The Koch Brothers. Politico. John Stewart. The New York Times. And the city of Coralville.

Tax-increment financing, known locally and nationally as TIF, is public financing that freezes a property-tax base in an area.

When Coralville’s investment in TIF helped spawn the city’s debt, the national entities started paying attention.

And so, when the November 2013 elections rolled around, a lot of eyes were on Iowa City’s neighbor to the west, wondering how a city of this size, in the middle of small-town America, could amass this kind of public debt and create such an unbalanced financial footing.

But even with the national eyes on the city and its Super PAC donors, none of the candidates who publicly spoke out against TIF use were elected.

Incumbent City Councilor John Lundell — a TIF supporter — triumphed the city’s mayor race with 65 percent of the votes, while two incumbent councilors and one challenger who backed tax-increment financing were elected.

Iowa had taken notice a full year earlier, and the Legislature implemented TIF reforms beginning in 2013.

Further efforts to reform the controversial public-financing method in the state may have died in the Legislature last month, but a handful of local elected officials, state lawmakers, and a university economist say the fight is far from finished.

Leaders from both sides of the political aisle remain torn over TIF’s use and effectiveness.

Those subsidies are often utilized for redevelopment, infrastructure improvements, and other community-oriented projects. Under TIF, the would-be property-tax revenue from projects is absorbed by cities, who often then turn around and usher in new development projects.

The recent action in Des Moines — in which lawmakers debated specific ways in which the controversial public-financing tool may be used — comes amid heightened local and national media attention and the construction of gleaming high-rise towers, sprawling suburban shopping areas, and corporate data centers in many pockets of the Hawkeye State.

While Iowa communities large and small — including Des Moines, Iowa City, Cedar Rapids, Coralville, and Swisher use TIF — much of the attention from residents, lawmakers, and development officials has zeroed in on Iowa’s urban and fast-developing areas.

Coralville: TIF use is responsible

In Coralville — a community of roughly 20,000 residents — the tool and the number of TIF districts the city manages often served as ground zero during recent City Council elections and community meetings.

By Iowa law, cities are allowed to have numerous TIF districts.

Today, 51 percent of the city’s outstanding debt is tied up in the 180-acre Iowa River Landing development and the city-owned Marriott Hotel and Conference Center, city documents show. The notion of TIF districts throughout Coralville have been in place since 1996 and have pushed its property-tax base up by more than $836 million.

Iowa City: Officials call TIF use transparent, conservative, and project-based

While the concept of TIF has been floating around the nation for decades, Iowa City chose not to implement it until 2000.

Since then, the Iowa City City Council has issued more than $16 million in tax increment-financing, according to city records. Sycamore Mall was the first to benefit from the special financing. The East Side mall, now named the Iowa City Marketplace and under new ownership, was struggling with an aging appearance and was bleeding retail and restaurant tenants.

That project was given $2 million in public money to improve the existing mall, retain what was then the 40,000-square-foot anchor store Von Maur, and “maintain or exceed occupancy minimums,” according to city records obtained by the DI. Subsequent city records indicate that $7.1 million in building permits were issued for that project. When completed, the shopping center saw a 222 percent increase in property value.

Since then, officials have used TIF financing to expand the city’s Mercer Park Aquatic Center, to grow operations at two plastic-manufacturing facilities, aid in the construction of two downtown high-rises, redevelop two additional East Side shopping areas, rehabilitate a historic downtown building that until recently housed a shuttered bar, and grow the headquarters for the leading U.S. independent national distributor of natural, organic, and specialty foods.

But of all the projects, the council has mostly come under fire for shoveling out millions in financial incentives to a downtown developer who has invested millions of dollars in the city’s core.

Marc Moen, an owner of the Moen Group, has faced steep criticism after receiving TIF from the city for some new high-rise construction projects and historic-preservation efforts in downtown.

But city officials who have supported him point to Moen’s vast development experience as well as the jobs he’s provided for the community.

Mayor Matt Hayek — a two-term Iowa City mayor who has been a long proponent of Moen-led projects — failed to return requests for comment as of Sunday afternoon.

But he has spoken publicly in favor of the financing — such as for the construction of Park@201 during a July 10, 2012, meeting, the DI has previously reported.

A TIF deal is being negotiated with city officials and the group for the proposed 20-story high-rise, the Chauncey, Moen wrote in an email on April 18.

