Researchers are working to learn more about factors other than smoking that increase a person’s risk for developing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

A recent University of Iowa study appeared to show a correlation between a genetic variation in lung anatomy and the risk of being susceptible to COPD. According to the UI Carver College of Medicine, COPD is the third-leading cause of death worldwide. There are 16 million people in the United States diagnosed with the disease.

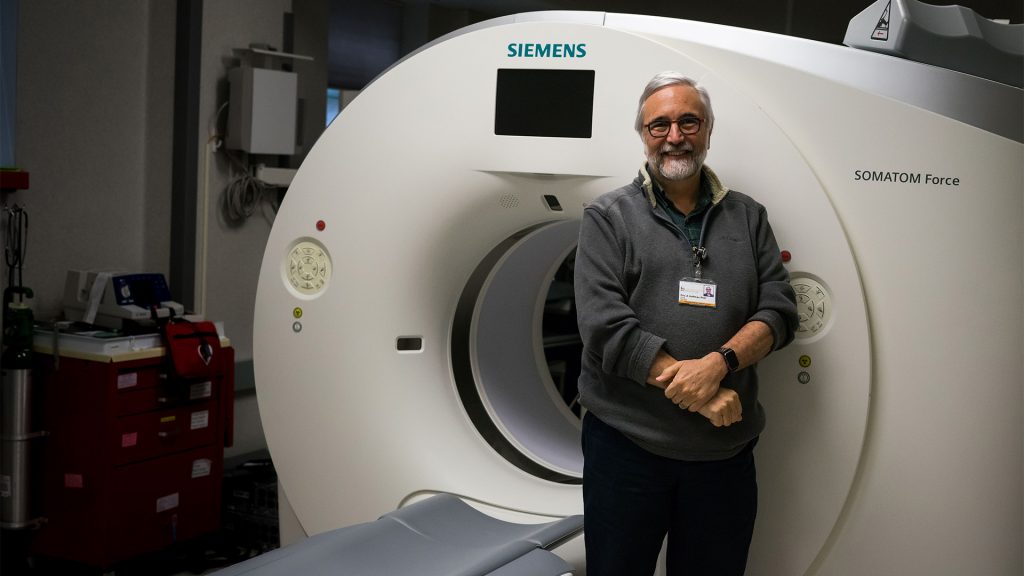

“The study was funded by the NIH to identify markers of various sorts that will break down the population of smokers that get COPD, and break them down in subgroups with the idea to find interventions,” said Professor Eric Hoffman, the director of the UI Advanced Pulmonary Physiomic Imaging Laboratory.

This study began to identify the traits that differentiate populations with COPD and to see how quickly these traits change.

“If there is a trait that is differentiating, and changing quickly, you don’t have to study them for 10 years,” Hoffman said. “You can study them for a short period of time.”

The UIHC General Hospital was chosen as the site to oversee the imaging portion of the study. The team devised protocols and gathered images through Volumetric Image Display and Analysis, an organization born in the UI.

RELATED: UI cancer center receives NCI grant for tobacco cessation

The data were collected and analyzed at Columbia University, where researchers discovered that there was an airway branch missing in some subjects and was extra in others.

“We saw that 25 percent people have one of the other variants,” Hoffman said. “We then started thinking about how these variants could put the subject at risk of getting COPD.”

The verifications revealed that a subject was about 1.7 times more likely to get COPD if the he or she had one or more of these variants, Hoffman said.

Even for those who did not smoke, researchers also discovered that if a participant showed one or more of these variations, their siblings had one of these variants as well, revealing a genetic correlation.

“This suggests it puts you at risk even if you inhale any abnormal substance — for instance, pollution,” Hoffman said.

Currently, researchers are working on a mouse that was created with this genetic variant and gets the abnormal pattern with the airway treatment. There is evidence that the mouse is more susceptible to COPD, Hoffman said.

“Together, these findings suggest that variations in airway-tree development may contribute to the COPD that we see later in life,” Ben Smith, an assistant professor of clinical medicine at Columbia University, said in an email to The Daily Iowan.

“More research is needed to determine if COPD that is associated with airway variation has a different prognosis from COPD due to smoking, which may help target treatment strategies,” he said.

RELATED: COPDGene study receives five-year renewal to continue 10-year follow-ups

There is a possibility that individuals with airway-branch patterns are reacting differently to inhaled medications. They can be more or less susceptible to air pollution.

Researchers are exploring this using computation fluid dynamic modeling of particulate deposition in the common airway branch variants, Smith said.

This study is important as it helps researchers identify individuals with risk of COPD by looking at their lung anatomy, said Alejandro Comellas, a UI clinical associate professor of internal medicine.