It was midnight, and Peter was racing against time to complete his assignment.

Feeling the heat, the University of Iowa junior and economics major decided to copy his friend’s work.

“[I cheated] because it was the last resort, and I was worried about my grades, and also because I was afraid of failing, and grades are important [to me],” he said, recalling the incident.

The next day in class, Peter, whose name has been changed for anonymity, was led to his professor’s office to

discuss what happened. Eventually, he and his friend ended up failing the class.

Though he is now fully aware of his actions, Peter said he didn’t initially know collaborating with a friend was an academic offense.

“It’s probably my fault that I didn’t read [the Honor Code],” he said. “I think there are a lot [of students who cheat], but they don’t end up getting caught.”

“It’s probably my fault that I didn’t read [the Honor Code],” he said. “I think there are a lot [of students who cheat], but they don’t end up getting caught.”

***

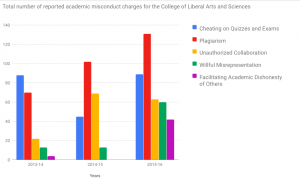

Whether it’s stealing a glance at others’ work, using ghostwriting services, or engaging in unauthorized collaboration, academic fraud continues to be a common problem on many college campuses across the nation, including at the UI. Here, academic misconduct cases have not only increased by nearly 69 percent in the College of Liberal Arts & Sciences, but also in the Tippie College of Business, where the increase rose around a whopping 121 percent.

Combating this issue isn’t so easy, as revealed in a yearlong investigation by The Daily Iowan.

Academic-misconduct trends

In total, 75 cases of honor violations were reported at Tippie in the 2015-16 academic year, up from 34 cases the year earlier, according to data provided to the DI. These could include cases of cheating, unauthorized collaboration and plagiarism.

In the College of Liberal Arts & Sciences, 386 cases were reported in the 2015-16 academic year, up from 229 cases the year earlier,according to a document obtained by the DI through a public-records request.

The apparent spike in reported cheating cases may be attributed to the emergence of companies that target students — largely international — with offers of ghostwriting and taking online tests. One UI official notes these companies have become even more aggressive at marketing services.

“The problem is we can’t go after these companies; they are not U.S.-based, they’re not tangible, necessarily,” said Kenneth Brown, an associate dean of the Undergraduate Programs for the business school, who notes that according to the IP addresses of these companies, many are based in Shanghai — making it hard for U.S. institutions to hold them accountable. “Really, what we can do is work under the realm of our institutions.”

Academic misconduct is not a theoretical question for the UI. The school was a target of a national media investigation inv

olving academic fraud last year. In fact, the Reuters news service revealed that the university investigated a good number of international students at the UI for cheating.

The investigation, which was further confirmed in a news report in the Iowa City Press-Citizen, found that UI officials were investigating possible academic misconduct involving at least 30 students enrolled in online courses — and a few sources Reuters spoke with indicated that the number could have been two or three times higher.

The UI had been notified of possible cheating through ProctorU, a national service that provides identity verification for online courses, according to the Press-Citizen. The company warned the UI that students may have attempted to cheat by having other people take their exams in one or more courses.

International students could be more susceptible

Unlike their domestic peers at the UI, international students were, and could continue to be, targeted by contract cheaters — paid ghostwriting services, which have been aggressively pursuing students. Last year, the UI International Students Scholars and Services sent out a mass email to students reminding them to stay away from said services.

“… Unfortunately, international students can often be targeted by people who may try to take advantage of them,” the email stated. “If you are ever presented with information about what you can and can’t do, or are given offers for services that you think may be questionable, don’t hesitate to consult an ISSS adviser.”

Several Chinese students interviewed by the DI had received mass emails in Mandarin Chinese from a paid ghostwriting company that was offering its services.

One such student, Chengchen Li, a UI senior from China who is majoring in biology, said she frequently receives numerous advertisements for ghostwriting services.

“I’ve been seeing a lot of advertising about it — every day,” she said. “I got it from [my] email and Chinese social media [such as] Weibo. As long as they locate you in U.S., the advertisements will automatically pop up — and you can’t avoid it.”

Another person, Yihao Zhang, a former UI student from China who graduated in December 2016, said he believes cheating at the UI is more frequent than people believe.

“I’m not going to say a majority, but many Chinese students are actually cheating,” he said. “I’m not going to throw any numbers because I don’t have any scientific way to prove that, but a fair number.”

