Pressures abroad: Hong Kong and University of Iowa communities intersect

One UI student talks about their experience protesting in Hong Kong, unveiling a deeply rooted ideological divide among cultures and generations.

One University of Iowa student would’ve been among the 400 arrested at Causeway Bay in Hong Kong on Jan. 1 had they chosen to stay at a pro-democracy protest just 15 minutes longer.

“I feel relieved, but I don’t feel happy,” the student said after returning to Iowa City.

The Daily Iowan chose to grant the student’s request to remain anonymous and not to reveal the student’s year or program of study, because of safety concerns.

There are only 16 undergraduate students from Hong Kong at the UI, but from 7,600 miles across the world, unrest in the country has taken hold of the international student community on campus.

The student traveled home in December during winter break explicitly to participate in pro-democracy protests. While fellow peers were stressed about final exams, this student had the added weight of knowing their future at the UI was at risk with the possibility of being arrested in Hong Kong.

“Basically, I just believe that I’m doing the right thing,” the student said before departing for a two-week trip home.

Hong Kong has experienced a series of both peaceful and violent protests that started when the Hong Kong government supported a national bill that would have allowed extradition of Hong Kong citizens to mainland China. In response to concerns over Hong Kong’s judicial independence, the bill was suspended in September, but pro-democracy protests have turned into a greater movement against Beijing’s reach into Hong Kong’s governmental system.

In 1997, the British ended their 157-year rule of Hong Kong, forming an agreement with the People’s Republic of China that Hong Kong would remain mostly autonomous for 50 years — this agreement became known as “one country, two systems.” 2047 will be the year that Hong Kong is reunited with China — but Hong Kong citizens want democracy now.

