By Isaac Hamlet

Marital problems happen. Sometimes, they stem from a lapse in communication between partners. Sometimes, they occur because of unforgivable infidelity, or sometimes, the spark simply goes out.

Sometimes, however, one partner is busy working on the creation of a future staple of modern-day science, while the other is trying to point out the advances being made are built on unethical practices and should be reconsidered, thus sparking a moral dispute that pulls numerous relevant scientific figures into the fray.

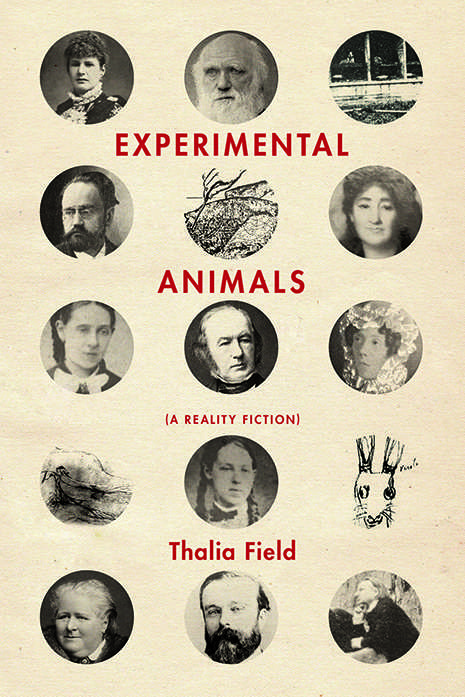

Such was the case for the French physiologist Claude Bernard and wife Marie Françoise “Fanny” Bernard, the subjects of Experimental Animals. Author Thalia Field will present her new, essayistic novel at 7 p.m. Friday at Prairie Lights, 15 S. Dubuque St.

“This is a hybrid fiction and nonfiction novel that looks at the creation of the laboratory,” Field said. “The origin [of the laboratory] was not institutional; the movement was led by renegade scientists doing experiments in their homes, in their apartments, under stairways. You could hear these animals they were experimenting on wailing through the streets of France.”

Claude, because of these practices, helped establish the idea of laboratories as well as the principles of experimentation. However, these advances didn’t negate the animal cruelty taking place in the experiments, something Fanny was vehemently against.

Both sides garnered advocates, and the ensuing argument pulled in characters such as Charles Darwin.

“[Claude] would set up his lab to do experiments on animals, and she’d steal the animals,” Field said. “This is sort of the first wave of fanatical radicalism on the issue. They all think they’re right, and they’re all at opposite extremes.”

The book is told largely through documents from the historical characters. When she set out researching the movement, Field had hoped to use these documents exclusively. However, records from Fanny were unfortunately sparse in the archives.

“I originally wanted to do the book as a of letters written by these people,” she said. “But Fanny was too important to the narrative, and there was too much missing.”

Rather than abandon the project or Fanny, Field decided to fuse genres. Using the few documents she had from Fanny (mostly angry letters addressed to her husband), she created a voice for Fanny that she inserted into fictionalized reconstructions of scenes.

“It’s mostly factual, but I do some writerly sleight of hand to collapse the expanse of time during and between some events, which might be scoffed at by a perfectly quant historian,” Field said.

The events of the book focus on the lives of Fanny and Claude and subsequently cut off in about the 1880s. Yet, as Field points out, in a lot of ways the story gets “even wilder from there.”

“It’s not about a distant time and issue; it’s really something that persists into today,” she said. “I think the role of animals is not yet resolved. We’ll go around and around until we find a way to resolve it.”