UI research may explain why measles is the most contagious human virus

Research from Professor of Pediatrics Patrick Sinn’s lab shows that infectious centers within the airways of hosts allow measles to spread throughout the environment with protection.

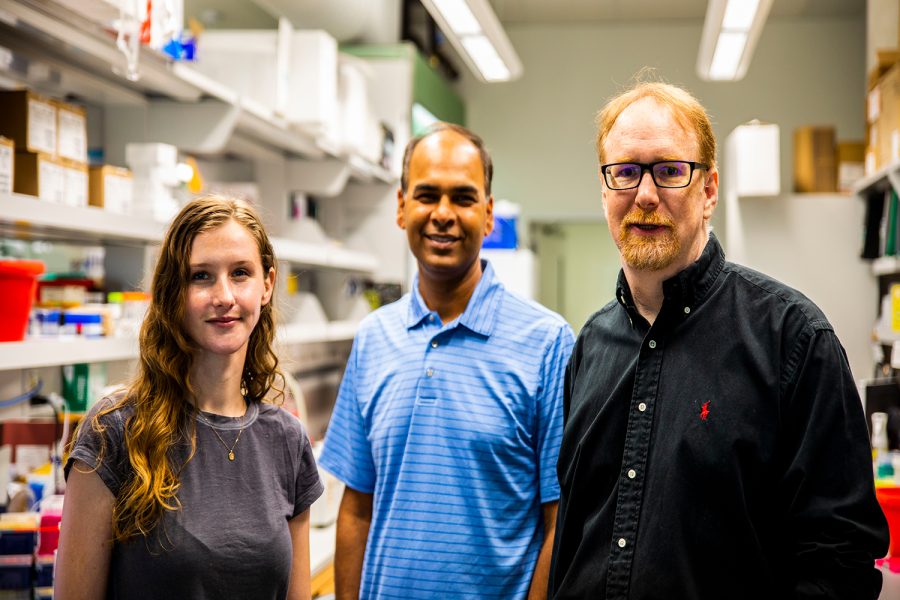

Professor Patrick Sinn right, and members of his research team Cami Hippee Graduate Student in Microbiology, Brajesh Singh Associate Research Scientist take time out for a picture on Friday, Oct. 8, 2021.

October 11, 2021

New research from the University of Iowa may indicate why measles is the most contagious human virus, as it shows how the measles virus contains itself within cells in the airways and forms infectious centers.

Protected within the centers, the measles virus is able to spread to other cells. Researchers are still trying to understand how the infectious centers fall off, said Patrick Sinn, UI professor of pediatrics and principal investigator on the research.

While the measles virus has an effective vaccine, Sinn said it is not understood why it is the most contagious human virus.

“Measles is a really interesting virus,” Sinn said. “A lot of people study measles in different cell lines. That’s another problem with measles – there aren’t really good animal models to study measles. There’s a mouse-adapted virus and there’s humanized mice, but they don’t get disease[s] like humans do. Measles only exists in humans in nature.”

Sinn said the research used a primary human cell culture sample from human donors to understand and study the virus. Sinn said answering this question is extremely important because if other viruses were nearly as contagious, the population would suffer massive casualties.

“If other viruses pick up this strategy, it could potentially be extremely deadly,” Sinn said. “If COVID was as contagious as measles, it probably would have wiped out a large chunk of the population.”

Sinn said the R-naught value, which provides a rough estimate for the infectiousness of a virus, is around six or seven for the delta variant of novel coronavirus. He said this means the virus, on average, spreads from one person to six or seven others.

For measles, the R-naught value is between 12 and 18, making it between one-and-a-half and two-and-a-half times as contagious as the delta variant, he said.

Sinn said worldwide, measles is still a deadly disease. Tens of thousands of children die from measles in Africa every year. The World Health Organization reported an estimated 207,500 measles deaths in 2019, a 50 percent increase from 2016 rates, a year with historically low numbers of measles cases and deaths.

Brajesh Singh, UI associate research scientist and a co-first author on the lab’s study, said this research is important because while measles is no longer prevalent in the United States, it is something many still deal with around the world.

“I think it’s one of the diseases people forgot about because of the good vaccine,” Singh said. “I think if you ask students [born in] the 90s or 2000s, they don’t know that measles exists anymore.”

Singh said most viruses typically spread through viral particles passing from person to person, but this research has discovered the measles virus travels in “infectious centers,” providing a more protected environment for the virus to spread.

“When you go in the environment from one person to another person, there are so many factors that can affect the stability of the virus,” Singh said. “The infectious centers — those coming out from one person — can protect the virus in the environment for a longer time so that it can be [infectious] for a longer time to the other person.”

Cami Hippee, UI graduate student and co-author of the study, said the infectious centers described in the research are just groups of cells that are all infected with the measles virus and are all found in the same area in the respiratory tract.

“We found that those whole infectious centers will actually peel up off of the airway epithelia,” Hippee said. “You get a big chunk of cells that are full of virus within them.”

She said the most important finding in this research is related to the detachment of infectious centers and their ability to spread the virus to other hosts.

Because the viral particles are more stable in these infectious centers, she said, researchers involved in the study believe this detachment is the explanation for the measles virus’ high level of contagiousness.

“When these infectious centers detach, they’re full of virus,” Hippee said. “They can actually still spread the virus to other cells. That speaks to how they can spread infection from one host to the next host.”

Future research will look at how infectious centers detach from their hosts, Hippee said.

While she said current research is still unclear on how this detachment happens, she and her fellow researchers have been able to come up with multiple hypotheses and will look to test them in future research projects.

Moving forward, Hippee said research will also focus on studying the stability of the virus and experimenting with monkeys to find out how these infectious centers work on a larger scale in living organisms.

“It’s just important to know whether it’s something the virus is doing, or if it’s something the host is doing,” Hippee said. “That’ll be really interesting and important to know.”