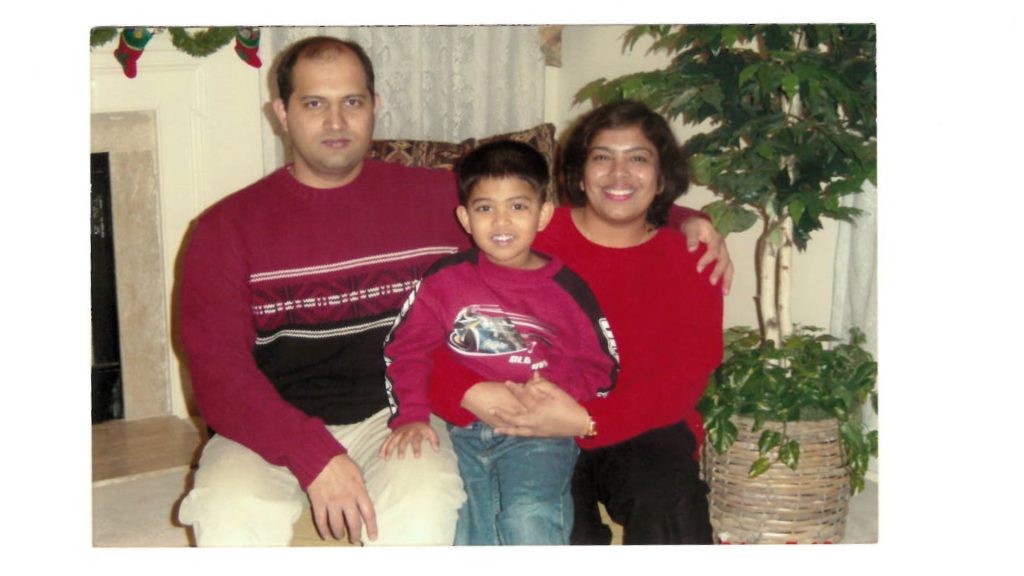

My mother is a strong believer in the institution of joint families. I grew up listening to stories from her about how eventful her childhood was growing up with all her cousins, aunts, and uncles. She grew up surrounded by her extended family, with all living under one roof.

In fact, her family was so close knit that for the longest time my mother identified 12 of her cousins as her siblings, though she has only one real brother.

She keeps telling me the experiences I am missing out on by living in a nuclear family with just me and my parents.

Typically, a patrilineal extended family in India consists of a married couple, their sons, and their families. Traditionally, daughters live with their parents until they get married; then, they move in with their husbands’ families.

The custom of living in joint families has been around in India since 500 B.C.E.

Traditionally, the family owns a business, which is run by the male members of the household, while the women take care of the house.

According to an article published by the University of Columbia’s Pacific Affairs, the income earned is shared by everyone living in the household to meet their needs.

RELATED: Tambe: The thin lines among education, faith, and superstitions

Living in extended families has its advantages. Household chores are divided among members and thus become easier; responsibilities in the household are shared, and everyone in the household helps raise children.

This arrangement, many say, fosters learning among children and makes them realize the importance and value of relationships. Children learn values such as sharing and contributing to the household. The elders in the house teach children about religion, age-old customs, and traditions.

It is difficult for children growing up in nuclear families to learn these values and lessons. Parents have to go an extra mile to play the role that was traditionally played by the children’s grandparents and teach their children about religion.

However, India has seen a decline in joint extended families since the 1980s. As a result of modernization, the younger generation of Indians started migrating from their hometowns to big urban centers that offered lucrative jobs.

Research published by Princeton University suggests joint families in India declined in rural parts of the country possibly because of the adoption of urban culture in rural parts. By the 1990s, it became common for children to get married and then move out of their parents’ houses.

RELATED: Tambe: India’s faith in arranged marriages

According to a report from India’s Ministry of Internal Affairs, although joint households are on the decline, they are still the dominant system of family.

Unlike in the United States, young Indian adults typically return home after completing college and either continue living with their parents or move out to start a family of their own.

In fact, according to India Today, 74 percent of India’s youth still prefer living in joint families.

Being raised in a nuclear family, however, it seems impossible for me to live in an extended family.

Whenever my mother narrated her stories to me, I wondered, how could so many people live together in one house without any personal space?

As I was growing up in a nuclear family, my parents did face problems that would not have come up a traditional joint family.

For as long as I can recall, both my parents worked. They continually worried about sending me to a daycare or finding someone to baby-sit me. They had to multitask between looking after the house and going to work.

Such problems typically do not arise in joint families.

RELATED: Tambe: Fairness creams and the desire to be different

My mother long told me about her older cousins helping her with her schoolwork and the elders in the house teaching her about culture and religious traditions. She was seldom bored; there was always someone at home to talk to or play with.

Looking back after attending college in the United States for two years, living in a nuclear family has had several advantages. We were able to live our lives independently. We were free to make our own decisions as a family. We had our own personal space. Most importantly, I always had the undivided attention of my parents.

Although the concept of living in extended families is not as commonly seen in the United States, with changing demographics, it is gaining popularity.

According to a report published by the Center for American Progress, the U.S. population living in extended families increased from 58 million in 2001 to 85 million in 2014.

Extended families are formed in the United States as many immigrants come from cultural backgrounds in which sharing home is the norm, the report states. As of 2014, extended families represented 17 percent of all households.

In traditional Indian joint families, the elders would usually decide the profession of the children in the family, at their birth. It was the children’s job to struggle and to achieve the dream their elders had seen for them.

Growing up in a nuclear family, I feel thankful for having parents who let me learn what I enjoyed, and in fact helped me discover my passion for journalism!