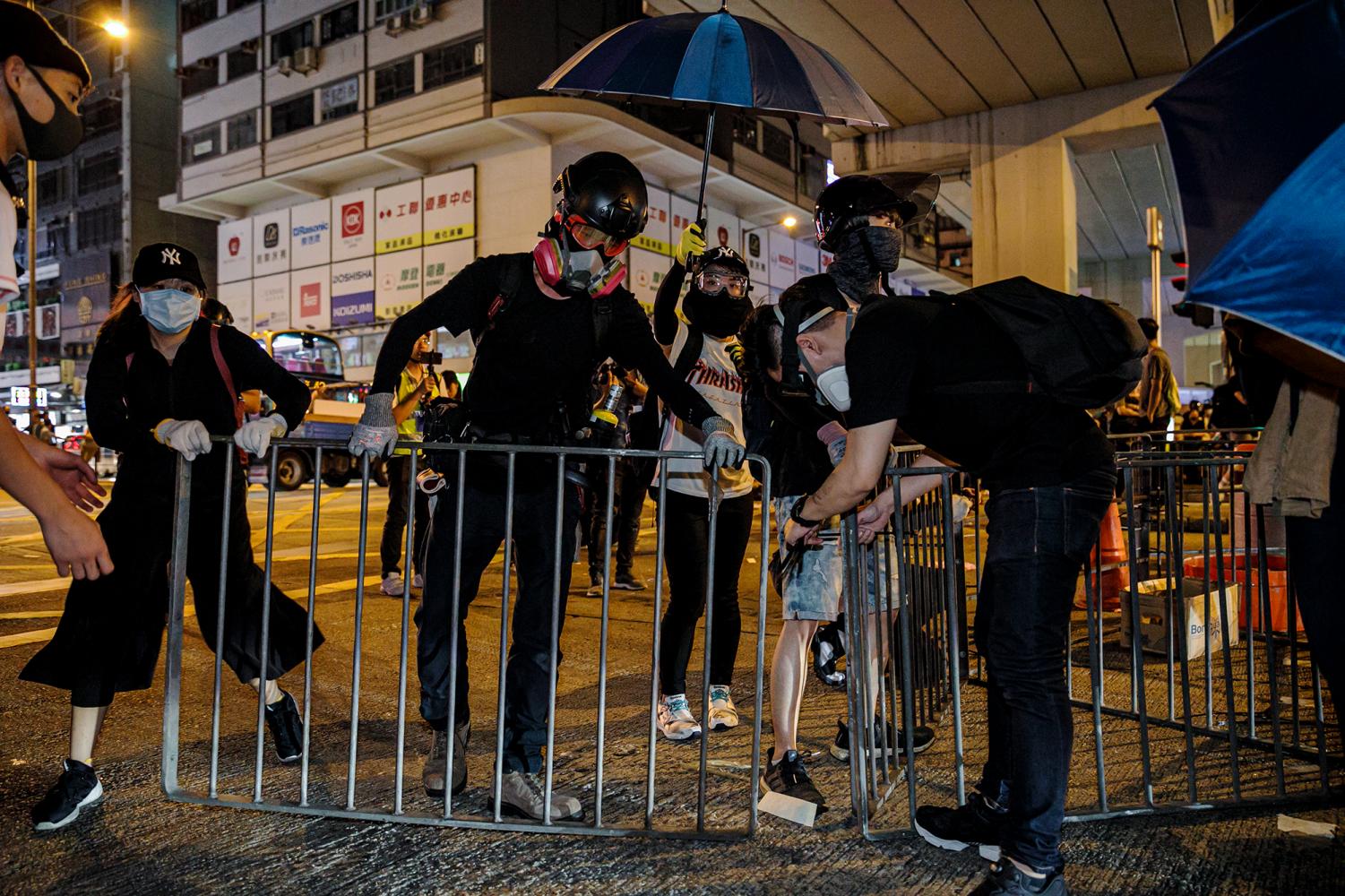

On June 12, 2019, Hong Kong police used tear gas for the first time. Since then, tensions between protesters and the Hong Kong government have only increased, with more than 7,000 protesters arrested, police beginning to use live rounds, and over 2 million people taking to the streets to rally for their full independence from the Chinese Communist Party.

Human Rights Watch reported in December that Hong Kong police have used 10,000 rounds of tear gas against protesters.

“The protests are peaceful before the police arrive,” the student said, saying most protests always start out peaceful until police intervene with unnecessary brute force.

Along streets that were once familiar, the student said dozens of police were posted around high-traffic areas, such as supermarkets and banks, holding military-grade guns, even when there wasn’t a protest planned.

The student described Lennon boards — bulletin boards and walls in various locations across Hong Kong where people post information about upcoming protests, which have also often been sites of violent clashes between police and citizens.

At the New Year’s Day rally in Causeway Bay, the student said more than 1 million protesters had a permit from the city that allowed them to legally assemble on that property. Police broke up the rally long before the agreed-upon time was up and gave everyone half an hour to leave the premises, as reported by the South China Morning Post. The student said that anyone who was left in the area after 30 minutes was arrested.

“My parents called me basically every hour to make sure I was safe,” they said.

The student said that while the protest was loud and well-attended, they did not see any protesters with weapons. Packed onto the streets were people dressed in colors and symbols synonymous with the pro-democracy movement — yellow ribbons, X-shaped crosses, and face masks.

The student said there are group chats where people plan and discuss protests, and protesters use apps to warn people where police are and which local stores and restaurants do and don’t support the pro-democracy movement.

Hong Kong’s District Council elections were held on Nov. 24, and pro-democracy candidates took 392 of the 452 seats. Now, the student said, citizens are protesting under five key demands: A complete withdrawal of the extradition bill, criminal charges to be dropped against protesters who were arrested, for the state to claim the uprising as a legitimate protest rather than a riot, investigations into allegations of police brutality, and universal suffrage.

The student said the coronavirus outbreak has changed the level at which people are protesting because people in Hong Kong are now more cautious about gathering in large groups. The student said it’s ironic, because before the outbreak, the police arrested people just for wearing masks as a symbol for the protests, and now there aren’t enough masks to go around.

Another person, a recent UI graduate from Hong Kong whose request to remain anonymous the DI granted because of safety concerns, said her mom traveled from Hong Kong to mainland China when her grandfather was admitted into a hospital, and then returned to Hong Kong to participate in a pro-democracy march.

The UI alum said she feels removed from the conflict being in the U.S., and wishes she could do more to help the protesters. She said she vividly remembers the night of July 21, when she read about a riot that broke out in a Hong Kong subway station and a mob of men dressed in white T-shirts armed with batons started beating groups of protesters. Most upsetting to her, she said, was that Hong Kong police did not immediately respond to emergency calls involving protesters from that night.

“Every weekend, and when I have my days off, and I was all by myself … and not surrounded by other people, I would have mental breakdowns every single day,” she said.