Critics have said Moen’s large glass-clad buildings don’t fit the character of downtown. However, supporters have said the developments meet niches previously underutilized downtown, including high-end housing, grocery options, Class-A office space, and added retail opportunities.

“It is a fact that Park@201 would not have been possible without the TIF, and we could not construct that project without the assistance,” Moen wrote in an email. According to city documents, the city of Iowa City has allocated $8.75 million in TIF for Moen’s projects.

Park@201, which will cost at least $10.7 million, will be home to roughly 100 employees of the building’s respective tenants. That is on top of hundreds of employees at the Plaza Towers and the several dozen other employees at other Moen-owned buildings, Moen said.

Without the boosts in TIF over the years, downtown would not have Plaza Towers or the presence of FilmScene and Modus Engineering. The Packing and Provision Building, 118 E. College St., would not have been renovated to the extent it was nor have the facilities that are housed there, and Park@201 would still be a one-story concrete block building, Moen’s email said.

ISU economist: ‘It isn’t economic development’

Staunch opponents of public-financed development incentives, including one economist, say Iowa is awash with TIF growth, and its negative effects are widespread.

David Swenson, an economist at Iowa State University, dispels contentions often championed by city councils and developers that TIF translates into economic development.

“It isn’t economic development,” said Swenson, a published TIF critic who has been studying the practice for approximately 20 years.

That said, he notes legitimate TIF use can and does work, and he pointed to Des Moines’s extensive downtown overhaul that was fed in large part with TIF funding.

But. Swenson says he can’t support, say, Coralville’s massive dependency on TIF.

“[TIF allocations] are used much too promiscuously from people who don’t understand them; Coralville is a prime example,” he said. “[Coralville officials have] abused the public’s trust because of their use of the TIF law.”

TIF impact and use in Johnson County

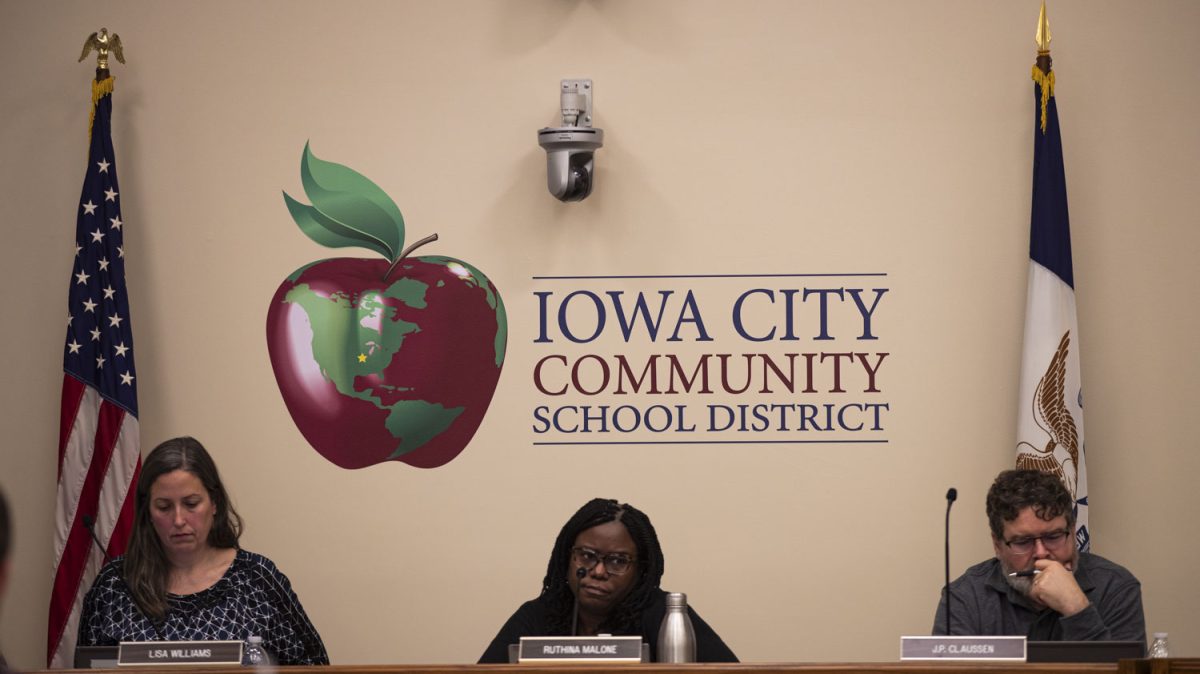

Many members of the governing body of Johnson County, the Board of Supervisors, have been staunch critics of TIF use by local municipalities, saying it damages the county’s budget, the funding of area school districts, and taxpayers.

