As students’ minds wander, some may find it easier to focus in class if the professor took an extra step — a simple PowerPoint.

“It’s hard to pay attention, and you have to rely solely on yourself to get notes,” said University of Iowa sophomore Mary Westlund. “I record the lectures so I can go back and listen to them … I have to.”

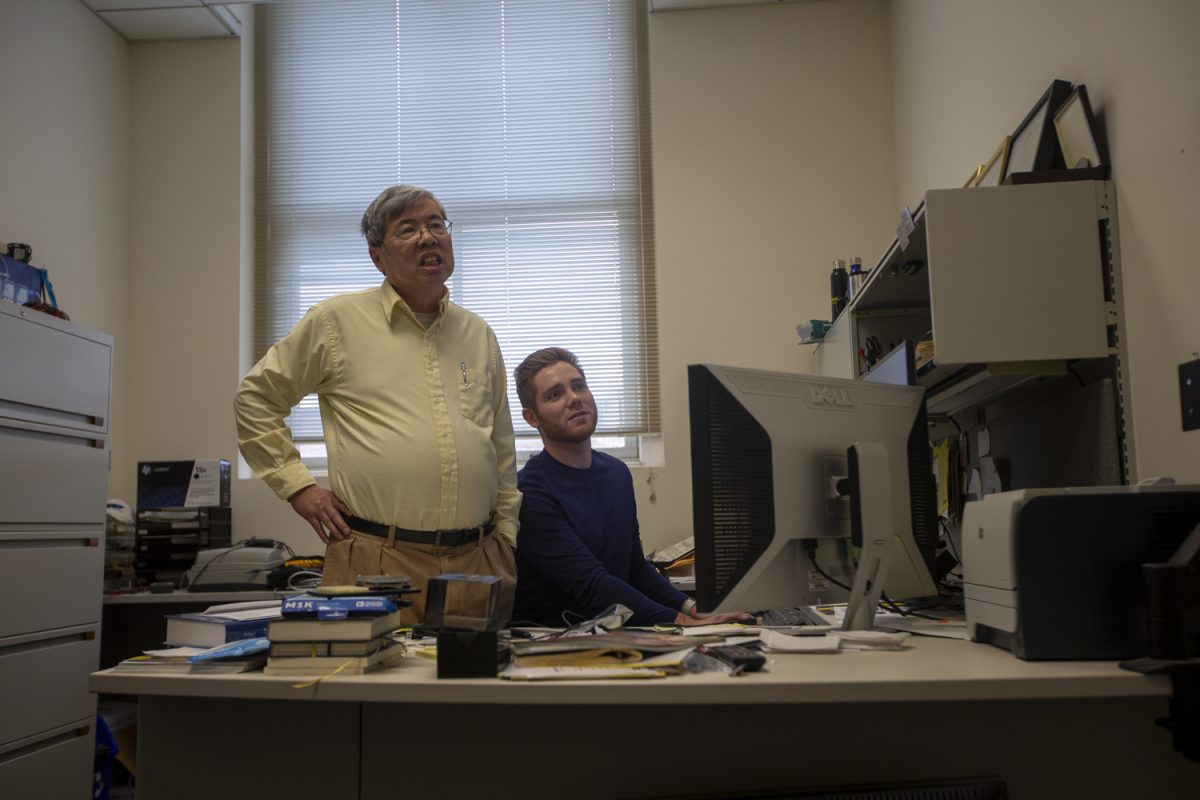

Graduate student James Bigelow led a memory study after studying memory in non-human primates, where he found the primates remembered more of the things they saw and touched as opposed to what they heard. Bigelow and fellow researchers then decided to pursue a related question in humans to see if they showed the same pattern of results.

“Many studies in the past have used words in their studies of humans, but we wanted to know how basic sensory processing might compare,” said Amy Poremba, an associate professor of psychology who assisted with the study. “The end goal is to understand the neural circuits responsible for different types of sensory memory.”

The researchers discovered when more than 100 UI undergraduate students were exposed to sounds, visuals, and objects to touch, they were least likely to remember the sounds they heard.

Participants were first asked to listen to pure tones, such as a beep, through headphones, as well as asked to focus on numerous shades of red squares as a different part of the study. The participants also felt vibrations through the grip of an aluminum bar as part of the experiment.

Each portion ranged from one to 32 seconds, and as the time delays increased, the participant remembered fewer sounds. Only 65 percent of trials were correct during the time delays.

But the participants’ memory for visual scenes and touching of objects were much better.

“[The students] were still getting about 80 percent correct, so there was a big difference,” Bigelow said.

This study provides implications for the students sitting in a lecture.

UI junior Devon Hubner said without visual aspects of a lecture, information might not be as clear.

Poremba said visual aids might increase memory performance when taking notes, while hearing an oral lecture would only provide tactile and visual stimulation.

“We do know from previous studies and our current preliminary data that memory is better for some words but visual and tactile cues still seem more robust,” she said.