The Canadian government decided to shut down an Ontario nuclear plan in late May because of leaks in the piping. It catalyzed a shortage of a key element used in medical tests, an effect that has hit hospitals around the world — again.

A similar shortage of the isotope called technetium-99m in 2007 forced the UI nuclear medicine department to shut down many of its services. The number of patient visits dropped from 20 to 30 a day to around half a dozen.

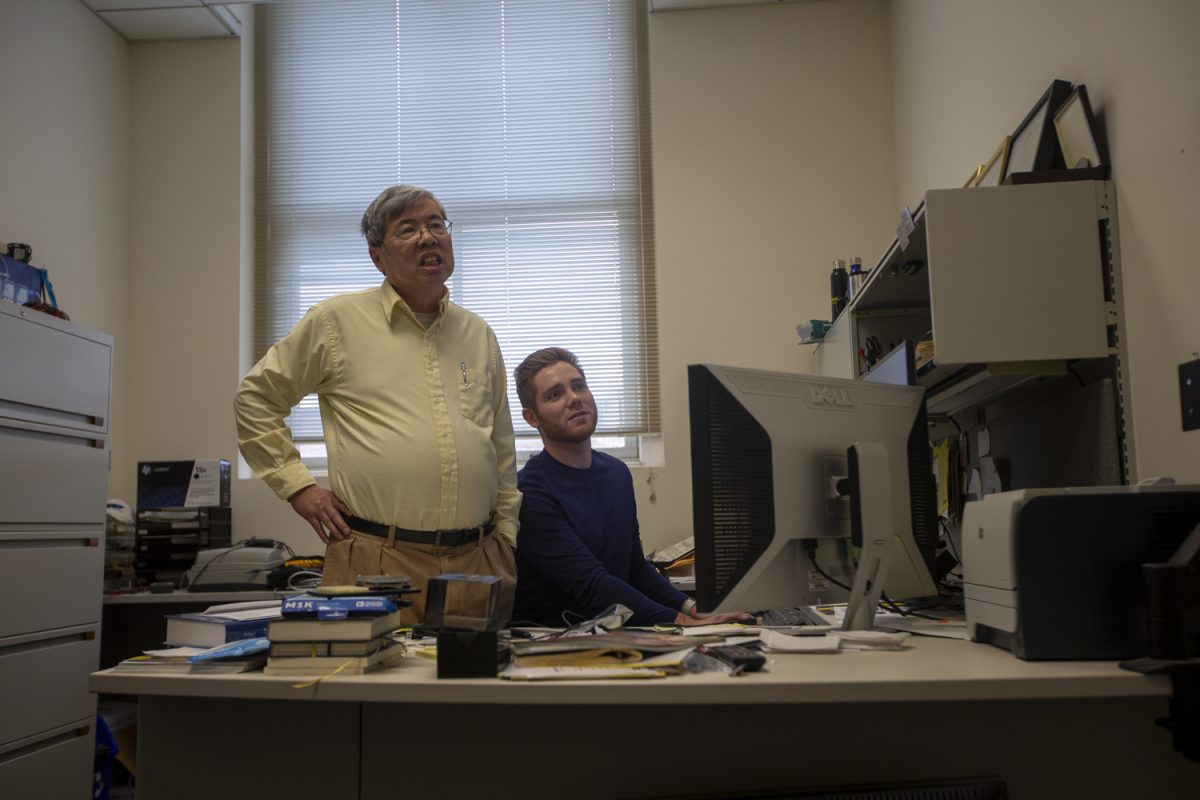

The current shortage has not yet affected the university, said Yusuf Menda, the clinical director of the Positron Emission Tomography Center.

“At this point, we are operating at 100 percent,” he said.

A recent shipment of the isotope from South Africa has helped the department continue to provide all of its tests. But that may not last.

Radioactive isotopes such as technetium-99m are elements used in medical tests to detect various illnesses, including heart disease and cancer.

Technetium-99m decays quickly, preventing harmful radiation from damaging the body. While it is ideal for medical tests, it means the isotope also has a short shelf-life — usually no more than 14 days.

If no new supplies are shipped in two weeks, the department may face potential delays, and some tests — including bone scans for tumors — may have to stop, Menda said.

Doctors may have to stop some exams, which can have a big effect on the quality of patient care.

“People are going to have to get a test that isn’t as good,” said Michael Graham, the UI director of nuclear medicine and president of the Society of Nuclear Medicine. “Or one that’s more expensive.”

The Chalk River plant in Canada, which supplies approximately 50 percent of medical isotopes used in the United States, is one of only six such reactors in the world and the only plant in North America.

Together with a reactor in the Netherlands, the plant supplies two-thirds of the world’s supply of the isotope.

Advances in the past two years have allowed some exams, including those on the heart, to be performed with other isotopes. But technetium-99m remains the main element used in medical tests.

No one is sure yet about the severity of the plant’s leaks, however, Graham said.

“We hope it will be fixed in a few months,” he said. “But if there are more problems, it may be a long time or never.”

And with most of the current plants nearing the end of their expected lifetimes, new sources of the isotope will soon become necessary. Plans for building two plants in the United States are in motion, Graham said.

The cost of building a new plant is around $250 million, arguably too pricey for the United States to establish one of its own.

Still, some say the possibilities of losing thousands of jobs and reducing the quality of patient care is hard to ignore.

“If we can’t do [the tests], technologists will be just standing there, waiting for somebody to come,” Graham said. “That won’t last very long.”