Currently, nine of the 12 towns in Johnson County have 19 tax-increment financing urban-renewal areas, county Deputy Auditor Mark Kistler told the supervisors on Feb. 25.

University Heights and Hills are two Johnson County towns that have opted out of using the tool, he reported.

According to the minutes from the February meeting, Kistler described how TIF works and noted that Coral Ridge Mall is an example of how TIF negatively affects the county’s tax revenue.

Approximately $5.1 million of TIF appropriations will be diverted from Johnson County in fiscal 2015, which starts July 1, he said.

In a recent email to the DI, Kistler noted that because more bonds for projects took place this year, $4.6 million in revenue will be diverted from the county.

Despite being the fourth-most populous county in Iowa, Johnson only trails Polk County — home of the quickly developing Des Moines area — in largest uses of TIF at nearly $2 billion, Kistler said.

TIF revenue is expected to eclipse $27.1 million in fiscal 2015, Kistler said.

But not all are in favor of adding to that number.

Supervisor Chairman Terrence Neuzil — a supporter of TIF — said the county would never use the tool, even for a proposed $30.8 million annexation to the 1901-era courthouse. Supervisors are aiming to put a courthouse annexation on the upcoming November ballot.

Rather, Neuzil said, it should be applied minimally when it comes to housing and purchases of public buildings, and Johnson County and officials from local school districts ought to be able to say yes or no to expansion of TIF.

In April, Neuzil scrutinized the city of Coralville’s use of TIF, specifically the Coral Ridge Mall’s 20-year TIF district.

That TIF area is set to expire in 2018. Neuzil attributed that city’s bloated financial standings to the $278 million in outstanding debt the city owes as of June 30.

One “valid” TIF use, he noted, would be for Iowa City’s Riverfront Crossings District, a nearly 280-acre zone south of downtown.

Dubbing that area a “tired entryway into the city,” Neuzil said he was unsure how much should be allocated to redevelop that swath of land.

In the most recent interview with the DI, Neuzil emphasized continuing TIF reform.

“There needs to be certainly some additional limitations so that cities aren’t taking 60 to 90 percent of their entire community and putting it in a TIF district,” he said.

Much of the blame lies in the hands of Gov. Terry Branstad and the current legislative leaders in the state, he said.

“We have a bit of an every-government-for-itself mentality, and it has been really just expanded by the Legislature tightening the grip of our local tax base,” he said. “When the governor and Legislature reduce commercial property taxes, it means that every government is trying to find a new source of funding,” leading it many times to TIF.

Without fixes to the state’s TIF laws, county governments are going to be affected the most.

Issue not divided by party lines

Rep. Tom Sands, R-Wapello, said he has had several conversations with Branstad over TIF use, but, like others, he believes the ultimate responsibility falls on the Legislature for finding a fair path.

Sands said he believes there is support in the House to pass a new bill to the Senate. He said it may be drafted and presented during the first month of the new session, which begins in January. Sands, who represents House District 88, which runs from Muscatine County through Des Moines County in southeastern Iowa, said in recent years he has witnessed TIF use expand to build libraries, swimming pools, and city halls.

For him, the question of TIF legitimacy comes down to simply who is forced to front the eventual bill for the projects subsidized with the incentive.

“It’s who has to pay, and if people in northwest Iowa are asked to pay for a swimming pool in southeast Iowa, there is nothing remotely fair about that,” he said.

Rep. Sally Stutsman, D-Riverside, who serves on the Senate Ways and Means Committee, said even though she doesn’t see TIF talks moving forward this year, modifications are needed.

“I think that the problems we’re getting into is we’re seeing communities continue to push the envelope on the use of TIF,” she said, noting that it is an “increased burden on taxpayers.”

