UI alum Michael Weinstock remembers ground zero 21 years later

University of Iowa alum Michael Weinstock was a volunteer firefighter in New York on Sept. 11, 2001. He ran from his apartment to Ground Zero when the twin towers collapsed.

One of the two 9/11 Memorial pools is seen in New York City on Saturday, Sept.11, 2021, the 20th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks.

September 11, 2022

Editor’s note: The following article includes content surrounding the falling of the World Trade Center on Sept. 11, 2001, and other graphic descriptions.

The sound of the towers crashing onto the surface of New York City. The smell of fuel and decomposing bodies. The physical vibrations of the Earth as catastrophe took over.

These are the images that stick with Michael Weinstock, who was a first responder on 9/11. Weinstock started working as a volunteer firefighter in his home state of New York when he was 18 and continued to work after attending the University of Iowa. Inspired by Johnathan, his friend from high school who died while responding on 9/11, Weinstock served for over a decade before he arrived at ground zero.

From the panic in Howard Stern’s voice over the radio to the lasting pain of losing a friend, Weinstock told The Daily Iowan his story of that fateful day.

The planes hit

I moved into a new apartment on September 1, 2001. A real tiny, tiny studio that had two great big windows, and those windows overlooked the World Trade Center. When I moved in, I said to the owner, “This is the best view in New York City. I love it.” I think maybe God really wanted me to be there that day, because I just moved into that place.

Everyone in New York City had this little anecdote where they say, “I was supposed to be there that day.” It seemed like everyone had a story about how they were almost there, that they were supposed to be there that day. I was the only person who wasn’t supposed to be there that day. I wasn’t supposed to be in Manhattan. I was supposed to be chilling on my bed. It was the first day of my vacation.

I was listening to “The Howard Stern Show” that morning. I was lying in my bed, just chilling, and I had no intention of leaving the comfort of my bed. It wasn’t until I heard the fear in Howard Stern’s voice that I climbed out of my loft and looked out the window, because his fear told me this is not a normal plane crash, this is something much, much greater. That’s how I ended up — my life changed because there was fear in Howard Stern’s voice that day.

There was never any question. As soon as I saw the huge — the massive amount of dark black smoke pouring out of the tower — I immediately went into action. I couldn’t not.

Standard emergency protocol

Part of our regulations is that firefighters are required to go to the firehouse. In 12 years, I never violated that rule except for that one day.

As I looked out the window, I saw the smoke that was pouring out of the tower. I knew right away that it was a mass casualty incident.

And so, it was because I had that breadth of experience at 12 years that I said OK, I’m violating standard procedures and I’m offering it to the team. So, I grabbed my bag of emergency medical supplies. And I ran outside, and I weighed down the first truck I saw — which happened to be an ambulance — and I said, “My name is Michael. I’m a firefighter and EMT.”

I grabbed a box of rubber gloves, and I brought it up front to these guys. And I said, “We’re going to have lots of casualties on the higher floors.”

We suspect[ed] that the second tower was hit while we were in the Brooklyn– Battery Tunnel.

And so, the plan was to pull out the stretcher and just fill it with all sorts of equipment that fire victims would need. And then just really, like, treat it like a wheelbarrow and drag it up to the 76th floor and started treating victims. Which, by the way, is nothing they teach you in the academy.

We’re just taking all of our career experience and amending it on the fly to this mass casualty incident.

The first tower falls

We were pulled over by an officer at the scene, and he directed us where to park the ambulance. He said, “I want you to be careful. This is still an active scene.”

[The officer] was choosing his words carefully. What he was saying was, “You’re going to see, as soon as you turn the corner here, there are dead bodies. You’re going to be driving, and try to drive over as few [bodies] as possible, because there were bodies and bodies all over the roadway.

There was a torso here and an arm here and whatever sweater there and that was all over. And I remember I had made eye contact with the guy I was working with, and I’m like, “You good? You good?” [He took] a second to compose himself. And then we were doing exactly what we said we were going to do.

We were loading up the stretcher with medical equipment and oxygen bottles, saline solution — all that stuff. All of a sudden, I felt it before I saw it. I felt the roadway rumble, and I heard dizzy, roaring, rumbling to my left.

We just dropped everything on the ground, and we ran as fast as we possibly could to the closest building to our truck, popping over orange cones and also — quite frankly — hopping over bodies and body parts along the way.

We made it just in the nick of time. Then, the entire building came down right behind us and the ambulance was crushed and destroyed.

[It was like] there was white snow coming down … For the first couple of minutes, I thought it was snowing, I was having a dream. [I thought], thank God, that was really scary. I’m glad that I’m really waking up and my bed is warm.

So, it’s September. And I was 100 percent certain that that was [I] dreaming. And then I would wake up in my bed. I remember thinking, “Oh, thank god, that was so scary. I’m so glad that this is a dream, and I’m going to be waking up in a minute or two.”

And I said to myself, “I’ll keep playing along in this dream.” I’ll keep treating people, but I know it’s a dream. And I’m going to wake up is like a guarantee, and then it just went on for like months, and it went crazy for a while.

And yet, I still — like — there’s this little tiny, tiny part of me that is hoping and expecting that I’m going to wake up from this dream.

