Midwestern creators push for a more nuanced definition of Midwestern art and detail

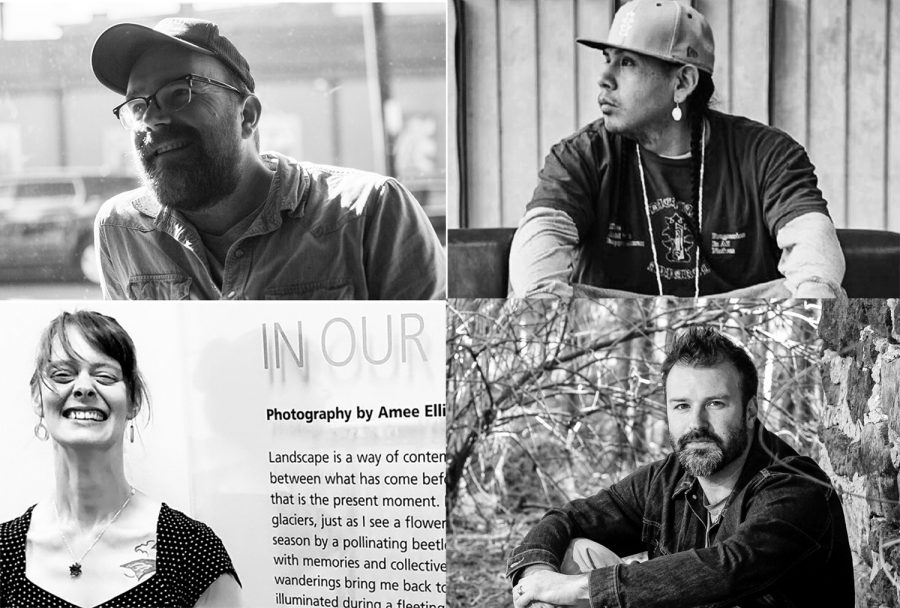

Four Midwestern artists share how Midwestern landscape, culture, and history have inspired their art and why the Midwest is the perfect stomping ground for up-and-coming creators.

March 5, 2020

The Midwest: red barns, fields of corn, and gravel roads winding through small, rural towns. Renowned artists like painter Grant Wood and songwriter John Prine have found inspiration in the rolling farmland and down-to-earth attitude of this area, rich in agriculture and heart. From Wood’s depiction of green rolling fields in Young Corn to Prine’s folksy lyrics about the subtle profundity of mundane life in songs such as “Hello in There,” Midwestern art provides a vision of life that is quiet and humble.

But that vision is only a small piece of the Midwest, and modern Midwestern artists have a broader, more diverse perspective on creativity in the heartland and what the Midwest has to offer the national art scene.

Joni Kinsey, a University of Iowa art history professor at the University of Iowa, suggested that the definition of Midwestern art can include all of its stereotypes and much more.

“All of the stereotypes are part of Midwestern art, and ought to be, because if it didn’t include those things [nostalgia, farms, blue collar work] it wouldn’t be distinctive to this particular region,” Kinsey said. “At the same time, there’s a huge array of diversity. Here on [the UI] campus, we have artists that work in all kinds of media and styles and have international careers, and how are we to say they’re not Midwestern?”

Kinsey noted that while Midwestern art doesn’t fall under any singular generalization, most art inspired by the landscape, culture, or perspectives of the Midwest has at least one trait that identifies it as Midwestern in nature.

Amee Ellis, a Des Moines-based photographer, echoed Kinsey’s sentiment, and she said while undeniably tied to Midwestern landscape, art that’s inspired by the Midwest isn’t always so obvious.

“Do I think that all Midwestern artists need to portray the ‘Midwest’ in their art? No,” Ellis said. “But certainly our Midwestern sensibilities, our wry sense of humor, is always in there somewhere.”

Ellis grew up in the Chicago area and spent many years of her adulthood in California before relocating to Iowa City with her husband. Ellis said her Midwestern homecoming led to her seeing the Midwest in a different, more positive light, and that it became the center of her art.

“My work is really about that place where my personal memories of growing up in the Midwest meet with this long and natural history of the Midwest, and our collective history as Midwesterners,” Ellis said.

The mix of personal and collective attachment to a Midwestern identity was an important facet of Nickolas Butler’s art as well. Butler, an alumni of the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop and author of the bestselling novel Shotgun Lovesongs explained that much of his writing is inspired by generations-old familial relationships and how those families are married to their Midwestern lands and communities.

Butler also said that Midwestern identity in art is often complex and doesn’t mirror the stereotypes it often becomes associated with. Complicating the definition of Midwestern art is important, he said, not only to change national perspectives of the Midwest but also to allow Midwestern artists more creative freedom.

“It’s convenient to think that Midwestern art only looks like Grant Wood paintings or Garrison Keillor essays from the 80s, but I don’t want somebody to read my books and think that’s all that I could be,” Butler said. “I would rather be affiliated with a much more complex mosaic of art than just being nostalgic about farming and blue collar factory work.”

