Icelandic film Rams crosses genre lines to bring the story of rival brothers to the screen.

There is seemingly nothing that can repair the decadeslong rift between Icelandic brothers and rival farmers Gummi and Kiddi.

Their interactions occur only when they absolutely must, and one of the only such occasions is their village’s annual “best sheep in show” contest, in which the brothers are famous foes. To further heighten their competition and place an absurd emphasis on their mutual estrangement, their farms lie adjacent to one another, not much more than a few fences separating their flocks.

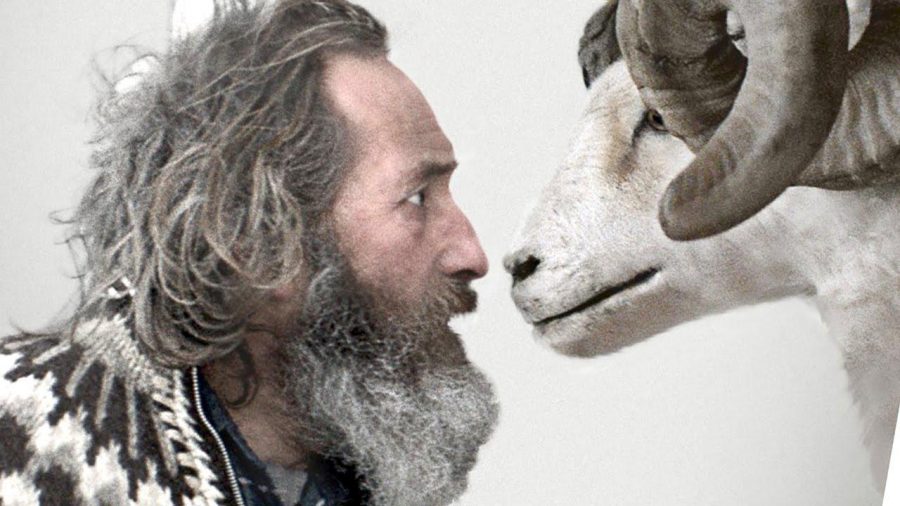

We meet the brothers and protagonists of Rams — two older, cantankerous fellows whose humanity still manages to pierce through their overflowing facial foliage and wind-weathered visages — at a time when disaster threatens both their livelihood and, ironically, their feud. That threat emerges in the form of the highly contagious and largely fatal virus scrapie. (Think mad-cow disease, but for sheep.)

The film follows the two men as they aim to reconcile nearly 40 years of animosity to preserve their agrarian way of life in an age in which even nature is seemingly prodding them to conform to modernity.

From an outsider’s perspective, the notion that it takes the threat of losing a few flocks of sheep to mend a relationship between family members seems frivolous at best. But there is a deep-rooted and honest sadness in all of this apparent absurdity, one that the director Grímur Hákonarson expertly extracts and puts on display. The film toes the line between relatable and foreign, functioning both as a black comedy about sibling rivalry and a deeply unsettling tragedy about the possible extinction of an entire lifestyle.

Throughout the course of the film, we become strangely attached to this lifestyle, and the characters — despite their shortcomings and eccentricities — grow deeply relatable to us. In them, we see aspects of ourselves which have progressively drifted farther and farther away from us. Despite all of its advantages and repeated claims that it brings us all closer together, there is an eerily unignorable sense of disconnect that the modern world has cast over all of us. In Gummi and Kiddi’s struggle to save their farm, we are transported back to a time when the immediacy of a problem could not be distilled through social media or any of the other coping conventions of the modern world, and instead had to be confronted head-on.

In addition to stellar performances by the film’s two main actors, Sigurður Sigurjónsson and Theodór Júlíusson, much of the credit for the rendering of this intense identification is owed to the camera work of Sturla Brandth Grøvlen. Grøvlen’s cinematography depicts a strikingly fertile landscape, which, when framed by the paradoxically bleak skyscape, creates a portrait of small-town life, unafraid of showcasing both its starkly limited and strikingly expansive nature.

The film is a resounding success that is at times a comedy, a drama, and a documentary-like social commentary; in this combination it nearly achieves cinematic perfection.