By Claire Dietz

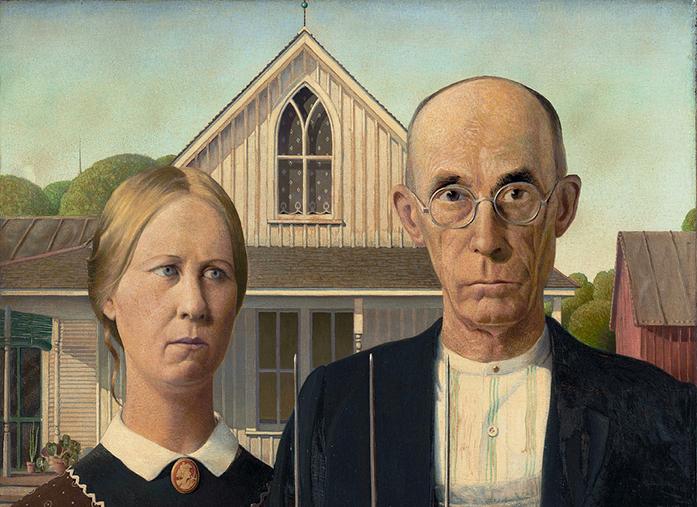

Grant Wood has a legacy in Iowa City, as a former art professor at the University of Iowa and a veritable icon of the American art movement in the last century. Now, more than 70 years after his death, his legacy is carried on through the Grant Wood Fellows.

The Grant Wood Fellows will culminate their year in Iowa City with an exhibition reception today at 5 p.m. at the Carlo Bar at C.S.P.S., 1103 Third St. S.E., Cedar Rapids.

The process of finding the Fellows begins with faculty in the School of Art & Art History and the Division of Performing Arts conducting an international search, and the Grant Wood Art Colony attracts premier artists to come to the university to work with students and nonstudents alike.

The three Fellows this year are Christopher-Rasheem McMillan as the performance-art fellow, Tameka J. Norris as the art fellow, and Colin Lyons as the printmaking fellow.

Maura Pilcher, the director of the Art Colony, describes the exhibit as a cohesive exhibition with materials ranging from aluminum scaffolding to braided paintings.

“The artwork on display was made for this location and for this moment in time, and it will never be experienced again,” she said.

Printmaking, in particular, has a long history at the university, with 2016 witnessing the passing of printmaking pioneer and longtime UI professor Virginia Myers.

Lyons, however, is not what could be called a printmaker, at least in the strictest sense of the word. Instead, he uses his printmaking as a vehicle for his larger artwork.

Right now, something that seems to inform a lot of his work is geoengineering and the larger effects of climate change.

“The right [wing] doesn’t want to talk about it because it doesn’t mesh with climate-change denial,” he said. “The left [wing] doesn’t want to talk about it because the existence of it would give someone an out clause, it wouldn’t be necessary for someone to do anything.”

His installation at C.S.P.S serves two functions. It is the culmination of his work here as a Fellow, but it also serves as a proposal for Cedar Rapids to make this a permanent exhibition in the community.

“The idea, the project is called Contingency Plan, is taking the idea of geo-engineering and bringing that into the context of the landscape,” Lyons said. “I’m building this cooper-plated scaffolding and a vessel containing an iron-sulfate solution.”

On his website, Lyons describes the piece as such:

“In collaboration with the engineering department at the University of Iowa [Rick Fosse and Jeff Crone], I have developed a printmaking-based iron-fertilization prototype that employs the industrial debris left over from demolition efforts at the nearby Sinclair meatpacking facility. This prototype will convert the site’s industrial waste into iron sulfate, the primary ingredient in ocean fertilization geo-engineering projects. As such, the site-remediation effort for this urban brownfield will be built into the creation of the monument itself.

“The iron-sulfate solution will be stored in etched glass capsules, perched at the 1,000-year flood level, atop copper-plated scaffolding. In theory, these capsules should not be released until around 3008 (or more accurately, each year, they will have a 0.1 percent chance of release). If the river breaches this catastrophic level, a valve will open, releasing the contents into the Cedar River, leaving a trail of phytoplankton in its wake. However, as we’ve witnessed so recently with a 100-year flood closely followed by a 500-year flood, we live in an age when the acceleration of history moves toward a vanishing point.”

Although 3008 seems a long ways off, Lyons is interested in some ways to see how this may very well live beyond him. There will be an evaluation done of the sculpture’s environmental stability in the next few decades. If the sculpture or its facets are found to be ineffective, the value will be shut, and remain only as art.