Who are those angel-head hipsters?

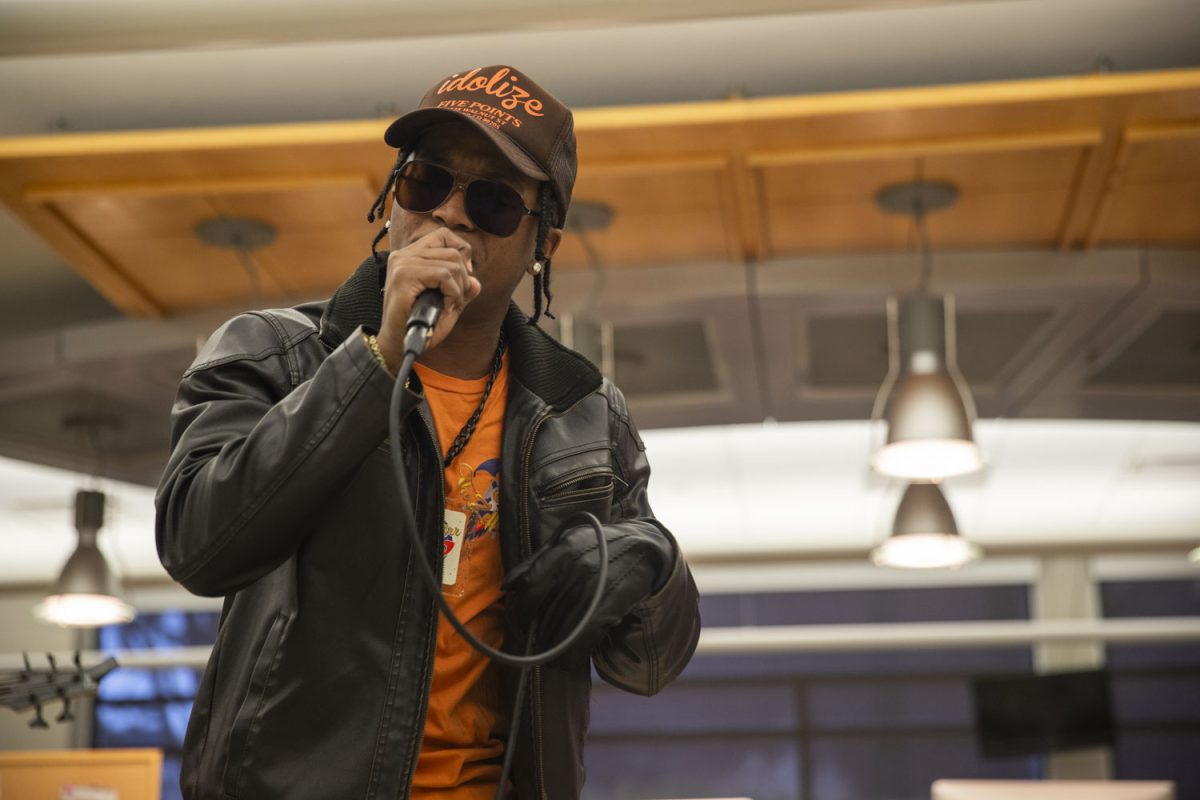

They gather together at a dimly lit underground club, watching as poet Allen Ginsberg reads from his controversial poem, “Howl.” The audience members listen intently as his voice fills the tightly packed room. Occasionally inhaling cigarettes, they do not look shocked by references to sex, drugs, and smooth, smooth jazz.

I began watching Howl expecting to learn about the life of Ginsberg. However, this is not a story about the poet but about the outcome of his work. The film focuses on the “Howl” Trial of 1957, which started when the San Francisco police confiscated copies of the poet’s narrative poem.

Professors and authors speak one by one, debating whether the poem has any literary merit.

Because of this, I was left with unanswered questions about Ginsberg. Throughout the film, he talks about how he wanted to please his father, who was a poet as well. Nothing more is said about his family, except that his mother was sent to a mental institution. The reason? We’ll need another movie.

Ginsberg checks into a mental clinic. He cannot feel comfortable in a society that deems homosexuality as immoral. He is finally let out months later on one condition: He must live as a straight man.

His pain is etched in his poetry. With each reading of “Howl,” the story transforms from a French New Wave feel to graphic animation. While some may find the cartoons as beautifully depicting the chaos rummaging through Ginsberg’s mind, it lowered my judgment. Eerie illustrations of heroin addicts, childbirth, and human sacrifices caught me off guard.

This film is composed of layers upon layers: a black and white composition to depict the past, color to show the present day, and animation to illustrate Ginsberg’s poems. Likewise, the film shows diverse layers of the poet himself: a man questioning his sexual identity, a calm and secure adult, and an eccentric poet.

Before viewing Howl, I was skeptical about Franco playing Ginsberg. Sure, he was great as a supporting actor in Milk, Spider-Man, and Pineapple Express, but could this pretty boy handle a leading role? Franco surprised me in his interpretation of Ginsberg. In the poetry readings, his voice is hollow and strong; I felt almost uncomfortable listening to his speech while he described Ginsberg’s explicit thoughts. He switches to a more subdued persona during Ginsberg’s occasional present-day commentaries on the poem. The wide range of personalities Franco exhibits demonstrates he is a well-rounded actor.

Fans of the 1950s Beat Generation will have a greater appreciation for this film than those unfamiliar with it. As a fan of Jack Kerouac, I found it particularly interesting to see Ginsberg’s perspective of the author. In the film, he admits Kerouac was the first person he could truly open up to. It suggests that he was deeply in love with Kerouac and his romantic way with words and, to Ginsberg’s dismay, women.

When describing his writing, Ginsberg says it is like a photograph developing slowly. Howl’s audiences will discover that, like his poems, it takes time to decipher who Ginsberg was. But the acting and setting of New York during one of its most exciting literary periods are certainly worth watching.