UI researchers use 3D technology to scan French cathedrals

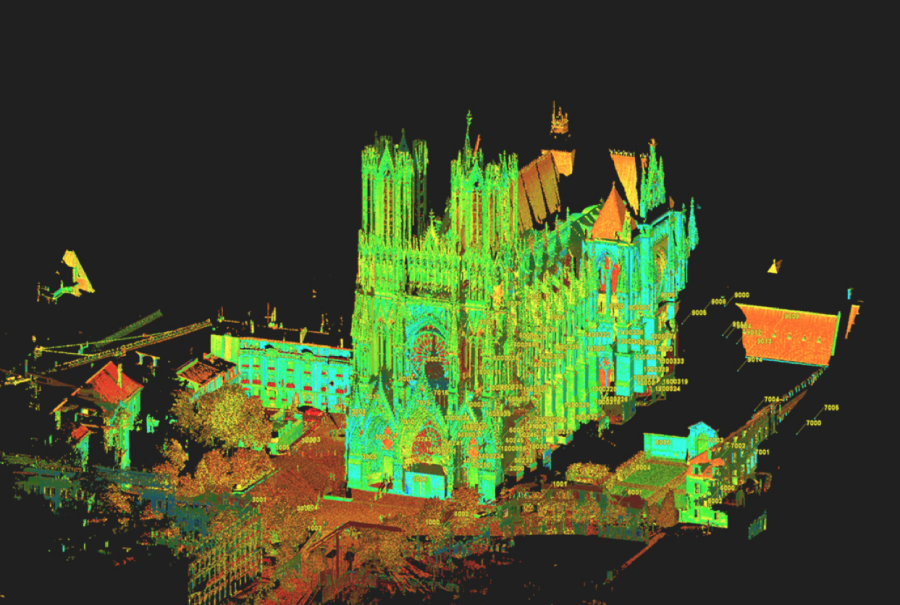

Through the use of Light Detection and Ranging technology, professors and students created three dimensional images of cathedrals in France.

April 25, 2019

After visiting the Reim Cathedral, the coronation site for French kings until the 900s, and living in France as a child, University of Iowa art history Professor Robert Bork became interested in Gothic architecture and how a society without modern technology could build complex structures.

Last summer, Bork, two other UI professors, a graduate student, and an undergraduate student traveled to France to scan cathedrals using light detection and ranging technology.

While in France, the researchers used LiDAR to scan both the interior and exterior of the Metz and Reim cathedrals in a few days. They were able to use one scanner inside the building and one outside to collect images simultaneously, and they are now working to piece the scans together, Bork said.

To scan the buildings, the researchers put up targets around the interior and exterior as points for the scanners to focus on, said Adam Skibbe, a Geographical & Sustainability GIS administrator and researcher. The scanner projects a laser onto the building at the speed of light; the time between when the laser hits the object and bounces back is how the three-dimensional image is created, he said.

Some of the cathedrals in Europe have drawings depicting the planned design of the structure, but not many do, Bork said. Using LiDAR creates a picture of the plan that researchers wouldn’t otherwise have, he said.

“For me, most of my scholarship is about geometry and design,” Bork said. “So, I want to know what the thing would have looked like in the mind’s eye of the designer. The fact you can have a three-dimensional model, you can cut and slice it, and see the ground plan and elevations, and see what the designers had in mind.”

Along with scanning the cathedrals, LiDAR has been used to scan landmarks in Iowa City and surrounding areas, including Kinnick, the Pentacrest, a meteorite the university has, the beer caves, and the house of Herbert Hoover, Skibbe said.

He teaches people to use the technology, allowing students to have hands-on experience using equipment they might not otherwise have a chance to use, he said. The students in the class use the equipment to scan objects as well as learn how to put the scans together to create the three-dimensional image they want, he said.

“We’re lucky we have [the scanners], but a lot of private and public companies are going to picking these things up and using them,” Skibbe said. “It gives [students] that hands-on, start-to-finish, real-world experience.”

Beginning early on in his time at the UI, graduate student Drew Hutchinson had the opportunity to use LiDAR to scan different objects, including the Tilden Meteorite housed at the UI, he said.

The experience of traveling to France with Skibbe and Bork gave Hutchinson the opportunity to map one of the cathedrals by himself, and he has worked on creating the 3D model, he said.

“Using [the scanner] outside the university context just wouldn’t even be an option for most people,” Hutchinson said. “That’s definitely one of the benefits of being at the university.”