A man wakes up around 5 a.m. to turn on the coffeemaker and get on the Internet. He surfs the web, flips through the channels on the TV, and has his first cup of coffee for the day.

This is the morning routine for 33-year-old Phil Steffensmeier, a lifelong citizen of Iowa City who is currently unemployed — in large part because, as do 1 percent of the world’s people, he suffers from bipolar disorder.

Mental illness can be hard to diagnose, and sometimes as a result, patients initially receive incorrect diagnoses. Local psychiatrist Christopher Okiishi said that over time, methods of diagnosing mental illness have not really changed. The method doctors use is a patient interview detailing her or his life and medical history.

Phil was one person who began with a different diagnosis than he has today.

At age 15, he was initially diagnosed with major depressive disorder, a condition, he says now, that left him suicidal. The diagnosis stuck throughout his teenage years. But when he began studying at Luther College, things changed.

“I started feeling very weird — very weird,” he said. Phil believed his moods were changing severely and thought it may be a sign of depression, but at the same time, he knew he was not depressed and didn’t understand what was happening.

When Phil went to his academic adviser, the adviser was unsure what to do to help. He left his dorm room and headed home to Iowa City to his parents’ house, where things got worse.

“When I was home, that’s when I had my first full-blown manic episode, and that required hospitalization,” he said. “I was awake for a week straight.”

When he experienced that first manic episode, he said, his behavior was “inexplicable.” His illness even prompted him to break into City High.

“All I wanted to do was go exercise,” he said. “I thought it was a public building, and therefore, it ought to be open to the public. It did not occur to me that it [was] a Sunday morning and I, a former student, had no right to be there whatsoever. At the time, it just totally made sense to me.”

He has been struggling with trying to identify what his actions should be classified as. He doesn’t believe they are illogical, but they are irrational.

“There’s an underlying logic to everything I do,” he said. “The problem is that logic is flawed. I take things that are not truths, and I accept them as truths.”

Medicating Phil’s illness has not been easy; he’s been through approximately 40 different psychiatric medications. Although he fully follows his medications, he still hasn’t found a panacea: something that negates the mood swings entirely.

“The medication is not just a ‘cure-all,’ ” he said.

Phil has experienced a number of side effects with medications — weight gains, tremors and shakes, anxiety, extreme sedation, dry mouth and eyes, impotence under one drug, stomach discomfort, withdrawal if not taken on time, mania, elevated risk of seizures, and even extreme sensitivity to grapefruit.

