UI plasma-wave instrument teaches researchers about heliosphere

University of Iowa scientists are leading the way in managing the plasma-wave instrument connected to the Voyager 2 spacecraft, which is teaching researchers more about the heliosphere.

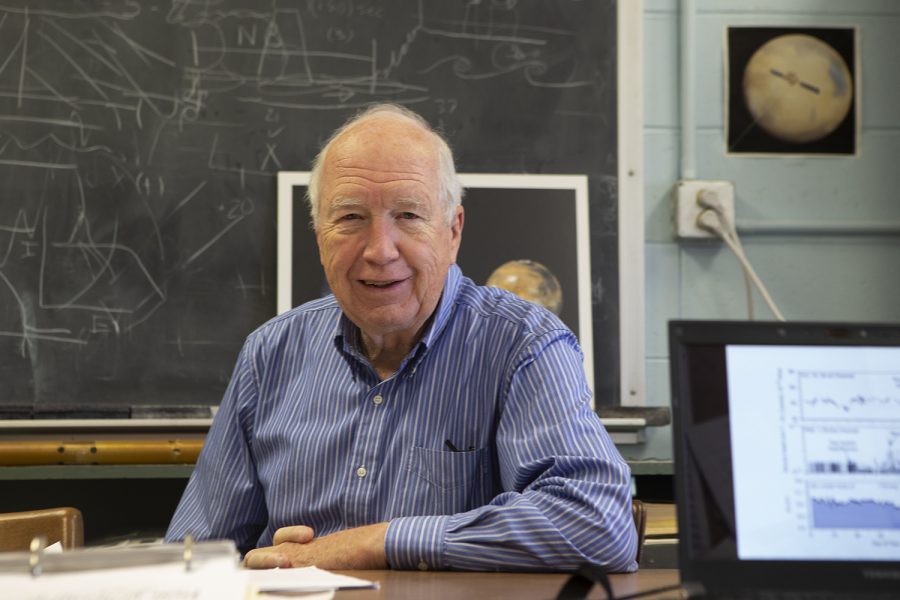

University of Iowa Scientist, Don Gurnett, is photographed in his office in Van Allen Hall on Tuesday, November 12, 2019. Gurnett took part in creating the vital instrument for Voyager 2. (Raquele Decker/The Daily Iowan)

November 12, 2019

As the spacecraft Voyager 2 became the second human-made object to leave the solar system in 2018, two University of Iowa scientists led the way in managing an instrument to produce data that is reshaping how people understand the solar system.

The plasma wave instrument — which was constructed and managed by UI scientists — has produced discoveries that appear to affirm knowledge about the nature of the heliosphere’s boundary uncovered by Voyager 1, which left the solar system in 2012.

“You can consider the heliosphere as the region dominated by the sun’s atmosphere. The sun is the source of gas that blows past all the planets at supersonic speeds and continues to go out until it starts to run into the interstellar medium. The heliopause is that boundary between interstellar medium and the interplanetary medium,” UI research scientist Bill Kurth said.

Kurth is a co-investigator on the project with principal investigator and professor emeritus Donald Gurnett. With a 60-year history at the UI, Gurnett said he has seen the evolution of what astronomers believe the heliopause actually was and the influence of solar winds.

“There were two ideas about what would happen to solar wind. One was that the solar wind would gradually get absorbed. The other is that the solar wind would develop a boundary which separates the solar wind from the interstellar medium,” Gurnett said. “It’s an incredible fact that fluids [gases and liquids] like to form boundaries.”

Gurnett said that, in the beginning, there was virtually no evidence of gas actually present between stars beyond the solar system, and some astronomers even thought the heliosphere only extended until about the distance of Jupiter.

“I’m actually one of the [people] who really promoted [the idea of a sharp interstellar boundary], that there should be a big density jump going from the solar wind going into the interstellar medium,” Gurnett said.

RELATED: NASA head talks space exploration at University of Iowa visit

The instrument the UI team developed is specialized to detect the measurements needed to examine this boundary. Gurnett said detection by their instruments on Voyager 1 convinced NASA that the spacecraft had exited the solar system.

Voyager 2 detections, while not identical, appeared to support the prediction about density changes at the heliopause, Gurnett said.

UI Systems Architect Larry Granroth, who like Gurnett and Kurth spent decades in connection to the Voyager spacecrafts, said that these missions have provided a wealth of knowledge about the solar system.

“During the planetary flybys, textbooks were literally being rewritten to incorporate the wealth of knowledge these high-resolution (and in the cases of Uranus and Neptune, first) observations were revealing,” Granroth said in an email to The Daily Iowan.

RELATED: University of Iowa receives grant from NASA to study auroras

Gurnett and Kurth, despite lifetimes’ worth of experience, are still awed by the contributions Voyager 1 and 2 produced for humanity’s grasp of the universe.

“From my perspective, the Voyager missions including both spacecraft is — and people would argue with this statement — the greatest space mission that’s ever been flown. These are the only two spacecraft that have lasted long enough to make measurements in the interstellar medium,” Kurth said. “It opened our eyes to the outer planets. They really set the stage for the exploration of the outer solar system.”