The mosaic of art Butler references is one that includes an extraordinary variety of mediums, historical and modern influences, and themes. According to Dawson Davenport, a member of Iowa’s Meskwaki tribe, the mosaic cannot be complete without the inclusion of Native American art.

“You can’t tell the story of the Midwest without the indigenous people,” Davenport said, and went on to explain that artists like Grant Wood and Garrison Keillor have only depicted a very recent version of the Midwest. “What I do, and what many indigenous Native artists do, is pull from thousands of years ago, from knowledge passed down to us.”

Davenport, an alumni of the University of Iowa, is a versatile artist who is, according to Davenport, often described by his peers as a “Native futurist.” Growing up, he fed his artistic passion by experimenting with hip-hop, cartoons, and graffiti. These childhood influences are still present in Davenport’s current artwork, which mixes old generational wisdom with modern phenomenons like social media. Davenport creates in a multitude of mediums, including sculpting, screen printing, and writing.

Versatility is also a noticeable quality of Iowa City musician Brian Johannesen’s work. Johannesen’s music is an impressive mix of genres. His latest album, “Holster Your Silver,” which debuted Jan. 31, featured blues, Americana, rock, and country. Johannesen said that, contrary to popular belief, expansiveness and change are key traits in Midwestern art.

“If you listen to almost any Midwestern record, it has this pastoral sound to it, as if all the seasons have been baked into the music,” Johannesen said. “I think it’s a harder thing for people who are not from the Midwest to comprehend. They think of it as being flat and boring, when in reality it’s beautiful and it changes so much depending on where you are.”

Ellis took that idea further, joking that while her friends often make fun of her for enjoying level, empty landscapes like those of Nebraska, she has a real justification for her love of flat spaces.

“Places that are flat are stunning when you think about what made them flat,” Ellis said, referring to the glaciers that moved across the Midwest during the Ice Age. “It’s incredible to think about the natural history and the incredible forces and energy that created these prairies.”

While agricultural landscapes and collective or personal regional identities are certainly traits that are important to both historical and modern Midwestern art, Butler added that it’s not just the subject matter that identifies art as Midwestern, but also the artist’s medium.

Butler, who lives in his hometown of Eau Claire, Wisconsin, cited Nick Wroblewski, a woodcutter from Duluth, Michigan, and Josh Swan, a boat builder based in Ashland, Wisconsin, as creative role models.

“I’m inspired by the way he lives his life close to the landscape,” Butler said of Swan. “He’s making art, but he’s making art that’s fueled by the landscape.”

Ellis’s photography is also fueled by the landscape. She described Iowan land as undramatic, which is a quality she appreciates when creating her art.

“The thing that attracts me to the Midwest landscape is its subtlety,” said Ellis, who shoots all of her photos on black and white film. “It’s not that grand Ansel Adams beauty; it’s rolling hills, woods, and streams.”

While other artists might disagree with Ellis and flock to areas with grandiose mountains and bustling cosmopolitan cities, Butler, Ellis, and Johannesen all agreed that the Midwest provides artistic opportunities that other regions can’t.

“The great thing about the Midwest is that it provides artists with freedom to do whatever you want,” Johannesen said. “Even in Chicago, which has a big music industry, you can tell the music coming from there is still free of expectations in ways that music from New York or [Los Angeles] will never be.”

Butler echoed Johannesen’s sentiments and said that, despite the fact that many successful artists leave their Midwestern homes in lieu of a more glamorous coastal life, the Midwest is actually a wonderful place for artists to put down roots.

While the Midwest provides an affordable place for working artists, creators still have to grapple with the possibility of their art getting less attention than art from other areas. According to Davenport, this issue is particularly prevalent for Native American artists.

“As far as Native art goes, a lot of the stuff that gets attention and is spoken about is art from the southwest,” Davenport said.

Although Davenport said he’s felt pressure to move to other regions where there are more opportunities for indigenous artists, he stated that he has found his place as an artist in Iowa City and nearby communities. Davenport has his own fashion brand called Daepian and is currently working on creating a gallery that features Native American art. He intends to use the gallery, as well as his own art, to help educate the Iowa City community about the Meskwaki people and other woodland tribes in Iowa.

Butler encouraged artists like Davenport, who use their art to teach and support their communities, to place less importance on national perspectives of Midwestern art and more on local consumers who will feel a more intense connection to the art.

“People want to hear a genuine voice talk about their specific place on the planet,” Butler said. “When I was in my early 20s and trying to figure out if I wanted to be a writer, I was reading the work of a guy named Jim Harrison, who’s from Northern Michigan. Just seeing him write the names of Midwestern small towns that I had been to did something to almost validate my existence. I thought ‘I’ve been to those places, therefore I must exist. I’m here somehow.’”

Kinsey expressed a similar sentiment. Inspired by Grant Wood’s open appreciation and love for the Midwest, Kinsey had some advice for burgeoning Midwestern artists.

“Midwesterners need to claim, with pride, their region and their affiliations with this place, even though it doesn’t have some of the things that people elsewhere think are exciting or valuable,” Kinsey said. “We need to appreciate where we are and celebrate that, whatever that might mean.”