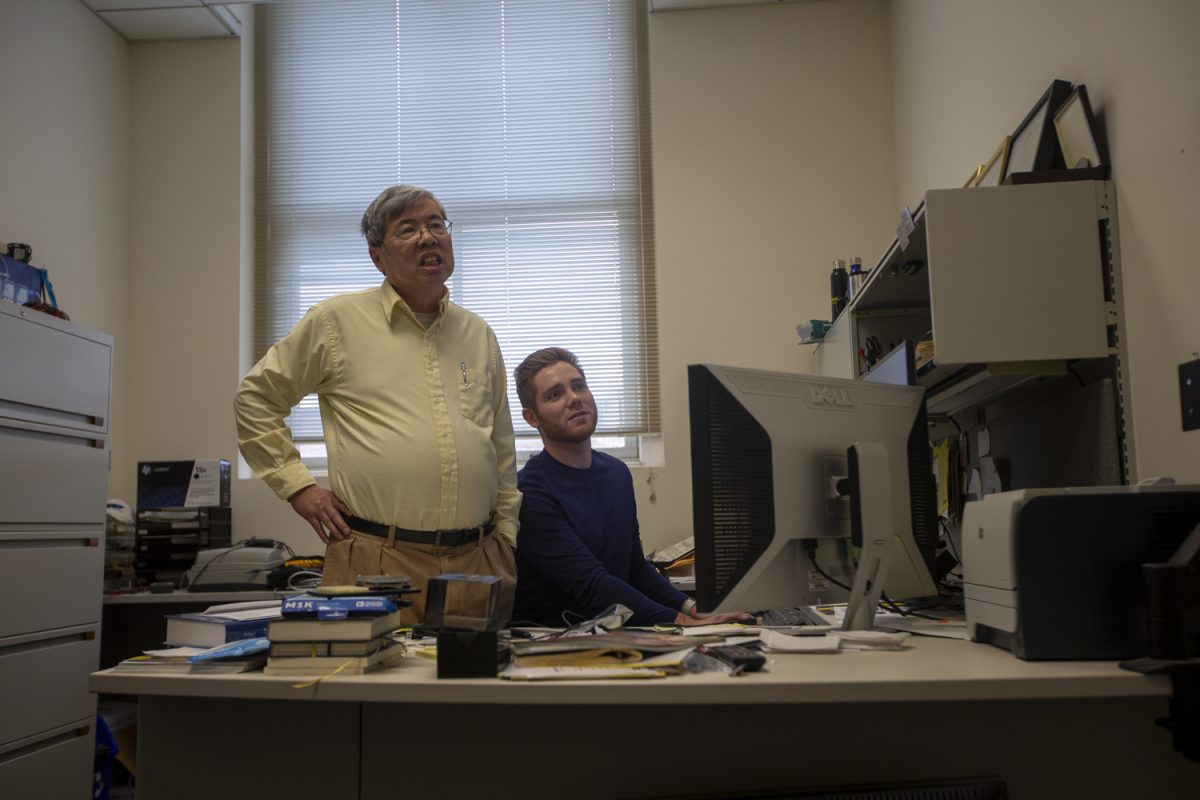

Jess Fiedorowicz, a University of Iowa associate professor of psychiatry whose specialty is bipolar disorder, said trying to find the right medicine for patients is often a trial-and-error process. He said doctors are working to combat this in a variety of ways.

“One direction is trying to better classify these conditions,” he said. “If we can identify subtypes … and clearly defined subgroups, we can develop better treatment.”

In battling his mental illness, Phil has become a large contributor to the National Alliance on Mental Illness of Johnson County. He serves on the organization’s board, and he surpassed $1,000 in fundraising for the group’s annual walk, which took place April 26.

One piece of hope for those who suffer from bipolar disorder is increasing their daily routines and self-discipline. Fiedorowicz said social-rhythm therapy, which encourages just that, has proved to work in the prevention of episodes.

Phil managed to find a unique way that helped him with those struggles — his dog, Mikey.

“Things were a lot easier when I had a dog,” he said. “It was something to get up for in the morning. It gave me a set time I had to come home to feed him dinner, and it allowed me time for myself to eat dinner.”

Mikey passed away at the end of last year. That was hard for Phil, because Mikey, a bichon-poodle mix, helped to keep him on a schedule.

This summer, Phil plans to adopt a dog from an animal shelter.

Although he is unemployed, he has held a dozen or so jobs. He’s worked for a debt-collection agency, a vacuum-cleaner repair shop, hardware stores, a gas station, a concrete factory, and a moving company. In college, he did lights and sound for the Theater Department.

But because of the perfectionism, guilt, and depression his illness has caused, he was unable to keep a job for long. He has been on disability for five years, but he hopes for this to change soon.

“I’ve been looking at jobs at Goodwill,” he said. “I would really like to get involved with that organization. I believe strongly in their mission. They do an exceptional job of employing disabled people. I haven’t given up on working, [and] I don’t think I’ll ever give up on working.”

In terms of schooling, Phil is about halfway done with five different degrees: biology, chemistry, economics, finance, and accounting. He spent two years at the University of Iowa, a year and a half at Kirkwood Community College, and two and a half years at Luther College, in Decorah, Iowa.

He has more than enough credits to graduate, but he was never able to finish a degree.

“I went into school with three different majors,” he said. “I’ve added a couple of majors since then. In retrospect, that was probably hypomanic. No one told me you can’t do that.”

At Luther College, in 1999, Phil met Shawn Gumm, who is now one of his close friends. Shawn, now a UI student studying international business, said that after not finishing his degree at Luther, he took time off to travel, and with more knowledge of what he wanted to do, decided to attend the UI.

“It became clear that something was going on with [Phil],” he said. “I don’t think I really articulated what it was as his friend until sometime later.”

Gumm now meets with him for dinner, drinks, or good conversation at least once a week. Gumm also plays Scrabble with Phil — a game Phil’s won countless times.

“I try to play against him,” Gumm said. “He’s quite the Scrabble champion.”

Although Phil thinks society has a long way to go in being accepting of mental illnesses, he is thankful to live in Iowa City, where, he said, the care needed for mental illness is up to par.

“Johnson County has the resources, the commitment, and a general caring; that’s really not available in other places in this state,” he said.

A 2013 Iowa Department of Public Health Mental Health and Disabilities report stated that 89 of Iowa’s 99 counties suffer a health manpower shortage, or as Okiishi says, “federally underserved,” in terms of psychiatrists. Because mental health is funded at the county level, where you live can truly affect the care you receive.

“You can move literally two blocks away, and you’re in a different county, and now your services are completely different,” he said.

Phil, like many others who battle mental illness, works every day to break down the stigmas associated with it. He wants people to see him as a person, not an illness.

“The biggest thing I want people to know is that they don’t have to be afraid of me,” he said. “Just because I have a mental illness doesn’t mean that I’m going to hurt anybody. It just means that I have trouble with everyday life.”

In five years, Phil said, he will still contribute on the local National Alliance on Mental Illness board, and he hopes that he will have a job.

“I know I don’t have a job, and I don’t get all of the things done that a lot of people do, but I’m really trying to make a positive impact,” he said. “So that’s how I see myself in five years — still spreading the word, still trying to erase that stigma, and just soldiering on.”