Why does COVID-19 burden hospitals?

A confluence of virus-caused staff shortages, high emotional toll, and rapid spread of a deadly virus is straining even the most well-prepared hospitals.

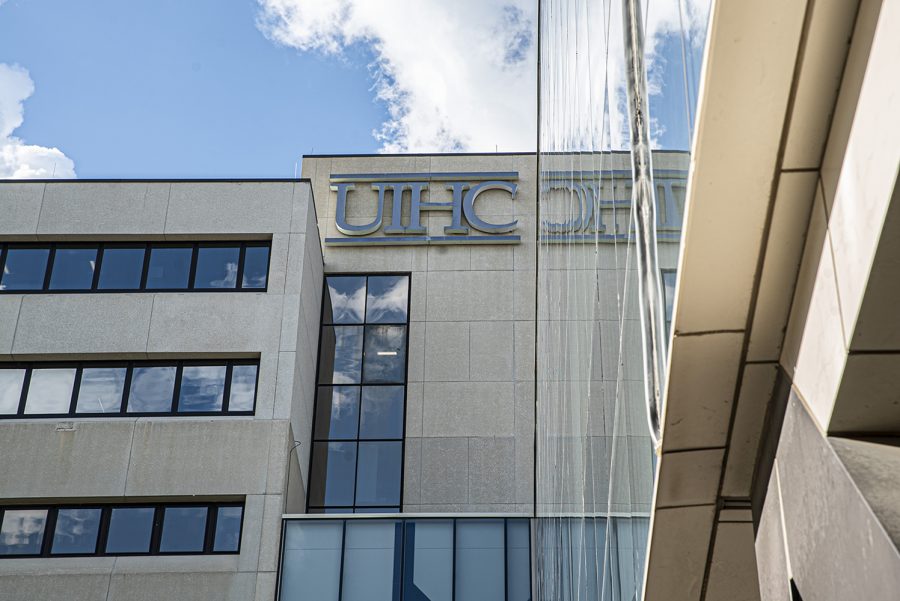

University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics are seen on Tuesday, June 23, 2020.

December 8, 2020

Theresa Brennan likes to compare a hospital’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic to being a new parent.

Cautiously laid plans are scrapped at a moment’s notice, and must be constantly reexamined and rehashed, community vitals must be monitored, and staff members undergo long hours of emotionally and physically taxing work.

“You have a newborn, and it’s exhausting, and you’re worried about them. And so, both physically and emotionally, you’re exhausted,” said Brennan, chief medical officer of University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics. “But you made a choice, right? And you love that baby, right? You love doing what you do. So, you do your best every single day. I think that’s the way our staff are.”

Hospitals like UIHC have operated in the highest gear since the pandemic began, and UIHC is a destination site for Iowa’s sickest patients. Brennan said the strain of COVID-19 on hospitals and health care workers is a confluence of multiple factors.

UIHC has opened entire units dedicated to a virus that didn’t exist a year ago — a clinic for “long haul” COVID-19 patients, an improved influenza-like illness clinic, staffed testing sites, expanded telehealth, and wings for COVID-19 patients that must be separated from the rest of the hospital.

After a surge in COVID-19 hospitalizations in November, UIHC enacted the first phase of its surge plan, which opened 10 Intensive Care Unit beds that were previously general medicine or general surgery beds.

Opening those beds required more than the space for patients to go, Brennan said, because ICU patients require a bigger space, more respiratory therapists, and physicians and nurses with proper training.

“So, identifying the spaces is the first thing, which is not easy here for us, because we’ve effectively used all of our space in the past,” Brennan said. “But the real challenge is making sure that we have the right people to take care of those patients.”

Staffers contracting the virus also removes valuable staff members. Eleven UIHC employees tested positive for the virus Monday, marking that a total of 1,276 employees at UIHC that had tested positive since the start of the pandemic.

To add flexibility, the hospital cross trained more than 1,000 people to take care of patients in a different setting. In-demand traveling nurses were also hired to fill in gaps.

It should be noted that most people who contract COVID-19 aren’t hospitalized, Brennan said, and those that do are quick to recover with IV fluids and oxygen. But intensive care COVID-19 patients have longer than average hospital stays, which requires more resources. Some need Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation — the maximum amount of support you can give a patient.

“Most patients don’t get hospitalized, the ones that do most of them are discharged in fairly quick order,” Brennan said. “But those that go to the ICU tend to stay with us a long time. And if they’re on ECMO, they can stay for weeks.”

