Two UI professors bring their experimental films to a world-wide audience at two international film festivals

University of Iowa cinema professors Michael Gibisser and Christopher Harris share the process of making films that were worthy of two of the most high-profile film festivals in the world.

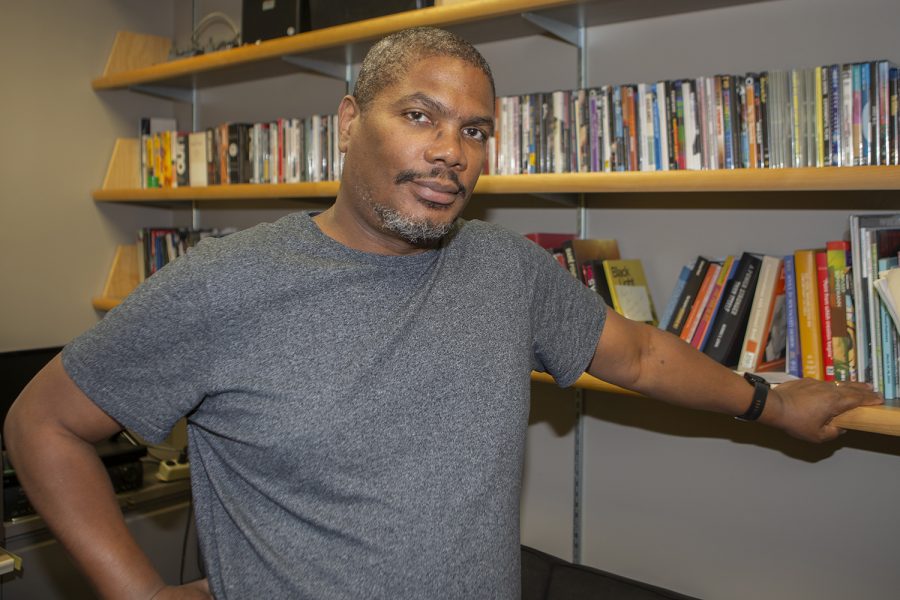

Associate Professor Christopher Harris poses for a photo in his office in the Alder Journalism Building on Tuesday, October 22nd, 2019. Harris is the head of film & video production of the University of Iowa department of cinematic arts and his documentary *still/here* was shown at the 2019 Locarno film festival in Switzerland.

October 22, 2019

In the world of experimental filmmaking, a filmmaker can never be sure how their work will be received, so being invited to one of the most high-profile film festivals in the world is an indicator of monumental success.

Two University of Iowa professors, Michael Gibisser and Christopher Harris, received this honor.

Gibisser, assistant professor in the department of Cinematic Arts, was invited to debut his short film Slow Volumes on Sept. 6 at the Toronto International Film Festival. The event is one of the most heavily attended film festivals in the world.

Gibisser began conceptualizing the project a few years before its release. He knew he wanted to use an unusual type of camera to create a specific visual experience.

“If it was showing an image of this room, it wouldn’t show you the entire room, it would show you a very thin sliver of the room, kind of flowing in time,” Gibisser said. “In doing that, it creates these kind of very strange, abstract colors and images.”

To do this, Gibisser used 35 millimeter film, a camera he built himself, and some trial and error.

“It took a while to figure out how to use it correctly, because the common ways we think about measuring light for film cameras didn’t apply, so I had to do some trial and error to figure out how this was going to work and how to make a project out of it,” he said.

Creating a narrative wasn’t Gibisser’s goal. He said he wanted to use visuals to challenge the audience’s perception of what reality looks like.

“It’s called [an] experimental film in some part because I didn’t know where I was going to end when I started,” Gibisser said. “I don’t know that there’s a singular thing the film is meant to say. It’s just meant to pose questions.”

Harris was invited to Locarno Film Festival in Switzerland to showcase his film still/here. Locarno is considered to be one of the “Big Five” international film festivals, according to Harris, as well as one of the oldest. By being invited to showcase his film there, Harris joined the ranks of filmmakers such as Spike Lee, Oscar Micheaux, and Charles Burnett.

Harris’ film originally premiered nearly 20 years ago, in 2000, but has recently become more well-known due to media coverage and other film festival showings.

“The world is just now catching up with my brilliance,” Harris said with a chuckle. “I’m only half joking.”

Harris’ film is an experimental documentary that shows life in African-American communities in St. Louis.

“The film is structured in a self-conscious kind of formal way where the image and sound are in conflict with one another throughout the entire film,” Harris said.

Why the film flew under the radar upon its 2000 release cannot be determined for sure, but Harris said popularity was never his primary concern.

“As much as I enjoy the recognition, even if it’s belated, I have to say that’s not why I made the work,” he said. “I made the work out of — for lack of a better way to say it — out of love. Don’t get me wrong, I want people to see the work and I want it to have a positive response, but that’s secondary to the act of making the film and the reason why I made it.”

Both UI filmmakers found success through making experimental films that brought their visions to life without focusing on whether it would become popular or critically acclaimed, or even fully understood. Success came second.