Instrument-producing furnace furthers the development of magnetic field and space exploration

A furnace developed in the Van Allen Hall is producing instruments key to magnetic field research and space explorations. The research conducted by David Miles and others has made the UI the new source of fluxgate magnetometers and tools to measure precise magnetic fields.

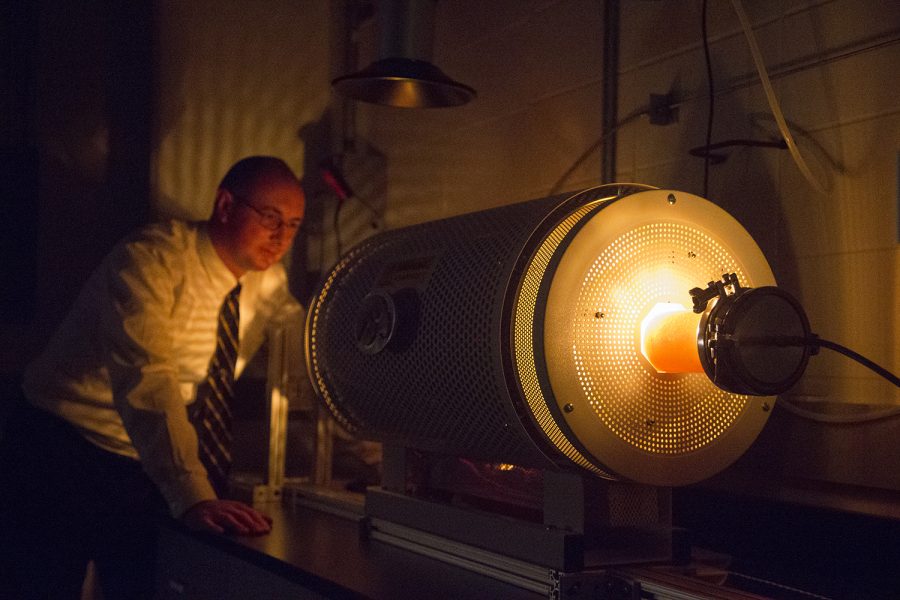

Space physicist David Miles is seen with a furnace that melts metal that is part of an important magnetic field instrument on Friday, May 3, 2019. The fluxgate magnetometer is used for measuring low-frequency magnetic fields during space missions.

May 6, 2019

Van Allen Hall is home to advancements in science and space exploration that have changed the field of physics and astronomy in major ways. Recent developments of an instrument-producing furnace by University of Iowa researchers continues the legacy and effect that the university has had in space.

David Miles, a UI assistant professor of physics/astronomy who was the head researcher in the development of the furnace, said the metal produced inside is a key part of an instrument called a fluxgate magnetometer. Fluxgates are used to study the magnetic field in space, and the furnace allows him to manufacture extremely sensitive detectors, he said.

“All of the detail and the drama of the furnace is just to build a little particular piece of metal that allows us to pump the field without adding new noise [that] will contaminate the thing that we’re trying to measure,” he said.

The furnace, Miles said, was a condition of his hiring at the UI in 2017. Without the furnace and its capabilities, he said, his work as an experimentalist would not be very useful, and he would not have the ability to create instruments used for space exploration, such as the fluxgate magnetometer.

RELATED: UI physicists receive $1M grant from NASA

The furnace can reach temperatures of approximately 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit, and it takes about five hours to go from room temperature to the temperature at which metal can be melted, Miles said. At these high temperatures, the melting metal produces a rosy-red glow that fills the room, indicating that the temperature in the furnace has reached its peak. From starting temperature to the cooling down period, the whole process takes around 11 hours, Miles said.

George Hospodarsky, an associate research scientist in physics/astronomy, is working on a project with Miles that uses the capabilities of the furnace. Hospodarsky works with higher frequencies, while Miles work with lower frequencies and zero frequencies. The project is working to build a sensor that measures both high and low frequencies at the same time.

Hospodarsky said the furnace allows UI physics/astronomy faculty and students in-house capabilities that previously were not available.

“The magnetic materials we use in these sensors allows us to do things at the university that, in the past, we would have had to hire a company or send them someplace else to do,” he said.

The new capabilities of UI researchers, students, and faculty to create magnetometers and magnetic cores is something that has not been worked on since around the 1960s, Miles said. With the development of this furnace, that research is now being advanced at the UI, he said.

UI physics/astronomy Professor Craig Kletzing said the UI and Miles have become the source for this kind of research because previous developers of magnetometers are aging and running out of resources.

“What’s most exciting is that this is an ongoing effort … as we get as we get this all up, and working at full capacity, and work things out and everything, he’s going to be able to make the best magnetometers around,” Kletzing said.

The research and instruments made with the furnace allows researcher to develop world-caliber instruments capable of aiding both national and international space missions, Miles said.

For any space mission, he noted, good measurements are needed, and developments done at the UI can provide instruments to do so.

“We’ve had excellent support from all levels of the university to make it happen … this was something that we wanted to do as a condition of my hiring, and the university absolutely delivered on that,” he said.