Opinion | Generalizing “African” can do harm to diverse populations in Africa

To avoid appropriation of African cultures, the U.S. rhetoric stating Africa is home to one culture and an exclusively Black population needs to be criticized and rewritten.

April 5, 2022

U.S. rhetoric and structural systems about Africa often equate Blackness and African culture in an exclusive and synonymous way.

April is National Arab American History Month. A large portion of Arab people reside in North African regions alongside indigenous North African tribes, mostly notably the Amazigh.

This false equivalency has encouraged colonization and appropriation of African nations by Black folks living in the U.S. who don’t have an ancestral or cultural claim to the continent as it exists today.

The U.S. Census currently defines “African Americans” as referring only to “a person having origins in any of the Black racial groups of Africa.”

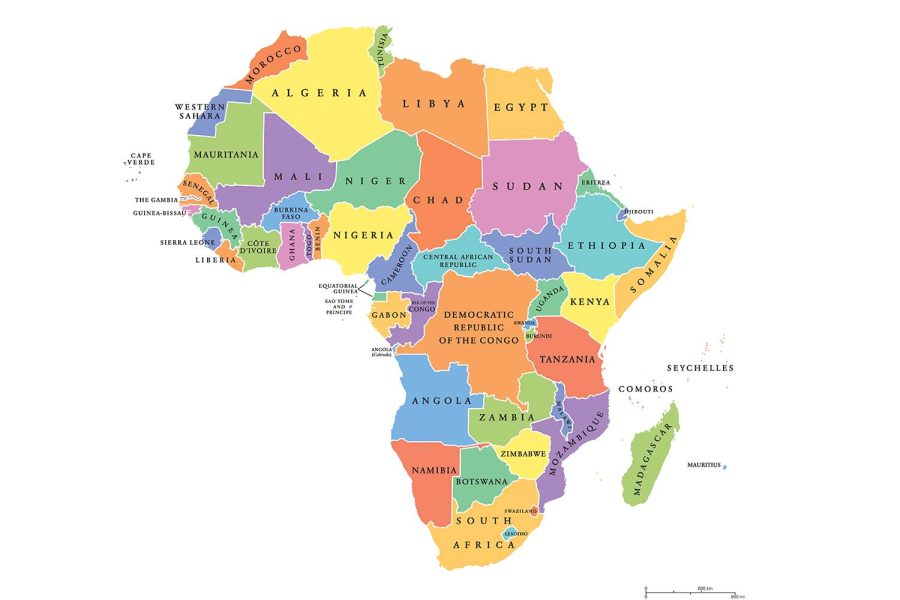

In the U.S., “African” is used in both a universal sense, as though all of Africa is one culture, one nation, lacking diversity. It is also used to describe only countries and peoples living in Sub-Saharan regions, excluding at least five countries — over 250 million people — who exist on the continent’s land mass.

Why is one of these regions considered African and the other not? Skin tone.

Contrast to common American belief, the 54 African nations recognized today are split in their Christian and Islamic dominant belief systems, speak a variety of native and global languages totaling over 2,000, and are home to white, Brown, and Black people.

The following must be said: it is not the fault of one’s ancestors if slavery or colonization efforts forced them away from their cultures, languages, beliefs, and other ways of life.

This is the unfortunate reality for many Black people living in the U.S., — ancestral culture is not inherently that of descendants to claim.

Culture is not stagnant, rather constantly evolving. The consequence of this can be that a culture or practice may have changed since a person’s ancestors were forcibly removed.

This was felt in the 1920s with the rise of Black nationalist action under Garveyism.

Although Marcus Garvey — the namesake for Garveyism — was a descendant of Jamaicans, he convinced many Black people living in the U.S at the time to develop a “Black Star Line” and establish a Black state on the western coast of Africa.

When the first voyage of the Black Star Line landed on the Liberian coast, many chose to return to the U.S. as descendants of and previously enslaved Black folks did not speak the languages, understand the customs, or have a connection to the 1900s Africa they landed on.

While important to recognize that many Black leaders in the U.S., including W.E.B. DuBois, did not agree with Garvey’s idea of a Black state in Africa, practices that reinforce the idea that Black people are the only ones with a claim to African or Afro culture continue today.

Haiti, the Caribbean, and Jamaica are all non-African places where Black immigrants in the 20th and 21st century originated from.

The 2020 Census included a spot for “Black or African Americans” to write down their place of origin.

In a conversation with NPR in 2018, Fordham University Professor Christina Greer shared that she planned to write “Black American” for her origin since writing only “Black” was not an option.

Greer shared that her identity as “J.B.” or “Just Black” stems from acknowledging forced removal of her ancestors from their culture through slave trade in the 17th-19th centuries.

Greer’s explanation and decision, although disheartening, represents the only way that those without a direct cultural tie to Africa can avoid appropriation.

The distinctions between Black people born and raised in the U.S compared to immigrants from African countries goes beyond nation of origin.

Similarly, studies based outside the U.S note an issue with the country’s demographic categorization that is often ignored by American researchers.

For example, recent studies in the U.K note that 20th and 21st century immigrants from African regions and Black peoples who have been in the U.S for centuries have vastly different ways of life, genetic health risks, and native languages.

Another common distinction between recent African immigrants and those possibly from an African culture who are unsure of their heritage is the terminology used to describe their background.

While not a studied topic due to the label of African American as standard practice for U.S demographic forms, many people in the U.S. will consider “African” an identity. This is widely unspecific compared to how more recent immigrants from an African region discuss their heritage.

Colonizing nations did not base their actions on an idea that two sides of Africa exist. Enslaved, raped, pillaged, and essentially destroyed nations exist in all regions of the continent. My home country of Morocco was colonized by the French and Spanish until 1956, and our other North African neighbors saw similar harm from Italian and English troops.

Nomadic behaviors did not pay attention to Western enforced political borders either. Although my immediate family members were born and raised in Morocco, my genetic reports read Sierra Leonean, Ghanian, Egyptian, and Amazigh or a tribe originally referred to as “Berber.”

Indigenous North Africans — traditionally lighter-skinned peoples — were given the colonized name of Berber by the Spanish to connect them to barbarians. Just like Sub-Saharan countries, North African indigenous peoples braid their hair, perform tribal ceremonies and dances, as well as speak unique languages from other peoples living in the regions they originally called home.

I don’t have any answers and, in research for this article, those with more expertise than I also seemed to be at a loss.

The question I am left with is: is it right to justify actions of appropriation and colonization as a response to one’s own oppression?

If the answer is no, then steps must be taken to end appropriation of African cultures for those who do not have cultural awareness, language, or religious ties to the continent as it stands today.

Columns reflect the opinions of the authors and are not necessarily those of the Editorial Board, The Daily Iowan, or other organizations in which the author may be involved.