From high school dropout to UI administrator, Maria Bruno is an ‘inspiration’ to Hawkeyes

Maria Bruno assumed the role of Director of Belonging and Inclusion in October of 2019. But for Bruno, a high school dropout and daughter of immigrants, the path to get to that position involved many turns.

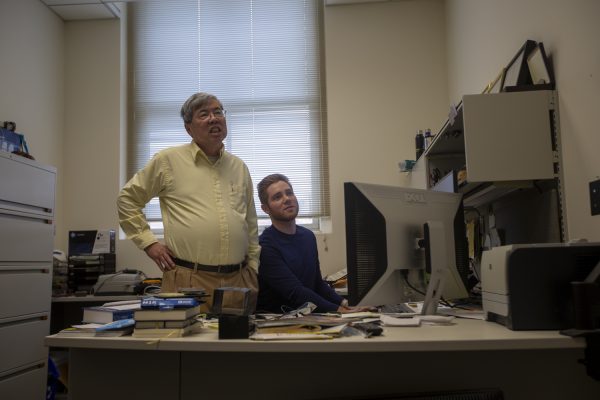

Executive Director for Belonging and Inclusion Maria Bruno poses for a portrait in the Iowa Memorial Union on Monday, March 2, 2020.

March 9, 2020

In college, Maria Guadalupe Bruno’s nickname from her sorority was “inspiración,” or inspiration.

As an adult, that nickname has found new meaning. Formerly a high school dropout, Bruno has earned three degrees and is now the Executive director for Belonging and Inclusion within the Division of Student Life. And the story of how she got there, reflects her nickname, fellow Hawkeyes say.

Since Bruno assumed the position in October, she’s best known for spearheading the move of Student Disability Services from the basement of Burge and chairing a number of committees and teams, including the Implementation Team for the Division of Student Life Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Action plan, the Accessibility Action Team, and the Equity Committee.

“As a student on campus who is marginalized, she’s someone that definitely listens to me and my voice,” said Christopher Vazquez, a UI student and a founding member of the #DoesUIowaLoveMe movement, which started on campus in 2019 after concerns from students about support for Hawkeyes from underrepresented communities. “[She’s] someone who cares and she’ll care for you even if she doesn’t know you yet.”

For Bruno, supporting students is the most important part of her job, and it starts from her office doors. Scattered around her workplace in colorful clusters are posters and pins, highlighting empowerment and diversity.

I <3 Civil Rights, one says. Value all voices, says another. I’m proud to support first gen @ Iowa.

Every poster and pin highlights a group that has often felt voiceless and pledges support. One rainbow poster adorning one of her cabinet doors reads LGTBQ Safe Zone.

“I want people to feel the way I have felt,” Bruno said. “Where people have really supported me and encouraged me. That’s what helps us thrive.”

Bruno’s Beginnings

Bruno is the daughter of two immigrants. Born in Mexico, the now 45-year-old old moved to the northwest Chicago suburbs when she was 5. Her parents both worked in hotels: her mother as a housekeeper and her father as a janitor.

She spent her childhood growing up in what she described as a very challenging neighborhood and was forced to attend group therapy for children who lived in at-risk homes by a social worker.

“This person thought she would save me from my environment,” Bruno said.

The social worker removed her from her home at 15 years old. Bruno spent the next three years living in shelters and group homes. Because of the constant shifting, Bruno dropped out of high school before age 16.

“When people ask me where I grew up, it’s really hard for me to answer that question because I was removed from my home,” Bruno said.

She had no education and her removal was difficult for her family, ultimately leading to her parents’ divorce.

“I didn’t have anywhere to go,” Bruno said.

It was the military that changed her life. After meeting an Air Force recruiter, he took her for a pre-test for her GED and, after she performed well, she took the test and passed.

Three days later, Bruno packed her bags and left for Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio.

Bruno wanted to be a medical doctor and began her time in the Air Force as a medical assistant. During that time, they tested possible candidates for an EMT program and Bruno was shocked to learn she was one of five people who had performed extremely well.

“I didn’t think I was one of those folks because I didn’t have the high-school education and background a lot of my peers did,” Bruno said.

Following the EMT testing, Bruno traveled to the Walter Reed Army Medical Center, where she specialized in allergy immunology and anaphylaxis treatment.

“I felt like people invested in me,” Bruno said. “I felt like people really wanted me to succeed. And so because of that experience, I made a commitment to myself to make sure I do the same for other folks.”

That commitment eventually led her away from becoming a medical doctor. The physicians in the internal medicine clinic encouraged her to pursue psychology.

“Now in the Latino community, that (psychology) is not a thing. In the Latino community, they’re like, ‘Oh, we don’t believe in that, that’s for crazy people,’ ” said Bruno. “And so I had to kind of make meaning of that for myself and say, “Well, you know, if I do that, what is my family going to think? What is my community going to think? But at the end, I decided you know what, I need to do this, for my community, for my family, for people.”

Her internal struggle brought her to a Psychology 101 class at a local community college, where she fell in love with the practice and decided to pursue it.

Following four years of active duty with the Air Force, Bruno finished three years in the National Guard before leaving the military to pursue a college degree . She graduated with a bachelor’s degree in general studies and a major in psychology from Roosevelt University in 2003 before pursuing her master’s in clinical psychology at the Chicago School of Professional Psychology in 2005.

