The art of the scream: How horror has impacted the cinema industry

Despite being around since the beginning of film, horror has remained in a dark corner in terms of cultural importance. A few lovers of horror give their take on the artistic process behind the genre’s dark imagery.

October 3, 2018

Shielded by cozy blankets, a group of friends sit inside a dark living room, deeply invested in a slasher film. As the film progresses, the friends make fun of the cheesy effects and predictable plot.

A “jump scare” occurs.

They gasp in unison, then laugh off their sudden fear.

Suddenly, a gratuitous amount of blood is splattered. They all retreat inside their blankets to avoid the grotesque scene.

Despite being a popular tradition during the Halloween season, horror movies remain critically overlooked in the film industry. Since the Academy Awards began in 1929, only one horror film has won the title of Best Picture: The Silence of the Lambs in 1991.

The top grossing horror film is currently the 2017 remake of It, which has grossed approximately $700 million. That is a long way behind the top-three highest-grossing films of all time, Avatar, Titanic, and Star Wars: The Force Awakens, each of which earned more than $2 billion.

While the genre remains overshadowed, a few individuals want to change the culture of critical thought and cultural acceptance of horror movies.

Hannah Bonner, a film-studies doctoral candidate at the University of Iowa, teaches a course called Film Club, a 1 credit hour class in which students watch a film screening and discuss the content. The fall semester is focused on horror movies.

Bonner said discussing horror movies in a classroom setting can ignite conversations over cultural issues and cultural paranoia among her students. These conversations can lead to dissecting common traits in horror — such as mistreatment of women or the mentally ill — and interpreting what they say about today’s culture.

RELATED: Step inside the Grindhouse

“It seems like horror is really salient in bringing topics people have a lot of opinions about,” Bonner said. “They kind of allow us to enter these conversations in a way that’s entertaining but also provocative and thought-provoking.”

Andrew Owens, a UI lecturer in cinematic arts, focuses much of his academic work on horror movies. In the grand scheme of everything, he said, horror films aim to capture what people commonly fear as a society.

Owens points to a film such as Get Out, directed by Jordan Peele, as an example of a socially conscious horror film, exploring racism as a major plot point.

“Often, we are afraid of things like sexual difference, racial difference, and that very much becomes problematic in horror films,” Owens said. “One of the things that sort of sparks conversation about innovations of horror is when horror does take up those questions head-on rather than making them just an afterthought. That’s what made [Get Out] such a phenomenon. It doesn’t align the question of race, it puts the question of race front and center.”

Owens said he believes horror movies throughout generations reflect a common fear of society during its respective time period. During the ’50s, when alien-invader films were popular, he said, these films were often interpreted as symbolizing fears of the Cold War.

“Any piece of media does not exist in a vacuum,” Owens said. “Everything exists in a cultural context. Whether it be conscious or unconscious, we are all influenced by the world we live in.”

Bonner said she was particularly interested by Unfriended, a 2015 film directed by Levan Gabriadze. The movie depicts a group of high-school students haunted by their deceased classmate through Skype, being told through a Macbook screencast. She believes the movie captivates people because of the increasing recent fear of the internet and social media.

“It’s a film a lot of academics are fascinated by because the film is calling attention to the interface of the screen and the progression in technology,” Bonner said.

Outside of academia, working in horror brings a different kind of appeal for filmmakers.

Mike Saunders is one of the co-creators of Halloweenpalooza, the only horror-film festival in Iowa. Based in Ottumwa, the festival began in 2010; it will start Oct. 12-13 this year.

Art is supposed to make you think. I think this applies — no more, no less — to horror.

— Andrew Owens

Saunders said the idea grew from him and his like-minded friends, and they began the event as a party. Afterwards, he said, interest grew in the community and transformed into a festival for anyone with a interest in the event.

Saunders creates his own movies, primarily specializing in horror. Working in the genre gives him the chance to explore several themes, he said, whether it’s making a realistic story portraying a serial killer or a fantastical setting inhabited by monsters.

“As a filmmaker, I find it a very liberating genre where you can go many different directions,” Saunders said.

One of the more difficult aspects in creating a horror film is getting an explicit reaction from the audience, he said, because the goal is to make the audience members visibly afraid.

“There’s an open response that clues you in whether or not you’re doing a good job,” Saunders said. “It’s not easy, especially in this day and age, to get that response.”

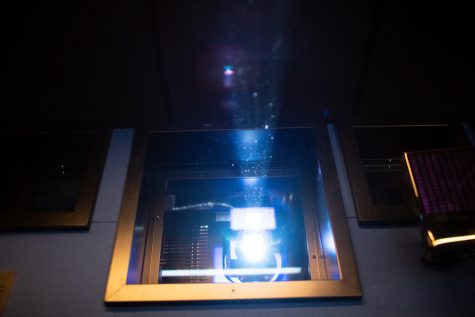

Ross Meyer, the head projectionist and facilities manager for FilmScene, hosts Late Shift at the Grindhouse, in which the cinema presents horror films every Wednesday during late hours. Believing that horror-movie screenings are placed on the sidelines in FilmScene, Meyer said, he thinks the series teaches the audience that the genre is important.

When it comes to themes related to the supernatural, he said, horror movies can scare people beyond the surface of the content.

“Because so much of the world is a believer in the supernatural and religious deities, it lends those films a certain amount of power,” he said. “A movie such as The Exorcist gains power that necessarily didn’t even exist on page, but when it hits the screen, it gives the film more than the sum of its parts.”

Some horror films have been innovative for cinema as a whole, Meyer said, such as Night of the Living Dead, directed by George Romero (1968). Being ahead of the curve, it was one of the few films in the 1960s to cast a black lead. The film also revolutionized how zombies were portrayed in media, making them appear as flesh-eating cannibals. Before the film’s release, zombies were typically depicted as nonthreatening, undead beings.

“[Romero] and his team created an entire genre of film,” Meyer said. “So much of modern filming would be different if Night of the Living Dead didn’t exist.”

Although Owens acknowledges that many people feel reluctant to watch horror, he said, the experience can be enlightening in terms of confronting fears.

“Horror is certainly one of the genres in which people approach it with a massive set of assumptions,” he said. “The better horror movies disrupt those expectations. I think there is value in the fact art isn’t supposed to be comfortable. Art is supposed to make you think. I think this applies — no more, no less — to horror.”