Schlievert as a research advisor and later as chair of the department when she became an assistant professor.

Salgado Pabón also studied toxic shock syndrome, looking into infective endocarditis and how it affected the disease. She said that when she worked at the UI, Schlievert used to share his stories about his time researching toxic shock syndrome.

“You talk to people about how big of a deal it was back in the 80s to really get the story straight, to save women pretty much from this,” she said. “Back then there were no guidelines on absorbency. There were — there are still, actually — all sorts of misunderstandings about what caused the disease.”

Lilliana Radoshevich is an assistant professor of microbiology and immunology at the UI. Schlievert recruited Radoshevich from the Pasteur Institute in Paris.

Radoshevich said that Schlievert was a mentor to her, and they worked on similar pathogens. She said he would be much more recognized if his projects weren’t so controversial at the time.

“I think he’s quite a fierce advocate for Iowans and for first-generation students as well,” Radoshevich said.