‘The Space Between’ exhibit by Edward Kelley facilitates communication across static

From Nov. 18 to Dec. 3, Edward Kelley’s ‘The Space Between’ exhibit at Public Space One’s North Gallery facilitated communication between people with radio static and Morse Code, effectively cutting through the world’s white noise.

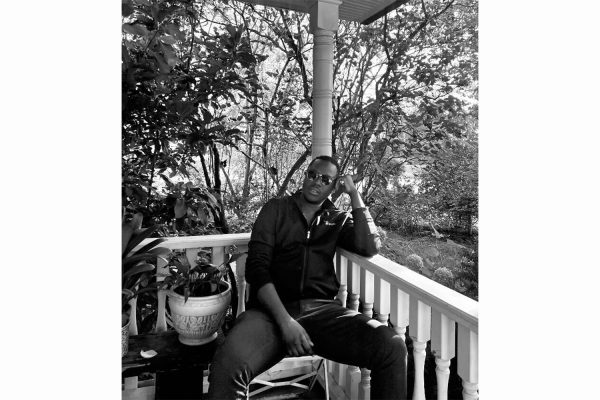

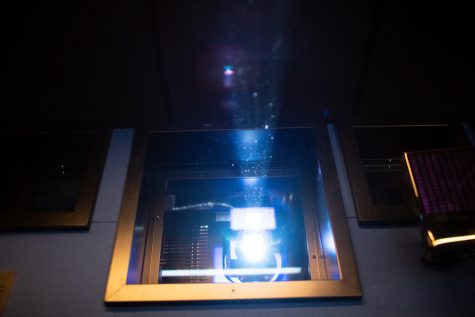

The Space Between exhibit by Edward Kelly is seen in Public Space One North Friday Dec. 2, 2022. The exhibit looks at communication with found objects.

December 5, 2022

Spattered with workshop paint and lit by pillars of sunlight streaming in through the window, a 20-foot table compiled of upcycled furniture spans two rooms on the first floor of Public Space One’s North Gallery on Gilbert Street.

This table is part of the exhibit by Edward Kelley, “The Space Between.” From Nov. 18 to Dec. 3, the exhibit explored communication across literal and metaphorical distances with two pirate radios and International Morse Code.

Edward Kelley is an artist from Des Moines who works as a faculty member and studio technician in the Department of Art and Design at Drake University. He completed his undergraduate degree at the College of Charleston and his graduate degree from Syracuse University.

Kelley works primarily as a sculptor, but his work also focuses on elements of sound and media. Having originally studied anthropology in college, he is inspired to explore different cultural aspects of society with his work.

This particular exhibit is both a sculpture and an interactive piece of art. Visitors are encouraged to engage with it by sitting on opposite sides of the table and sending messages back and forth to each other with the pirate radios. International Morse Code is painted on the table by the radios for visitors to refer to when sending their messages.

What allows this radio correspondence to occur is the spark gap, the first form of airwave transmission that interrupts radio frequency.

Once the radio frequencies are set, visitors can press a button on a piece of upcycled material, either a piece of wood or the top of a leather trombone case. Pressing the button sends a voltage to two steel conductors on the table.

The conductors hold the voltage on one side until it builds up to the point where the conductors are forced together across the narrow space between them, generating blue sparks and an electric buzz that cuts through the constant radio static. The length of time the button is held down translates to either a dot or a dash in International Morse Code.

Kelley typically values participation in his work, but it is especially essential in this exhibit to send a message to audiences.

“I think part of the reason people are important to this piece is to activate it,” Hannah Givler, PS1’s artist resource manager, said. “It’s nothing without participation until you hear or see the spark. It’s more inert. It’s still beautiful to look at but you don’t get to experience the message.”

Kelley chose to approach this form of radio communication after encountering the gallery space. Originally, he had planned to provide the visitors with small pirate radios that they could build themselves, but he decided to change the exhibit to reflect its architectural history.

“So that kind of led to how we communicate,” said Kelley. “And the different aspects of that, especially how we communicate currently and our current kind of situation in the U.S., the lack of communication or the inability to communicate — to kind of add to the use of Morse Code — and how difficult it can be even now amongst family members to communicate with each other.”

PS1 provided Kelley with the gallery space after he applied for an open call to artists, but he also worked with them seven years ago on a different exhibit. He loves the opportunity to work on more abstract pieces with them.

RELATED: Public Space One receives USA Today grant to bring artists of color to Iowa City

“That’s something I’m really interested in, creating these types of spaces for experimental works and experimental artworks to allow artists to do what they want to do without too many restrictions,” Kelley said.

Another important element of this exhibit is sound. The ever-present sound of radio frequency static is like the white noise of life that we can only interrupt with human connection and communication. The interrupting spark is what Givler refers to as “the one point of clarity.”

Three of Kelley’s friends, two of whom are his faculty colleagues at Drake University, loved the visual aspect of the piece and its composition of olden found objects, most of which Kelley found on the side of the road. They also found visitor interaction with the exhibit valuable to expose our inability to communicate.

“I think it’s important that visitors have a tactile relationship with it and see that it’s awkward, even if they don’t understand specifically how to do it,” Phillip Chen, one of Kelley’s colleagues, said. “This belief that it’s awkward is important.”