Where does Iowa stand in flattening the coronavirus curve?

As Iowa continues to grapple with an increase in coronavirus cases, ‘flattening the curve’ has become a battle cry of the global pandemic. When thinking about how many people deal with a ‘new normal,’ however, UI Anthropology Professor Andrew Kitchen said it is important to look at history.

Graphic by Katina Zentz

April 23, 2020

Iowa is still a dozen days out from the state’s projected peak of COVID-19 deaths, according to the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington — Iowa’s peak follows that of the nation’s, which was estimated to have been a week ago.

University of Iowa anthropology Professor Andrew Kitchen said Iowa is behind the nation’s expected curve because infectious diseases tend to spread more quickly in urban settings. The state of New York had its expected peak two weeks ago, according to the University of Washington metrics.

“[My wife and I] haven’t gone to the store for the past two weeks and really haven’t interacted with anybody,” he said. “Now, if you live in New York in an apartment complex, even if you take the stairs you’re touching a banister that has been touched by 400 other people … it’s a more intensely urban issue, but eventually it will reach more rural settings.”

Iowa had 3,924 cases of the virus as of 11 a.m. Thursday. Tuesday saw the largest single-day increase in cases with 482 testing positive. The same day, Iowa Gov. Kim Reynolds announced the launch of Test Iowa, a website that allows Iowans to input their personal information and symptoms and find out if they are eligible for testing in a $26 million partnership with a Utah-based company.

The month of April is usually a jubilant time on the University of Iowa campus — graduating seniors congregate on the Pentacrest clad in black and gold gowns while droves of students cram for final exams. This year, however, the novel coronavirus pandemic has turned the once-bustling campus into what may be commonly referred to as a “ghost town.”

Although it may seem as though the streets of Iowa have been desolate for ages, COVID-19-mitigation efforts such as social distancing and nonessential business closures have one simple yet difficult goal in mind — reducing, and ultimately eradicating, new cases of the virus in the Hawkeye State.

Few people know the importance of infectious disease mitigation efforts better, perhaps, than UI microbiology and immunology Professor Stanley Perlman, whose lab has studied coronaviruses for years. According to the World Health Organization, coronaviruses make up a large family of viruses that can infect birds and mammals and can be transmitted to humans.

When addressing an unprecedented situation, Perlman said it can be difficult to make the right call when thinking about how to best protect different populations.

“Some people would say that [Iowa] should have been sheltering in place, but I think it’s a hard call to know exactly what the best course of action to take is. I think it will be more obvious when this is all over,” he said. “Certainly if you save lives by sheltering in place it will have been worth doing, but there will be people with economic problems because they cannot make money for the weeks they were stuck at home.”

Despite the possibility of these economic hardships — the main concern that a $2.2 trillion stimulus package passed by Congress aims to address — Perlman said mitigation efforts have already had an impact on Iowa’s ability to diminish new cases in the state.

These efforts, however, are not limited to interpersonal restrictions such as the cancellation of this year’s RAGBRAI and Iowa City Pride celebration. When thinking about the essential businesses that remain open, Perlman added, it is important to keep in mind the safety of those workers.

Reynolds, who announced on Monday increased surveillance testing for essential businesses amid an outbreak of the virus in at least two Iowa meatpacking plants, shared this sentiment.

“We’re not that far from it, and it will be devastating,” Reynolds said during a Monday press conference, of the long-term impact of the virus. “Not only for the food supply but for the cost of food going forward.”

At Reynolds’ daily coronavirus briefing Wednesday, she said 80,000 Iowans have already used the Test Iowa site to log their symptoms.

Although it is currently unclear when the coronavirus curve will flatten, Perlman said Iowans’ ability to hunker down will have the most salient impact in the long run.

“It may not seem like we’re doing much now, but looking back on this in the future, we don’t want to be in the position of asking ourselves what we could have done different,” he said.

When asked how long Iowans will be stuck at home for, Kitchen said it depends on “our willingness” to adhere to mitigation efforts, but cautioned that the coronavirus is not like flipping a switch — in short, it will be months before “our lives seem normal again.”

“I think this is going to last a lot longer than people think it will,” he said. “Large groups of people — like at a football game — will only be safe once we have a vaccine.”

Flattening the curve — through a historical perspective

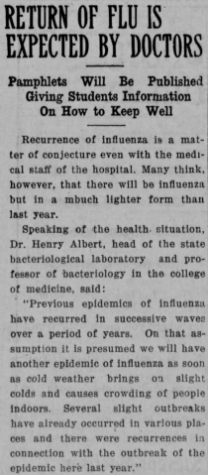

Comparisons are often made between the 2019 novel coronavirus and the 1918 Spanish flu epidemic — to Perlman, these comparisons are not without foundation.

“The world was so different in 1918 in terms of what our preparedness was, and we barely knew what viruses were, let alone their impact,” he said. “We didn’t know about transmissibility or airborne spread versus contact spread. Where these two times are similar, though, is in some leaders’ views that this is not ‘our problem.’ When someone says that this isn’t our problem and we’re well-prepared for [a pandemic], neither part of that statement is true.”

Perlman said large groups of people continued to congregate as the Spanish flu spread across the United States in 1918, largely unaware of transmissibility in large social gatherings. Although long-distance travel was not a pressing concern during this time, a surge in larger cities meant more deaths and a longer — and more dangerous — curve.

Today, in a time that Perlman politely described as “polarized,” it can be difficult to contain outbreaks in larger cities when people are not “working as a team.” This was recently exemplified in Michigan, where thousands of protestors took to the streets to oppose Gov. Gretchen Whitmer’s stay-at-home orders.

Kitchen said as long as there have been widespread infections, subsets of the population have attempted to put the blame on external factors unrelated to the “natural phenomena” of disease.

“The Black Death jumped from a rodent reservoir to humans and devastated Europe,” he said. “And what happens is most people have a difficult time accepting the fact that this is just a natural thing that happens. If you look around, [some would say] it’s just inconceivable from the way we live our lives.”

In the U.S. and other developed countries, Kitchen said it can be hard to reconcile with the inevitability of a pandemic when the threat of malaria and other diseases is virtually nonexistent.

“Explanations for disease often come from preexisting beliefs,” he said. “During the Black Death, a lot of it was, ‘Oh, God is angry at us.” You have people doubling down on Christianity and religion … there’s always this idea that there’s got to be this grand design, it can’t just be this natural phenomenon that happens.”

This scapegoating, Kitchen said, is not always turned toward God — in the internet age, he added that once-fringe ideas suddenly have a worldwide platform.

“We’re seeing that today with all these conspiracy theories,” Kitchen said. “It can’t just be that this emerged in China and spread through the Chinese population faster than authorities understood – it has to be something else, like 5G, because most of our 5G technology comes from China. That’s how we get a phrase like ‘the Chinese Virus.’ ”

Kitchen also said that racial scapegoating, which has been targeted toward Asian Americans during the coronavirus pandemic, is not a new occurrence. During the Black Death, Jewish communities were targeted as the “source” of the disease.

In both cases — the Black Death and the current coronavirus pandemic — Kitchen said after an initial period of shock, a large percentage of the population adjusted to the new, temporary normal. With that said, however, he added that some will continuously go against the grain.

“There will always be some sort of grasp for these pre-existing prejudices about these groups,” he said. “It seems to be something that recurs over and over, but of course over time people change their views.”