Pride amid a pandemic: Iowa City celebrates 50 years of LGBTQ visibility online

50 years ago, the first group of LGBTQ University of Iowa students marched in the Homecoming parade as members of the Gay Liberation Front. The DI took a look back over 50 years of LGBTQ visibility in Iowa City.

June 16, 2020

With the COVID-19 pandemic continuing to wreak havoc around the globe in mid-April, Iowa City opted for an online Pride parade to celebrate 50 years of LGBTQ visibility in Iowa City. Drag queens, drag kings, and LGBTQ community members will be streaming their drive through area neighborhoods on June 20 for the “Our Pride We Will Maintain” series.

In addition, Iowa City Pride will be hosting other virtual events, including a “Queer BIPOC Transgender Discussion” and a broadcast of global pride events on Facebook and YouTube.

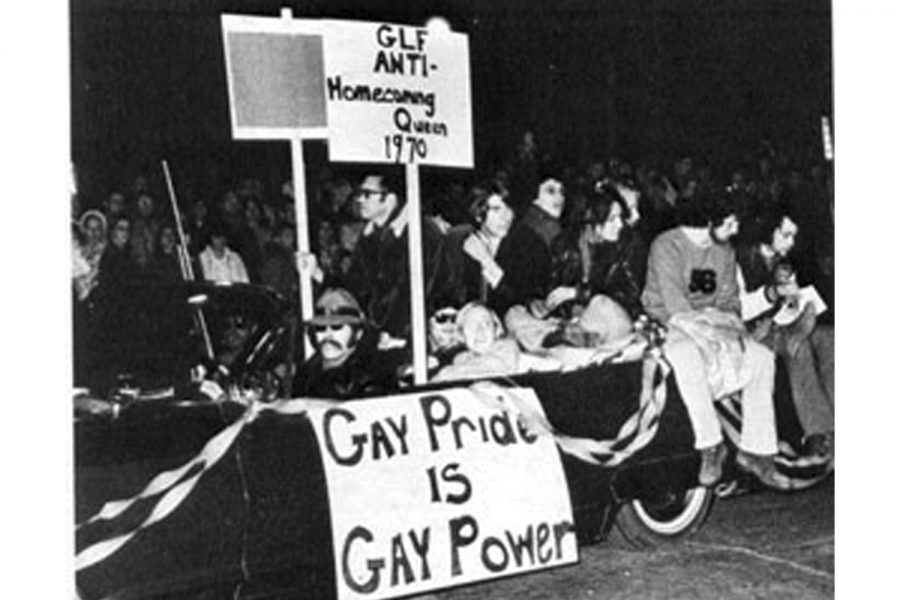

Although Pride won’t be held in the format that Iowa City residents are accustomed to, this won’t be the first time Pride looked just a little bit different. In 1970, members of the Gay Liberation Front, which would later become Spectrum UI, participated in the University of Iowa Homecoming parade with a sign that read “Gay Pride is Gay Power.”

That year, the UI had approved the Gay Liberation Front as a student organization, making it the first LGBTQ student org recognized by a university in the United States. The Daily Iowan covered the parade, writing the headline, “Homecoming Parade Was Just a Little Bit Different.”

According to the DI’s coverage, toward the end of the parade, a girl joined the group as they passed by her. When asked why, a member of the group replied, “You don’t have to be gay to help, like you don’t have to be a soldier to help fight to end war.”

Following the Oct. 16 Homecoming display, the DI ran a series of articles covering the Gay Liberation Front’s agenda, which included efforts to decriminalize sodomy and address the unequal treatment of gay people by police.

The group changed its name to the Gay People’s Union in 1975. While there was still focus on political issues, members also provided services and resources to LGBTQ students that weren’t made available by the university, such as LGBTQ educational programming.

The Gay Affiliates of Iowa was founded in Iowa City 1978. The cohort was Iowa’s first statewide organization to advocate for gay rights. According to the University Archives at the UI library, its first meeting was held at the Iowa Memorial Union.

University archivist David McCartney said the importance of college towns’ contributions to LGBTQ rights can’t be overstated. McCartney has researched LGBTQ history at the university since he and his partner moved to Iowa City in 2001.

