Board of Regents hears annual student financial aid report

At a state Board of Regents meeting in Urbandale on Wednesday, financial aid directors from the three regents’ public universities presented their annual financial aid report.

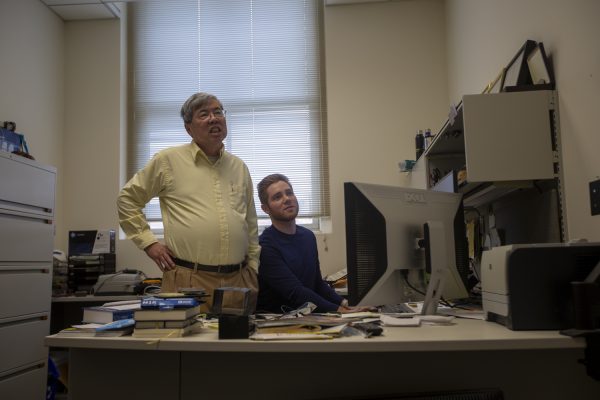

The Office of Financial Aid is seen inside Calvin Hall on Tuesday, Dec. 10, 2019.

February 5, 2020

URBANDALE — Heads of financial aid from the state Board of Regents institutions addressed accessibility to and affordability of college for students, as well as their efforts to minimize debt in the face of increasing costs, at the regents’ Wednesday meeting.

Regent institutions use financial aid as a mechanism for recruitment and retention, said Roberta Johnson, director of the Financial Aid Office at Iowa State University. Alongside financial aid heads Cindy Seyfer from the University of Iowa and Tim Bakula from the University of Northern Iowa, Johnson said the trio is working to stabilize student debt.

“We don’t want to just bring students to our institutions only to have them find out later that they cannot afford to stay,” Johnson said.

One way to close financial gap for college costs is to make students and their families more aware, Seyfer said. That means not packaging the Parent PLUS Loan, she said. All three regent universities have already, or are planning to, stop packaging the loan in an effort to make sure parents know the loan is credit-based and not guaranteed.

RELATED: Iowa regent universities using financial aid to offset rising tuition

By not packaging the PLUS loan, Seyfer continued, parents won’t arrive on campus thinking that finances are covered and then be unable to access it.

“It doesn’t mean that we’re not telling students and parents about that resource and that they’re not able to take advantage of that,” Seyfer said. “… We want to make sure that families are exploring all their options and are fully aware of what they’re going to need in terms of covering their costs.”

To see student debt drop dramatically is an unrealistic endeavor, she said, so for now, staying stable is a “win.” A number of goals motivate how each institution awards financial aid, Johnson added, and often those goals seem to contradict one another — like affordability and accessibility.

“We’re doing an interesting mosaic … to put together the best package to encourage students to enroll at our institutions,” Johnson said.

Approximately 69 percent of UNI students, 58.5 percent at ISU, and 50 percent at the UI borrow to fund their education, Bakula said, adding that the regents mandate financial literacy training for students.

Compared with to peer institutions in the U.S., Johnson said that regent institutions are relying more heavily upon institutional funding. According to data she shared from 2018-2019, 6.6 percent of undergraduate financial aid in the U.S. was provided by state grants, compared with 0.4 percent in Iowa.

At public institutions, federal financial-aid dollars equal $373.1 million, regents’ dollars another $273.3 million, the state awards $2.8 million, and $122.3 million from outside organizations and foundations — scholarships which many students, particularly freshman, are acquiring when they enter college, Johnson said.

RELATED: Board of Regents discusses student financial aid, debt

“… In many of the other states there are robust state grant programs that are available to assist students at those institutions,” Johnson said. “So, we are relying very heavily upon institutional aid to assist us, as well as using the federal programs and the funds that our foundations are raising.”

The decrease in state funding for financial aid between the 2008-09 academic year and the 2018-19 academic year has totaled 60 percent, Seyfer said. Unfortunately, she added, there have been very minor increases in federal aid in the last 10 years.

The UI discontinued a Summer Hawk Grant program, which provided financial assistance to in-state students taking classes in the summer with a goal of helping students not on track to graduate in a timely manner, after the 2017-18 academic year. Seyfer cited less-than-expected rises in four-year graduation rates and dwindling state funds as the reason for the grant ending.

Fifty-four percent of the Class of 2017 graduated in four years, matching the four-year graduation rate of the prior two graduating classes.

Another consideration that financial aid offices at each regent institution have made over the last few years, Seyfer said, is the basic needs and often unexpected costs that students face — homelessness, food insecurity, rent, and more. Meeting these needs often takes the form of emergency grants, she added.

“Ways in which we help people that may not have an actual monetary value attached to it may not show up on these reports,” Seyfer said, “but are really important to the retention and the well-being of our students.”