University of Iowa researchers discovered ‘chemical earmuffs’ that could prevent hearing damage

University of Iowa researchers in the Biology Department recently discovered a compound that could block possible channels in the ear to prevent hearing damage without halting audio transmissions to the brain.

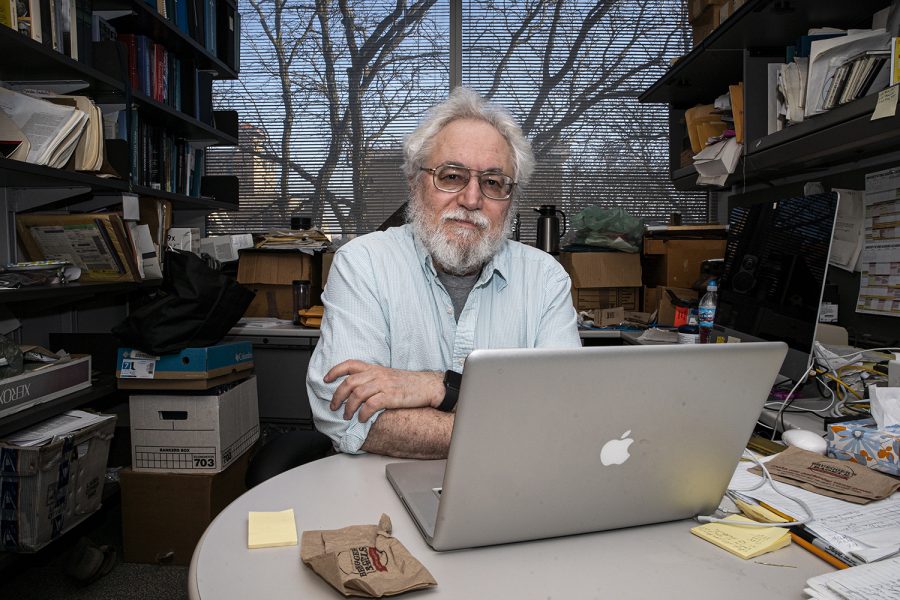

University of Iowa professor Steven Green poses for a portrait in the University of Iowa Biology Building on Monday. Professor Green and Associate Professor Ning Hu of the UI Department of Biology recently discovered a receptor that can prevent a common type of hearing loss by testing it on mice, sparking the discussion of finding more drugs that could prevent hearing loss and distributed non-invasively.

February 11, 2020

While traditional earmuffs may keep human ears warm in the cold months, researchers have recently created “chemical earmuffs” that are currently being injected into mice ears to protect against permeant damage to the ear.

Biology Professor Steven Green and Associate Research Scientist Ning Hu found a way to close off certain receptors in the ear to prevent hearing damage while also allowing audio information to be transmitted to the brain, discovered by injecting a compound into the ears of mice.

In previous studies, it had been determined that blocking all channels could prevent damage but would halt any hearing, he said, so this research was conducted with the hopes of allowing mice to still hear while protecting their ears.

“Our number-one hurdle now in application is to find out if the compound could be delivered to humans orally or by injection, something much more practical than injecting straight into the ear,” Green said.

The compound affects the meeting point of the hair cells and nerve cells, called the synapse. All of these components assist in sending sound to the brain, forming receptor channels.

Green said they found a mix of differing receptor channels and could prevent hearing damage by identifying the ones that cause harm to the ear, but emphasized that while this worked in animal test subjects, it was not ready to be administered to humans.

“We want to make sure not only that the compound can be administered in a way that’s effective, but also that it is safe,” he said.

Hu emphasized that many people do not take hearing damage as seriously as they should, especially when students listen to music too loudly.

“In society, you are exposed to a lot of noise,” he said. “Whether you are going into a bar, or at a party, or even wearing headphones, noise damage can happen.”

Cells in the brain area, including nerve and sensory cells, are unable to repair themselves, Green said. Throughout human evolution, there was never noise loud enough to cause the damage that can be done today, such as the use of firearms in battle by soldiers, he said.

RELATED: Team co-led by UI biologists discover gene key to human hearing

Green said providing this potential receptor blocking in humans would be geared toward job-related situations, such as the military. He said hearing impairment is one of the major complaints among veterans, so having this be accessible to humans would make significant change.

The potential for chemical earmuffs could also be used for loud events on college campuses, such as concerts and football games.

“At football games, fans are encouraged to make a lot of loud noise,” Green said. “From the numbers I have seen, and the noise in these cases is enough cause permanent, irreversible damage to the ear. It’s incredibly irresponsible to be encouraging that, and it’s terrible for the people who work there.”

Moving forward, if the compound was available for human use, the Biology Department would reach out to the UI audiology program as a potential partner, he said.

The UI is ranked second in the U.S. for its graduate audiology program under Vanderbilt University by U.S. News and World Report.

UI Biology Department Chair Diane Slusarski said the research that Green and Hu conducted took a significant step in the direction of preventing hearing damage.

“People don’t realize that when things are loud, it accumulates over time, and you will sustain damage,” Slusarski said. “This is a very large societal problem. We know there is damage, so what we need to know is ‘how is it happening, and how can we fix it?’ Hu and Green are making progress on answering this question.”