Age matters too, in whether a rise in cases will correlate to a rise in hospitalizations. As college students flocked to Iowa City in August, hundreds of students tested positive, but UIHC didn’t see a corresponding surge in hospitalizations.

“What we saw in November was that it was a different age group that was getting COVID-19,” Brennan said. “So, we had a number of cases in the 18 to 24 range, but more in the 40- to 60-year-old range, and that translates to hospitalizations.”

If hospitalizations worsen over the holidays, a possible next step would be to delay even essential surgeries, Brennan said. When making decisions on triggering surge plans, Brennan said UIHC relies on Iowa Department of Public Health hospitalization data, monitors its own bed availability, and communicates regularly with area hospitals.

The sprawling UIHC operation has seven intensive care units — five adult and two pediatric. Usually, the hospital has 103 ICU beds and 115 pediatric ICU beds. Recently, UIHC converted 10 additional hospital beds from another unit into ICU beds as part of its surge plan.

The week beginning Nov. 27, 96.4 percent of UIHC’s ICU beds were occupied on a seven-day average, according to data released by the Health and Human Services Department.

The pandemic has been especially emotionally draining because of its death toll.

The state reported on Tuesday to date 2,919 total deaths because of COVID-19 in Iowa, the disease caused by the coronavirus. To put those numbers in context, an estimated 107 Iowans died from H1N1 in 2009, and 659 Iowans were hospitalized. In 2019, 336 Iowans died on the road in traffic accidents.

“I think most of us hoped that we would not be sitting here in December, and still have an ongoing pandemic with a recent surge in cases,” Brennan said. “So, the timeframe has really been long.”

At the start of the pandemic, people with allergies or other symptoms of the virus crowded into wait rooms and UI Quick Care sites to check if they had the virus. A need to depopulate the hospital campus prompted Katie Imborek, a clinical associate professor and director of off-site care, to spearhead UIHC’s expanded telehealth units.

Now, UIHC health care providers are routinely doing over 1,000 telemedicine visits a day, which requires about 33 providers an hour for 12 hours, Imborek said. She said it doesn’t shorten staff time, though it does relieve the number of nurses needed since in-person vitals aren’t taken.

When UIHC was inundated with calls from students with flu-like symptoms making telehealth appointments in August, Imborek called a student who’d reported having a cough. Imborek was running a good half hour behind in appointments, and the student was on the road to his aunt and uncle’s house in Des Moines when she called.

“I tell him, ‘I really think that you might have COVID,’ and he said, ‘Yeah but my symptoms aren’t that bad,’” she said.

He turned around to head back to Iowa City, and tested positive for the virus the next day.

The student thanked Imborek once she called him about his test result.

“I think that that’s such a great story about how we’re banking on having that very personal interaction with a provider that can actually change some behaviors of our patients,” Imborek said.

![Advanced Registered Nurse Practitioner (ARNP) Liz Highland twists the lid on a sippy cup at her home on Monday, Nov. 23, 2020. Highland works two twelve-hour shifts at the ILI Clinic per week and helps with telemedicine and administrative tasks throughout the week, adding up to 45 hours in a regular work week. On nights when she arrives home after her husband Corey and 18-month-old daughter Loah have gone to bed, Highland usually takes a shower, eats dinner, and does dishes, laundry, or other household tasks in a quiet house before bed. “It’s kind of sad to me, but [Corey] is a student also, so a lot of times even when I do come home we don’t have a lot of time to sit and chit-chat ‘cause he’s doing homework or like today he got up at 4:30, he’s got to get up at 4:30 again.” Highland said, adding that it works for childcare but she and her husband never see each other.](https://dailyiowan.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Top-3-475x317.jpg)

![Advanced Registered Nurse Practitioner (ARNP) Liz Highland twists the lid on a sippy cup at her home on Monday, Nov. 23, 2020. Highland works two twelve-hour shifts at the ILI Clinic per week and helps with telemedicine and administrative tasks throughout the week, adding up to 45 hours in a regular work week. On nights when she arrives home after her husband Corey and 18-month-old daughter Loah have gone to bed, Highland usually takes a shower, eats dinner, and does dishes, laundry, or other household tasks in a quiet house before bed. “It’s kind of sad to me, but [Corey] is a student also, so a lot of times even when I do come home we don’t have a lot of time to sit and chit-chat ‘cause he’s doing homework or like today he got up at 4:30, he’s got to get up at 4:30 again.” Highland said, adding that it works for childcare but she and her husband never see each other.](https://dailyiowan.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Top-3-300x200.jpg)