“I think college towns in general are the cradles of gay liberation that we don’t think of in historical terms as much as we do San Francisco or New York or other large urban centers,” McCartney said. “Those college towns that might seem like outposts are very much out front as well.”

Since then, LGBTQ advocates in Iowa City have educated people about safe sex during the AIDS crisis and participated in The Names Project — a project started in 1987 that honored those who died from AIDS.

To honor those lost to the disease, the group displayed sections of a quilt that would later be sent to Washington, DC to join quilts from all around the country. Each section of the quilt represented individuals who died of AIDs, according to the project’s website.

The Names Project wasn’t the only artistic endeavor at the university that honored major events in LGBTQ history. In January of 2020, Hit the Wall, a theatrical retelling of the Stonewall riots was performed at the university’s theater building.

Stonewall is widely regarded as “the first Pride” in the LGBTQ community. The Stonewall Inn in New York City was a gay bar that became the target of police raids in 1969.

RELATED: Hit The Wall brings story of Stonewall riots to UI stage

On the night of June 28, LGBTQ people fought back against police, resulting in riots that lasted until July 3. According to a previous interview with UI professor and theater historian Kim Marra, it sparked the movement for LGBTQ rights.

“On this particular night, they said, ‘We’ve had enough, we’re not going to go through this anymore. We’re not going to hide. We’re not going to let this happen to us all the time,’ and they burst forth in flagrant opposition,” Marra said.

Hit the Wall aimed for historical accuracy on all levels of production, according to Director Bo Frazier and dramaturg Luke White. The duo took a trip to New York City in June of 2019 to research Stonewall firsthand.

There, they met the people who were present at the Stonewall uprising, and saw various events, exhibits and performances that were, said White, ‘in conversation’ with the uprising.

“I mean, it’s not every play we get to do that ‘in the field’ research,” White said. “But it just was like an experience that I as a queer man will never forget.”

Having only first heard about the Stonewall uprising through former President Obama’s second inaugural address, White added that the Stonewall uprising, like a majority of LGBTQ history, is not taught to students.

White learned while researching the events that took place at Stonewall that he knew only the bare bones of what happened: a riot broke out in a bar in NYC in 1969, and the LBTQ movement was born.

“That’s all I knew. And I’m gay, right? So if that’s my experience, just think about the 30,000 students on our campus,” he said. “Especially if you’re not of the community yourself. It’s just still so unlikely that you would encounter this history, partially because it’s still fairly recent history — we tend not to learn the most recent history — and partially because of ongoing discrimination against the LGBTQ community.”

During every rehearsal and performance, Britny Horton — who played the character of Roberta in Hit the Wall — said that the cast had the responsibility to recount history. The actress added that artists bring people together and help heal and educate others.

“Imagine how many people weren’t educated about Stonewall,” she said. “Even I came to that experience not having two clues about it, right? But I left there much more informed and much more prepared to navigate my social circles, and to speak out against inequalities in all communities.”

The opening night of the performance was followed by a celebration where UI President Bruce Harreld vowed continued support of the campus LGBTQ community.

Harreld’s speech mirrored some of the language currently being used by the university to express support for the Black Lives Matter movement. In a message to the UI community on May 31, Harreld wrote that the university will not tolerate anything but a safe and inclusive campus for people of all backgrounds and that civil discourse is a cornerstone of higher education.

Akia Nyrie Smith, a Black Lives Matter activist and drag persona, said, “The queer community, in my opinion, has always been supportive of Black Lives Matter and marginalized communities.”

Smith performed in Hit The Wall. During their research for the show, Smith learned the Black Panthers supported the Stonewall uprising. Smith said the two groups shared common ground.

“It’s about difference and uniqueness, and finding pride in that uniqueness that might not be ‘normal’… It’s beautiful and validating, and you should let everyone know you exist because it’s needed, and that’s exactly the Black Lives Matter movement in a nutshell.”

Although 2020 Pride won’t be an in-person parade, its celebration in any form still provides a sense of community.

“It’s about the validation and affirmation that our existences are not only okay but they’re also beautiful,” Smith said. “And it obviously goes deeper than that, it’s making sure we’re represented in our education and our institutions and our society so if and when that happens people will be able to walk around proud and not afraid.”