Opinion: Endorsements are a poor measure of political success

Horse-race coverage doesn’t account for nuances and shortcomings of the metric.

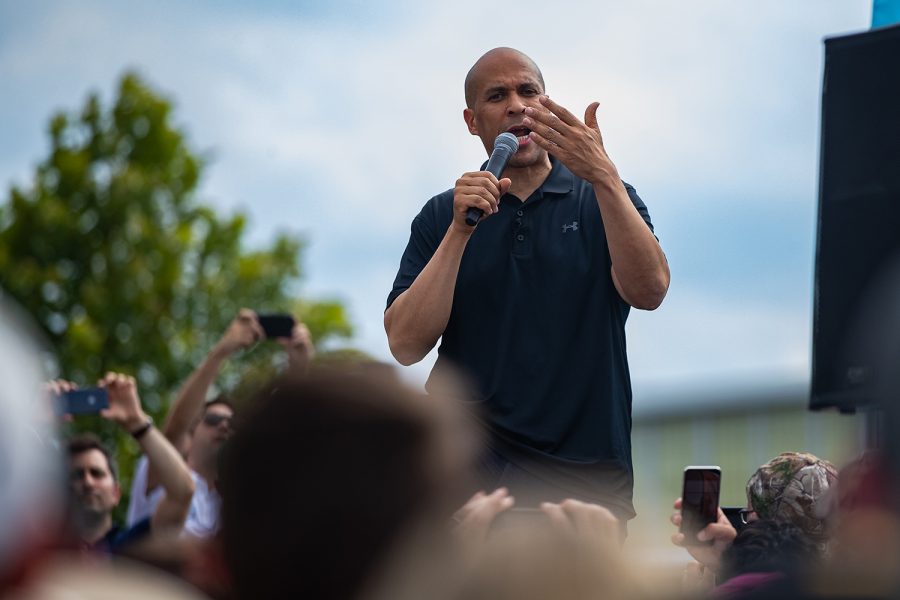

Sen. Cory Booker, D-NJ, speaks at the Des Moines Register Political Soapbox during the Iowa State Fair in Des Moines, IA on Saturday, August 10, 2019.

October 15, 2019

2020 candidates have taken to announcing their endorsements in huge batches, sometimes a hundred names at a time, and political news coverage is eating this trend up. Endorsement counts have become a “horse race,” where number counts and the sheer volume of names in favor of this candidate or that is the nexus of attention.

Lots of media attention (even from The Daily Iowan) is given to these endorsements. While this trend might be interesting, it doesn’t generate the most accurate picture of the candidates’ ground games.

Endorsements don’t work like other political stats

For one, endorsements make for a bad horse race because they are more useful as qualitative than quantitative data. For example, the endorsement of popular and like-minded interest groups sucha as the NAACP to a Democrat would carry a lot of sway among that group’s members but wouldn’t persuade other party members or moderates. In comparison, the endorsements of some 30 Democratic city council seats in the U.S. would hardly make the evening news.

Empirically, endorsements only seem to matter as much as the endorser works to make them matter. A public official might make calls to their constituents to get out the vote and help organize grassroots momentum for their candidate of choice once their endorsement goes public. They also might do literally nothing.

Such disparities make endorsement tallies almost meaningless. It doesn’t matter if a candidate is winning 30:1; it matters which of those candidates are actually working to support their nominee.

Endorsers don’t fluctuate like other indicators because once they’re made, they can’t really be taken back. Endorsements tend to stick with a candidate for the duration of their campaign. The best political data show which meausure of candidate support fluctuates telling observers not only how support has grown and fallen over time.

Public opinion polls and press coverage are two such indicators. They go up and down based on candidate popularity, and thus paint a more telling picture of how well a candidate is doing. The inability of campaign backers to change their mind like the public does means endorsement horse-races struggle to accurately convey actual voter support.

Endorsements have a weak effect on voters

Even when a high-brow endorsement comes along, the people associated with it don’t necessarily follow their leaders. Labor unions can back whoever they please: it won’t change the minds of die-hard, candidate-specific voters such as “Bernie Bros.”

A fundamental problem with endorsements is that the only people who notice the details are those already highly engaged in the political process. These people tend to already have opinions that would resist change regardless of which candidates have which endorsements.

The problem is that recommendations, whoever they come from, aren’t reasons in and of themselves to vote for a candidate. People vote for policies and for personalities, neither of which are conveyed by endorsement counts. Americans in particular have a sense of independence that prioritizes what they think is right over what those around them think.

Research reveals one instance in which endorsements consistently matter to potential voters: those of their peers. According to Morning Consult, Independents, Democrats, and Republicans are more influenced by the opinions of their spouses than any one public official.

People, by and large, engage with politics on a scale smaller than endorsement totals can perceive, and by failing to account for this, the horse-race mentality of these counts is ultimately meaningless. This approach fails to answer a fundamental question of politics, and that question is “who cares?”

Columns reflect the opinions of the authors and are not necessarily those of the Editorial Board, The Daily Iowan, or other organizations in which the author may be involved.