She said she has communicated some with friends who are protesting in Hong Kong. She said she’s heard stories of young people getting arrested, not being heard from for days, and then being found dead in places around the city that police frame as suicides. She said her friends have made pledges on social media that if they disappear, it is not because they committed suicide. When people get arrested, other protesters will quickly try and get their information and shout their name so people know they are in police custody, she said.

She said she will go back to Hong Kong in June because that’s when her visa expires, and said it will be a long process before she can apply for another visa to eventually stay in the U.S.

In late November, President Trump signed a law supporting pro-democracy protesters in Hong Kong, which would require the U.S. government to do yearly check-ins to confirm Hong Kong’s special freedoms are being upheld by Beijing. The UI alum said she was happy to see that U.S. support after the last six months of unrest.

“This protest definitely [made me consider] leaving Hong Kong, which is sad and a hard decision to make, but I think it’s an obvious choice,” she said. “And I’m blessed enough to leave the country, because I know a lot of my friends couldn’t because they don’t have enough money to do that.”

Interactive timeline: Key Hong Kong pro-democracy events from March until now

Timeline created by Aadit Tambe

A cultural and generational divide

A UI graduate student from Hong Kong said if he was 10 years younger and in his undergraduate program, he would most likely participate in the pro-democracy protests. He’s in his 30s, and said younger generations in Hong Kong are much more political than what he remembers growing up.

The DI also honored the graduate student’s request to remain anonymous because of the sensitive subject matter.

He said that what matters to him most now is being able to find a job to afford the high housing prices in Hong Kong. He said his parents, like other people in Hong Kong, are frustrated with the protests disrupting the normal flow of everyday life.

“I just want to go home to visit my relatives, my friends, my family — it has been one year and a half,” he said. “It’s hard.”

He said that worsening circumstances in Hong Kong, with protests continuing and now a coronavirus outbreak, have prevented him from being able to travel home.

He added that even though pro-democracy officials now hold a majority in the Hong Kong Legislature, district councilors do not make laws, and instead oversee constituent work.

Matthew Noellert, UI assistant professor of history and modern China, said the news media in the U.S. tend to homogenize the political viewpoints of people in Hong Kong, reporting mostly about how people have negative feelings toward Beijing. Noellert said political views of the Chinese government are divided in Hong Kong among generations.

He said a lot of that has to do with the urban/rural divide, with a lot of older people living in the countryside. He said generations of people there before the British came viewed the British as outsiders, and that some in older generations still hold that viewpoint.

“And so that creates a lot of confusion, because for Hong Kong — these young people, they talk about restoring Hong Kong,” Noellert said. “But for [older generations], restoring Hong Kong is restoring it to colonial rule basically, which for a lot of people seems crazy.”

Noellert said he has noticed tension on campus between students from Hong Kong and students from mainland China who support the Chinese government and disagree with the pro-democracy protests. He said that when this subject comes up in courses, it’s such a polarizing and politicized issue that “no real dialogue” happens between students who may disagree.

The graduate student referenced earlier said he’s noticed that different Asian communities on campus tend to segregate themselves — Korean students hang out with other Korean students, Chinese students hang out with other Chinese students, etc.

“A lot of mainland students have pretty strong feelings for the opposite of the Hong Kong view,” Noellert said. “I’ve noticed that the mood, and the politicization — the polarization, is definitely on this campus as well.”

He said people protesting the CCP are viewed as separatists by people from the mainland. He said separating from the mainland is unacceptable in terms of Chinese nationalism and Chinese sentiments about the country’s place in the world, which has a lot to do with the country’s history. He said China’s education emphasizes this period of victimization when the country was under foreign imperialism by the British, and now they have this “newfound strength.”

“I’ve actually had some students, former students as well, come talk to me about it because they’re kind of very conflicted about it, because they can see both sides, being here,” Noellert said. “So they also are very unsure of what to feel or believe.”

The student who recently went home to protest said they’re focused on working and studying in preparation for their December graduation. Despite having friends and family in Hong Kong, they do not currently have plans to return home.

“For now it seems like … if you’re just in the protest, it doesn’t matter if you are being violent or just appear there with your mask, wearing black, and you’re young enough, the police will arrest you no matter what you did.”

(she/her/hers)

Email: [email protected]

Julia Shanahan is the Politics Editor at The Daily Iowan and a senior at the University of Iowa studying...