Academic-misconduct detection — is the system perfect?

When it comes to dealing with academic misconduct, Brown said, he agrees the UI “can and should do more.”

“Could we have prevented this? I don’t know. In a big institution like this, you can do everything, and there would still be people who try to circumvent the rules,” he said. “Our job is to create a system that prevents it as much as possible. Educate people to not even be willing to be consider it.”

Although the current system isn’t without problems, Brown said, the UI always looks at ways to improve it.

“No system we have is perfect or complete, and what we need to do as an institution is just constantly be asking, ‘Is there more we can do?’ ” he said. “And I think in this area, what we want to do is ask, ‘Is there more we can do to educate faculty about how to run classes in ways that encourage academic integrity, and when there are severe violations, to catch it?’ ”

Tricia Bertram Gallant, who serves on the executive board of the International Center for Academic Integrity — a group of learning institutions based at Clemson University in South Carolina, that is committed to combating cheating, plagiarism and academic dishonesty in higher education — said reducing contract cheating can be a “complicated” subject.

“We can’t stop all cheating … so there are those things on the institutional level that are frankly not going to change, most likely,” she said. “What can change a bit more easily is the culture on campus, and that’s not an easy thing to do.”

After last year’s investigation into academic fraud at the UI, Brown said, several measures were taken to prevent cheating in online courses. For instance, Tippie’s “template syllabus” was modified. He also said a system comparing biometric measures associated with keystrokes was also utilized to detect students who were cheating.

“We can stop people from entering a classroom and advertising their service — but if companies are advertising on WeChat directly to students, or Facebook, or emails, we can try to set up spam filters, but at some point, we can only protect the students so much,” he said.

While the continued presence of academic fraud may be concerning for some, Brown said his concern is carrying around the assumption that no one is cheating. Instead, he said, acknowledging and coming up with ways to prevent and discourage it is necessary.

“That’s one of the conversations we are having; how do we do that in a cost-effective way,” he said.

Catching cheaters, however, shouldn’t be the main focus of the issue, said Kathryn Hall, the senior director of Curriculum & Academic Policy for the liberal-arts college. She said it’s equally as important for students to recognize the value of an education.

“We’re not in the business of catching cheaters — that is, we’re not a legal system, we don’t have laws, we have a code of ethics,” she said.

Academic-misconduct policies

Adding to the confusion, the UI colleges set their own policies and procedures related to academic misconduct.

“I think it would be great if we all had the same policies … it’s a lot for each of us to do separately, and it does make sense if we were to do it together instead,” Hall said.

However, she also cited a few downfalls with the idea of streamlining the policies. One, she said, is that it might be harder to educate faculty on the issue from a centralized position.

As a result of the confusion, behavior that could end in expulsion at one college could only be a warning at another.

Instructors are able to fail any assignments that show evidence of academic dishonesty. They may also fail a student for the course with permission and consultation from the college, according to the liberal-arts school website. The college may add consequences.

For instance, according to the liberal-arts college website, a first offense will require students to take a seminar of academic integrity costing $100 before registering for classes in their next semester. A second offense will result in suspension for one academic semester, and a third offense will result in expulsion from the UI, the website states.

“We try to contextualize the offense, because we don’t want people to feel utterly destroyed because they are being suspended for a year … we don’t want them to do it again, but we want [them to know] that we’re giving them a second chance, but they cannot repeat their mistake,” said Helena Dettmer, the associate dean for Undergraduate Programs & Curriculum and the Humanities at the liberal-arts college.

Tippie operates in a similar, but not identical, way. Students who violate the honor code in the business school will face possible sanctions ranging from getting a zero score to failing a grade in the course.

“Think of it as layers: Here’s the professor, the class, here’s the college,” Brown said. “With a first offense, we provide additional education by providing a letter, and I offer to meet students.”

For a second offense, however, he said, students are required to take a $100 academic-integrity seminar, in addition to meeting the associate dean of the college. A third offense involves suspension.

Faculty’s role in fighting academic misconduct

Overcoming academic misconduct would be impossible without the assistance of faculty members who witness cheating.

Brown said faculty are encouraged to use Turnitin — an academic-plagiarism checker technology for teachers and students — to detect academic misconduct.

“We provide a little bit of information about that in faculty orientations, but largely we rely on faculty to interpret those in the context of their own courses,” he said.

