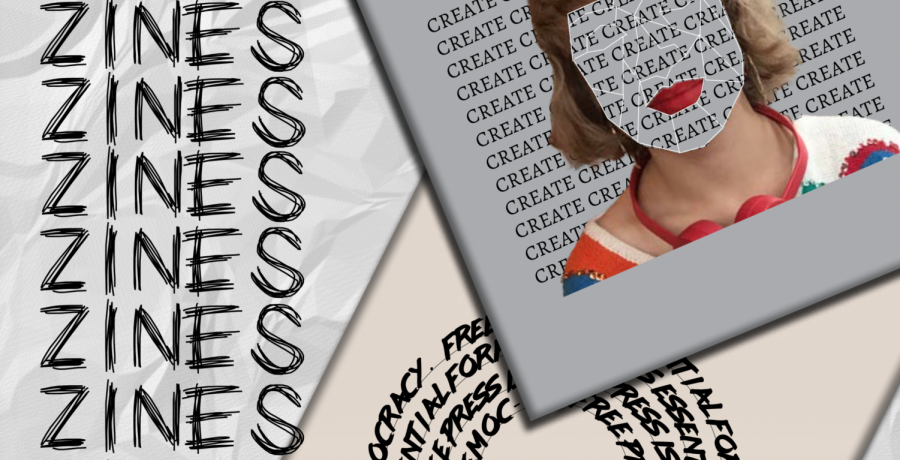

Zine scene: giving voice to any and all artists

Since the ’90s, small, self-produced anthologies of writing and art called zines have given the young, impassioned, and atypical voices in Iowa City a chance to be heard.

August 23, 2018

Iowa City is home to literary giants whose names grace the shelves of Prairie Lights and whose faces pass discreetly by en route to Dey House. But the City of Literature, in all its grandeur, has also always been a hotbed for underground art.

“Zines have always been a staple of counterculture,” Molly Bagnall said. “The whole point is not to edit things or reject things but just to give local artists and creators the chance to have their work published in some sense, no matter how small scale it is.”

Bagnall is in the process of coproducing her fourth zine since February. Each small, self-bound zine has had a theme: the first that all submissions were 33 words or fewer, the second interpreted family and home, and the third considered the body. Yet even those umbrellas act only as an usher, an invitation to get the artistic gears going, with the promise to publish whatever the result may be.

“If they submit it, we put it in,” Bagnall said.

Mental Floss dates the first zines back to the 1930s, where the sci-fi scene in Chicago started a tradition of producing fanzines that lives on today. Defined by their local circulation, low cost, and self-publication, zines took off in other communities. Punk zines became incredibly popular in the ’70s, when copy shops made it easier than ever to mass-produce the publications. Today, zines reign in the underground art and music scenes of New York, London, and LA, and they have even been produced by big names such as Kanye West.

Facebook and Twitter have been the breeding ground for Bagnall’s passion projects, connecting her with local students and artists who would like to be published. One such person, UI senior Becca Bright, turned out to be the source for the next zine’s theme.

When Bright was facing a debilitating dose of writer’s block last year, she turned to her camera. Photography was an old hobby, and she decided to look through the lens again just to gain a different perspective. What began as photo shoots with friends quickly evolved in to something more.

Because of an initial coincidence, her models were all queer women, and the act of standing up to the camera seemed to empower them to reflect on the ways we can redefine femininity and beauty.

Playing with the idea of being “seen,” Bright began using the hashtag #icwomen to promote the diverse faces of queerness in Iowa City.

Bagnall was one of Bright’s models, and together, they decided that the fourth zine should give voices to the queer faces of #icwomen and encourage others to join in conversation.

“A handful of the girls are creative writing majors or artists,” Bright said. “So I think because they had already put themselves out there in a creative way by having their photos taken, they had the same sort of eagerness to actually write something out.”

Like a diary or looking at a photo of yourself, Bright believes that the worth of a zine is that it gives artists a place to reflect.

“With a magazine, the writer or whoever has to give to the magazine,” she said. “But I feel like with a zine, the zine almost gives to the contributors.”

Zines can be found stacked happily in White Rabbit, Prairie Lights, the Record Collective, High Ground, the Haunted Bookshop, and the Iowa City Public Library — free (or close to it) for whoever needs a read.

I don’t know if there’s a zine community — but there is a zine for every community.

— Molly Bagnall

The unimposing relationship among artists, businesses, and locals is definitive of the joyous and collaborative concept behind producing a zine.

Maggie Timboe, a recent transfer student to the UI, said zine culture was one of the first things she heard about at Orientation, after mentioning her interest in publishing to a university librarian.

“I think zines are a good way for people to express things that they’re really passionate about that other people might find really niche or a little geeky,” she said.

During her first weeks in Iowa City, Timboe will be buried in Special Collections of the Main Library, enacting her geekiness by digging through a curated collection of culinary zines to help inspire her own. Her foodie publication will combine her love for history and English by republishing archived recipes from the diaries of old farm women, bringing them back to life alongside today’s voices.

“I think a recipe is a really universal thing that people can use and look at, but I think a lot of zines are really for the people creating it,” Timboe said. “I don’t really have a theme for the first issue. I want people to write or take pictures of whatever it is about food that they find most important or whatever has affected them the most.”

While Bagnall’s attraction to zines is for their innate artistic energy, their collaborative quality, and the counterculture that they represent, Timboe is the proof that a zine truly can be anything that the creators want.

In a small paper pamphlet, bound by hand, her fascination with food has as much validity as Bright’s project to make queer women feel empowered, and Bangall’s love for art is as well represented as another’s passion for politics.

As Bagnall put it: “I don’t know if there’s a zine community — but there is a zine for every community.”