Stutsman — who said she is not opposed to TIF use in certain cases — believes the only way it can be modified is with new legislation and support from the Branstad administration. Increased news coverage that has arisen from local and national news outlets is also helping to keep discussions moving, she said.

“I don’t think the original people who wrote the [idea of] TIF thought it would be used for high-end housing or in areas where there isn’t blight,” she said, praising Sands’ bipartisan commitment and cooperation in wanting to see change take place. “The more we talk about it, the more the average taxpayer can understand what it is.”

Tensions between Iowa City and Coralville officials continue as the cities differ on TIF use

Iowa City City Councilor Jim Throgmorton was bullish in his general opposition to TIF. He noted that a number of TIF-funded projects should not have passed the council during the years he has served.

Today, ones that achieve high levels of energy efficiency, especially with regard to carbon emissions are deserving of it, he said.

“I don’t like TIF. In my ideal world, not a single entity would receive TIF,” he said. “But we don’t live in an ideal world, and I am willing to support particular projects that meet particular objectives. We’re better than our neighbor in how we’ve been using it.”

New policies for TIF could and should be done by the Legislature, Throgmorton said, because cities are so constrained by current state government regulations about the economic-development tools they can have at their disposal.

While quick to decry the excessive use of TIF by Coralville, Throgmorton maintained that there is not enough clarity over what defines “public good” — a reason for issuing funding for TIF — in the city.

Throgmorton said he would like to see public financial assistance used in some fashion — possibly another TIF plan — to rejuvenate the Lower Muscatine Road/First Avenue commercial corridor on the city’s East Side. That area includes the Iowa City Marketplace that Throgmorton said could better tie with the Tait Alternative High School, Kirkwood Community College, Southeast Junior High, and the Twain Elementary neighborhood.

“TIF is a complicated beast,” he said.

Iowa City City Manager Tom Markus said the city was among the backers of the 2012 reforms and supported the most recent legislation.

The more aggressive surrounding communities support tax-increment financing, he said, and that pushes cities to fight back with its use.

Comfortable with what he sees as the “conservative” approach the city of Iowa City has taken with TIF, Dennis Bockenstedt, who serves as the city’s finance director, said city staff had looked over the provisions to the newest TIF reform bill. Because one portion of the now defunct bill called for a limit on the life a TIF district can have, he said, the city’s use of the tool would not have been affected.

Although the city is in the process of developing a TIF area for a 170-acre parcel on the Northeast Side known as the Moss Ridge Campus office park, Bockenstedt said, he is unsure whether officials will increase or decrease the use of the tool in the coming years.

The Moen Group’s 14-story Plaza Towers stands as a symbol of good use of TIF, Bockenstedt said, because the $22.2 million project has added around $35 million to the city’s tax base since opening in 2006.

Wendy Ford, the economic-development coordinator for the city, said the city’s three-step process of approving TIF funding is separate and different from the state’s. The policies that were updated on April 15 are the only written and public documents regarding a city in Iowa’s guidelines on how TIF is granted, she said.

While TIF captures the majority of the economic-development spotlight in Iowa for funding, Ford noted that rebates, and the use of bonds, are also at the disposal of communities.

Despite having made national headlines for their eager pursuit of TIF, Coralville officials remain unapologetic.

Tony Roetlin, Coralville’s finance director, continually defended the community’s TIF use, emphasizing that city officials have used it responsibly. He questioned whether more legislative actions and restrictions on TIF use would contribute any meaningful help.

“If the city didn’t believe it wasn’t effective, the city wouldn’t do it,” Roetlin said.

Retail sales in the community of roughly 20,000 residents have grown from fewer than $200 million in 1997 to close to $700 million in 2011, the most recent year of recorded data, Roetlin said. He said much of that growth can be attributed to the aid of TIF.

On Jan. 7, 2013, Coralville city officials published documents on the city’s website regarding TIF in order to become more transparent, Roetlin said. Still, he said, the website does not offer enough transparency, and the hiring of a TIF transparency officer is a “thoughtful suggestion.”

Swenson, the Iowa State University economist, says despite many attempts to rein in TIFs by Iowa lawmakers, restructuring in the short-term is unlikely.

“The economic-development community exerts a tremendous amount of power over the Legislature, and they will prevent any meaningful reform here in the state,” he said. “[TIF] shifts the costs of government. It’s turning into nothing but a great big industrial and commercial giveaway.”