Banerjee: Political obligation in a post-McCain world

In light of Sen. John McCain’s death, it’s necessary to re-examine how we discuss and look at the lives and legacies of political figures, because blind adoration is no better than tasteless defamation.

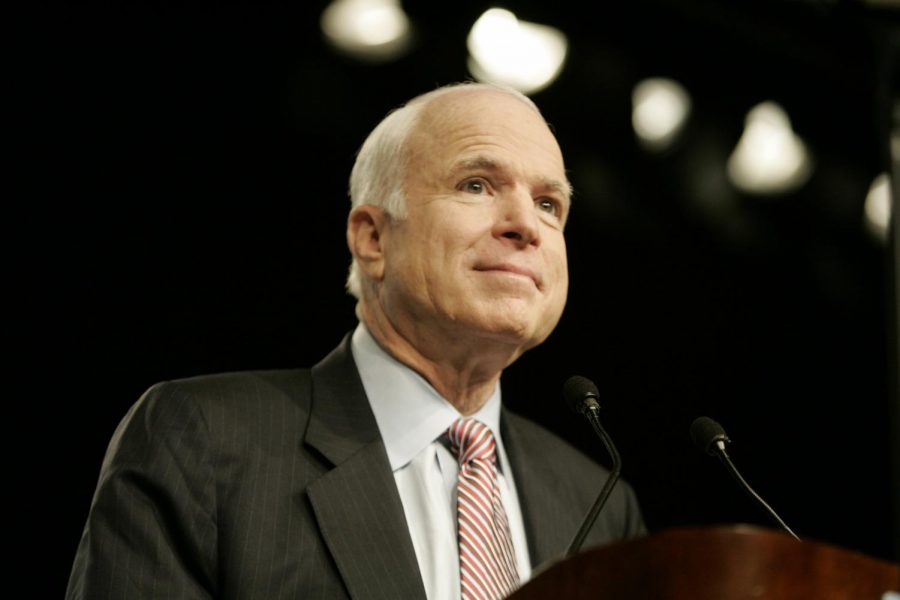

Sen. John McCain receives the applause from the audience before beginning a foreign policy address to the World Affairs Council in Los Angeles in March 2008 at the Westin Bonaventure Hotel. He talked about a collaborative foreign policy with input of allies abroad that differs from the go-it-alone approach of President Bush. (Annie Wells/Los Angeles Times/TNS)

September 3, 2018

On Aug. 25, prominent Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., died a day after his family announced that he would no longer receive cancer treatment. The senator had long made his career on the basis of providing civility to American politics; he was the Senate’s “maverick” in the face of purely partisan politics.

In the days following his passing, a liberal-slanted ethos has taken control of mass media, singing praises and eulogies to the face of “commonsense” conservatism. Many have already argued that with death comes a certain obligation to preserve the “dignity” of the deceased from the public. However, in doing so, it strips the effectiveness of political discourse and, ultimately, removes McCain from any responsibility for his actions.

This is not to say that inflammatory discourse concerning his personal life is a necessary evil, but rather the opposite. We owe it to any sense of democratic patriotism that McCain held to maintain vocal and civil discussion concerning his politics. His position was one that affected thousands of people, and, by doing so, he forfeited a right to total privacy under the eyes of the American public. An open and honest discussion of McCain’s actions — including his implications in imperialistic and militaristic policies — is necessary to adequately perform our duties as informed citizens of the United States.

For what it is worth, McCain seemed to be a model American politician in many ways. Admirably, he often attempted to cross the aisle, believing in the power of the American government as being a body for and by the people rather than for specific parties. Especially toward the end of his life, he saw a great need for unity in the American government, and his attempts toward that were striking in context with the larger political atmosphere. His work helped to open an important distinction between party politics and American politics.

However, our notion of his nonpartisan unity is inherently both American- and Western-centric. As McCain performed the role of the two-party system’s personal “maverick,” he was also implicated in a number of extremely distasteful, violent, and hateful acts. His “commonsense” rhetoric was only the logical choice in the face of the openly spiteful politics professed by his extremist contemporaries — this did not make McCain an egalitarian by any means. What makes McCain stand out in a Trumpian America is not just his good acts but his good façade.

It would be remiss not to mention that his renegade persona led to a policy of imperialism of such enormity that it harkened back to “Big Stick” Theodore Roosevelt himself. (McCain attempted to compare himself to the 26th president as well, saying in a 2002 speech that “Theodore Roosevelt is one of my greatest political heroes. … Roosevelt’s Americanism exalted the political values of a nation where the people were sovereign.”) Thrust straight from military backgrounds into the fighting grounds of the Senate, McCain held fast to his military ways for most of his career: while he never got to “bomb, bomb, bomb Iran,” as he wanted to during his presidential campaign, he did attempt to pull the U.S. into any possible military adventure, whether it be in Afghanistan, Iraq, Yemen, or, more recently, Syria.

Imperialism has always played a major part of American politics. The vulgarities that the current president spills on a weekly or daily basis are not so different in truth from the vulgarities that his predecessors took part in but never divulged so openly. When people talk of returning to the respectable politics of McCain, they are mourning the loss of private imperialism, of civilized brutality, of heroic war crimes. We do not want to be so violently shoved into the realities of our actions.

McCain played an important role in the American political stage, but to forget his past in our scramble to avoid President Donald Trump is a dangerous game. Despite the public feud between McCain and the president, he voted in line with Trump 83 percent of the time, according to FiveThirtyEight.com.

In a similar manner, even former President George W. Bush has been romanticized in the American eye, stripped of his responsibility to the people of the world to make up for the warmongering in which he took part while in office.

To accurately examine the life and legacy of a figure such as McCain, we must first acknowledge his fallibility and move on from there. This means that providing the dead with a grace period before we begin to analyze and understand what their actions meant for the world is impossible.

We cannot afford to forget our past as we continue to fear our future.