A recent University of Iowa study reveals a vaccination used to treat dogs with leishmaniasis could be effective in containing its spread to humans. This can especially benefit Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans.

Leishmaniasis is a tropical infectious disease found in 98 countries around the globe. According to an estimate from the World Health Organization, it kills approximately 20,000 to 40,000 people a year in mostly five countries: Bangladesh, Brazil, Ethiopia, India, and Sudan. It also kills thousands of dogs.

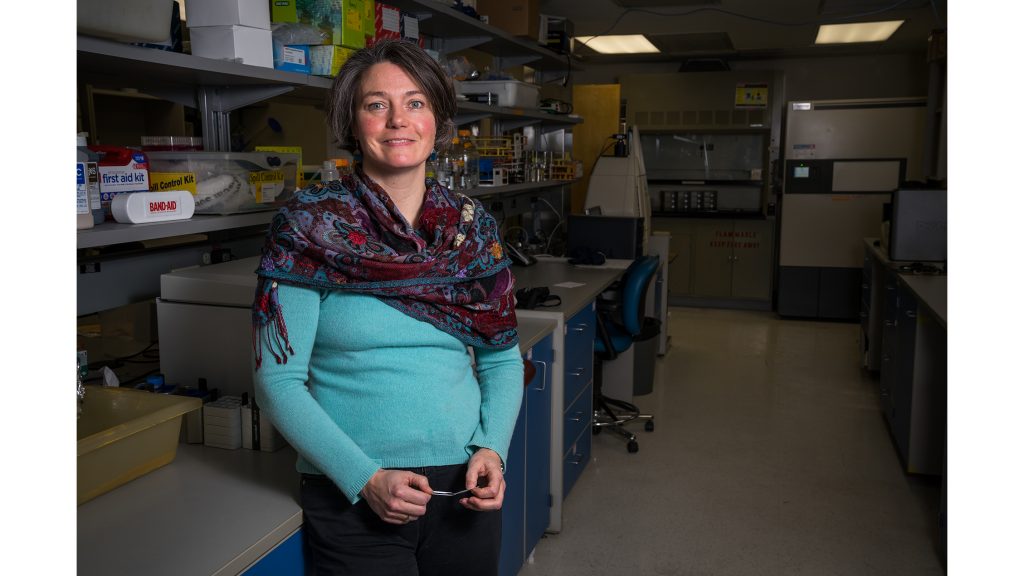

Aside from people, the group of animals that are mainly infected with this disease is dogs in almost half of these countries, said Christine Petersen, the author of the study and a UI associate professor of epidemiology. This group of animals is called the reservoir.

“There are three vaccines that can be used to prevent this disease in dogs,” Petersen said. “However, [there are] no vaccines for people.”

The disease is transmitted from the reservoir to people mainly by sand flies, said Marin Schweizer, a UI assistant professor of internal medicine.

“It is mainly [prevalent] in countries that have sand flies,” she said.

The vaccine is similar to that for rabies, she said. It can be used after exposure.

“Usually when you get a vaccine, you are preventing the infection,” Petersen said. “But here, we were vaccinating dogs that were already exposed to the parasite, and we wanted to see if the vaccine could stop it from becoming a sickness.”

In this case, vaccines were given to dogs that had already been exposed to the parasite, she said.

The study could be beneficial to Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans — around 5 to 20 percent of those war veterans are infected with leishmaniasis. According to an Iowa Now press release, the vaccine could be a step toward clinical trials for humans.

“Soldiers that travel to these countries and walk around sandflies mainly get infected,” Schweizer said.

If people travel anywhere and contract leishmaniasis, they can fight it, she said. But if something else happens, leishmaniasis can come out.

“Most soldiers are fairly healthy,” Petersen said. “What I worry about is that as these soldiers get older and their ability to fight infection gets worse or they drink too much, [it] is when leishmaniasis is going to come out.”

In places such as Sudan, India, Bangladesh, Ethiopia, and Brazil, problems can start immediately. However, in the United States, it is something that develops chronically.

New methods and algorithms were developed for the study to conduct statistical research, said Grant Brown, a UI assistant professor of biostatistics.

“It is particularly difficult to study this disease,” he said.

There are some difficulties when it comes to conducting data surveillance and finding where it occurs, Brown said. Modeling and prescribing are also challenges.

It is an important first step in public-health interventions, Brown said. A few graduate research assistants also worked with on developing algorithms.

“No previous study has looked at using a vaccine as immunotherapy to improve the immune response in an animal that is already naturally infected,” Petersen said. “So, to show it was safe is a big deal.”