Annette Beck, the director of Enterprise Instructional Technology for the UI Office of Teaching, Learning, & Technology, said approximately 1,300 instructors used the Turnitin ICON integration last year. Additionally, roughly around 9,000 courses, including different sections of the same course, used the software in 2016.

However, that technology might not be enough to completely overcome plagiarism. Jason Chu, the education director at Turnitin, said the company only compares student papers to content from its databases, which may include past student papers, publications, and material on the Internet.

“The one important thing to know is that there’s no technology out there that is able to identify plagiarism,” he said. “[Turnitin is] a great way for faculty and students to check if that content has been used appropriately. So ultimately, any decisions around poor paraphrasing, intentional plagiarism, inadvertent plagiarism — all that comes down to your professors.”

To avoid plagiarism, Brown encourages faculty to have writing assignments uniquely tailored to their respective classes, stressing that generic prompts are the likeliest and easiest to be plagiarized.

“[A unique assignment] makes it very difficult to go online and to say ‘Hey, I want an essay,’ ” he said. “That’s a way that we get — not around the issue — but that’s a way we make it sufficiently difficult. But you’ve pinpointed one of the hardest areas for us.”

Bertram Gallant echoed that belief. She said it’s important for faculty to design assessments to be more personal and meaningful, so students may be less inclined to cheat.

However, she said, it’s important for the majority of students, who don’t cheat, to speak up about the issue.

“I wish the majority of students would step up and stop being silent about this,” she said. “Because they know it’s going on, but they don’t do anything.”

Frank Durham, a UI associate professor of journalism, said for him, the decision to report cheating depends on the weight of the offense.

“Two students reported the same work, and I reported it, but then it turned out to be a big mess because all I needed to say was, ‘Don’t do that,’ ” he said, recalling an incident in which he had reported a student. “Sometimes, I think following the policy too closely can cause an overreaction. I regret doing that; I think I made a mistake.”

In such instances, Durham said, it’s important to recognize that faculty members are humans, too, and they might need time and experience with the policy to understand how to interpret it. He said although the policy is written in a strict language, not everything that happens deserves punishment. But for one faculty member, academic misconduct may be attributed to students’ lack of understanding of the policies. Russell Ganim, the director of the UI Division of World Languages, said the UI and the liberal-arts college can do a better job at educating students on policies related to academic misconduct.

“What I have noticed is that students don’t always understand [the policies],” he said.

He noted that although the policies are stated in the syllabus, there is little reassurance on whether students review it again or if faculty restates the codes in class.

“We can’t just look at policies regarding academic dishonesty … they need to be integrated into our curriculum and into specific assignments,” he said.

Additionally, Ganim said, he believes training faculty in dealing with academic misconduct is an area the UI can improve on.

“I think we can have more workshops, video tutorials, online resources, readily available to students and instructors,” he said. “Maybe they already exist, but they aren’t applied as closely as they could be.”

Academic misconduct depends on colleges

The probability of students cheating also depends on the types of courses students are enrolled in. Durham said he doesn’t see many cases of cheating in the journalism school.

He attributed that to the way assignments are prepared and constructed in the School of Journalism & Mass Communication — timely and not necessarily repeated assignments.Patrick Dolan, a lecturer in the UI Rhetoric Department, said he hasn’t seen any recent cases of academic misconduct in his area. He, too, said he believes it probably depends on the type of classes students are in.

“For my class, the students will talk in class about what they want to write about, usually without forewarning,” he said. “One of the classes, they have to write a proposal … so I’m with them throughout the process, [and] the opportunity to do something … would be more work.”

Durham said that while it is easier to track cheaters for assignments, he was less convinced about exams.

“As far as giving exams goes, you just have to write new questions, either rewrite questions — but questions should be fresh,” he said. “If you just reuse exams over and over, you are inviting cheating.”

Unlike other issues in higher education, academic fraud is less likely to get the awareness it deserves because of the lack of immediate “bodily harm,” the Center for Academic Integrity’s Bertram Gallant said.

“The issues that rise to the top of our concerns are ones that threaten our immediate survival, so things that cause physical harm,” she said. “Our [inability] to show physical or economic harm does [prevent] getting attention on this matter.”

To counter academic fraud, each year, the center holds annual conferences to facilitate conversations on academic integrity, according to the center’s website. It also has an institutional toolkit to help combat contract cheating.