Bruno’s photo of her graduation is placed in a brightly printed frame stuck to the wall above her desk with her name, Maria, written in pink below and surrounded by colorful pins like a rainbow button with the message celebrate diversity, and a circular pin with BLACK LIVES MATTER inscribed.

Picture

After she completed her master’s, Bruno began to work in a juvenile detention center as a forensic psychologist, where she would conduct psychological testing and qualify as an expert witness in court. She testified why a person behaved the way they did and made recommendations.

Bruno saw it as a way to advocate for those who could not advocate for her themselves and, instead of describing her reports in clinical terms, Bruno liked to call it “telling the person’s story.”

At the same time, Bruno began her doctoral program in the Illinois School for Professional Psychology for her Psy.D in clinical psychology. The decision to obtain her doctorate came after the director of the juvenile detention center encouraged her to pursue it.

“If I’m being completely honest,” said Bruno. “That’s what I thought the rest of my professional life was going to be, being a forensic psychologist, but sometimes life has a funny way of placing us in different roles.”

She spent six years at the juvenile detention center before shifting careers again. She worked simultaneously as a consultant for inclusivity at the Fortune 500 company 3M, and as the director of a community mental health center in Dekalb, Illinois.

Her path finally crossed with Iowa City in 2014, following her partner’s career change from a psychologist at the juvenile detention center to the director of retention at the UI’s athletic department.

“I came here in support of him,” Bruno said.

For her first six months, Bruno spent her time working on her dissertation and finally finished her doctorate for clinical psychology in 2015, eight years after she started.

Afterward, she joined the University Counseling Services as a staff psychologist, where she stayed until 2019 when her inbox began to fill with messages urging her to apply for a new role as the Executive Director for Belonging and Inclusion at the UI.

The role, created by former Vice President for Student Life Melissa Shivers, was a new position that grew out of the #doesuiowaloveme movement.

Bruno’s students and campus partners kept forwarding her the link to the job position, writing to her to say she would be the perfect person for the job, but, as Bruno said, she laughed and told them she wasn’t looking for a new position.

“After I got the tenth one, I finally opened the link,” Bruno said.

That click led her to a job that she felt could challenge her professionally and, after talking with her family and consulting her mentors, Bruno eventually applied for the position and was hired. She began her role Oct. 7, 2019.

Bret Gothe, the assistant to the Vice President of Student Life who worked with Bruno on the SDS project, touched on what she’s done so far.

“In the short time she’s been here, she’s made significant contributions to really moving forward conversations around diversity, equity, and inclusion and so much of that has been focused on student success,” Gothe said.

Students, Bruno said, are the entire reason she’s here. Within her office, she’s initiated an “open door” policy. Within her office, students in need can sit in comfort, surrounded by posters that remind them that they are heard and valued.

She believes that supporting students should work on all levels, all the way up to administration, she said. Being accessible to students, she added, is important to her.

“Students are amazing,” she said. “I am here because it is an honor to be a part of students’ early developmental processes and be able to hear the different stories and experiences. And to be able to be a part of those people’s journey, I think, is amazing.”

As a leader, Bria Marcelo, the Director of Diversity Resources, described Bruno as exactly what the division needed. Marcelo has known Bruno personally since she became a staff counselor on campus and has worked with her on multiple occasions.

“I think about leaders who can impact you on a personal level because you get to know them,” Marcelo said. “Because you get to connect to them socially (and) connect to them their story. And I think there’s also leaders you follow because you think they are charismatic. They are clearly strategic and organized, they’re forward thinkers, they’re just brilliant. And I think Maria has both of those things.”

Identity on the job

To Bruno, the hardest part of her job is bridging the gap between the administration and students who are hurting, who may feel marginalized, oppressed, or not included. For marginalized students, Bruno says, you hear their hurt and their pain over and over and the system, organizations, policies, and procedures don’t move as quickly as those students would like.

“We see you, we hear you, and we recognize that you are hurting,” said Bruno. “And here is what we’re trying to do… Everything is a process.”

As a woman from an underrepresented group herself, Bruno described some of the challenges she can face as a leader in higher education. Occasionally, she said, it can be difficult to be one of the few people in the room to bring up specific concerns as they are related to marginalized groups.

“At some times, it does get frustrating to be one of the few voices that says, ‘Hey, have we thought about this?’ Or ‘Have we looked around the room and noticed who’s not here? Which voices aren’t present? How are we making sure we are including those voices?” said Bruno.

As for her own identity, Bruno described the changes she has faced since coming to Iowa.

“The way I identify myself and the way I describe myself typically isn’t as a woman of color and underrepresented background,” she said. “I know it is a part of my identity but it’s not my most salient identity. And since coming to the University of Iowa, that seems to be the first identity everyone sees. So that’s been a shift for me.”

In some conversations, Bruno said, her identity can be helpful, neutral, or work as a barrier, but it largely depends on what she is doing or who she is with. She tries to scan the room and identify and connect with others who may be open to hearing different opinions.

“I try to listen and try to understand,” Bruno said.

Moving forward, she said she wants to continue to strive to build a diverse, inclusive campus for all voices by asking critical questions, educating herself, conducting conversations with campus partners, and meeting with three to four students a week to see how they are doing.

“I think that if we all have folks that care about us, that show up for us and guide us when we make mistakes then I really do think that we, as people, can be brilliant individuals and we are able to thrive,” Bruno said.