The second tower falls

The first time [a tower fell down], we all rushed into that building and found some safety and we’re treating injured people … [and then] a police officer had everyone gathered up near the elevator, and he raised his hand and he said, “OK, I want everyone to form a single file line.”

There’s a staging area being set up at Battery Park, and we’re going to work in a walk up. And I tapped him on the shoulder and said, “Listen, I don’t know what the hell’s going on out there. But there are dead people all over the ground. But this is a nice, safe old building that would lock the marble, and we should sit tight by these elevator banks for at least 25 minutes to an hour. Then once we’re certain that it’s safe outside to move people, then we could move.”

He didn’t even look up to see who I was. He didn’t know if I was a younger guy. He just nods his head, [and] he says, “Ladies and gentlemen, change your plans. This is a nice, safe old building, and we’re safe here.”

And about five minutes after, that is when the second tower came down. If these civilians had been outside as the officer wanted, they all would have been crushed. It’s because I had had a drill at my firehouse after there was a traditional fire in an apartment building, and the former chief gave the drill and made a point of telling all of us what to do during a mass casualty incident and during a serious emergency.

If you’re going to move civilians, you need to stop and ask yourself, “Am I 100 percent certain that I’m moving the civilians from an area of danger to an area of safety?” If you can’t say that with certainty, then you don’t move the civilians.

Johnathan Ielpi

The best part [of the anniversary] is that I get to talk about my friend Johnathan. I think about him every day all year long. But on this day, people have to listen.

He was a great mischievous human that I loved. He was my best friend.

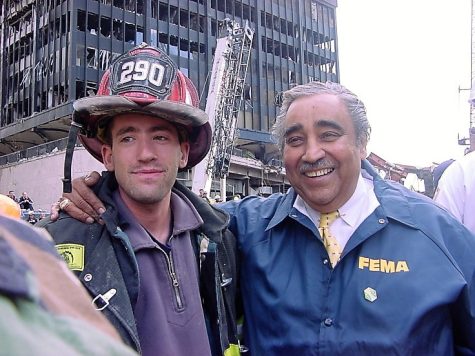

When I ran for office [in 2020], the president of my old fire company sent out a press release to local papers saying that I was never a firefighter at ground zero. That was ludicrous. And the accusation didn’t really stick because the photos spoke volumes.

I think he was motivated by envy. He didn’t like the fact that I was receiving favorable attention from my service down there. Envy makes people do dark things.

When the president of our fire company sent out that press release, he also sent my campaign a cease-and-desist letter and, via stationery, and he forbade the campaign from producing campaign literature that included me wearing my fire gear at ground zero. When I got a cease-and-desist letter — which is completely illegal by the way, it wasn’t justified — I imagined Johnathan standing behind me as I was reading the letter, and I imagined him just laughing and laughing and laughing. I felt so much better.

I had been so upset, and it was just so ludicrous. The accusation was just so stupid. Having the image of Johnathan laughing, which I knew he would, made me feel better, like, instantly.

The aftermath

The president came down. I think it was the 15th of September. That day was really tough, because rescuers wouldn’t admit it, but we learned in training that this is the day that you learn that people are either recovered — they’re pulled out of the rubble by this day — or they’re not.

It was really nice that President Bush came that day. And nobody was [a] Democrat or Republican that day. Now, remember, we were told by the Secret Service that the president wants to come and shake hands and thank you guys. And everybody in my truck was dismissive.

The president came through and I could see exactly what he was doing. He was going to choose one specific firefighter to come up on board to stand next to him. Because I worked in politics and I knew a little bit about how things go, I thought about stuff I could say to the president to get chosen.

I thought of the advice that my college roommate’s father told me freshman year at Thanksgiving dinner in Iowa. He said to me one day, “Michael, your life should never change formatively in one day, for good or for bad. It’s not good, and it never ends well. I hope that never happens to you.”

The president came through and I didn’t tell him what he wanted to hear. He said, “Son, I’m very proud of you. Your country’s very proud of you. I want you to keep up your work here and stay strong,” And I said, “Thank you Mr. President.” I am so glad that I didn’t look for the attention.

[After 9/11], I was a mess. I was. I wasn’t sleeping. I lost like 15 pounds. I was traumatized and I wasn’t myself. I dove into weightlifting. I made sure I was at the gym five or six days a week. I went heavy into snowboarding that season, because I found that when I was going down the mountain it was the only time I wasn’t thinking about 9/11. I was just thinking about the five feet in front of me. It did catch up with me about 10 years later with PTSD and depression.

I went to the synagogue in the morning. I woke up and I’d go to the synagogue at 7 a.m. The rabbi had everyone praying for my friend Johnathan.

In the days that followed, the immigrants had pushcarts and were giving away bottles of Snapple. All the signs up and all the windows that said, “bathrooms inside.”

I found myself at the base of the Manhattan Bridge surrounded by tourists. They were tourists and had cameras around their neck, and suddenly, New York City was a warzone. I heard different people introducing themselves to strangers and asking them if they wanted to stay at their homes. All of the guys in little boats who came over were waved down to bring civilians over across the river to New Jersey where it was safe. New Yorkers really stepped up to the plate.

That made me very, very proud.

This interview was edited for clarity. Kate Perez contributed to this report.