By Tessa Solomon

Around 5 p.m. Nov. 4, I was walking down Washington Street when I passed two young women talking animatedly. Hungry and intent on reaching Osaka, where I was to have dinner, the duo only garnered a glance. But in that moment, once I got close enough to notice their black-framed glasses, the one’s buzzed head, and the other’s whipping blonde locks, I caught a distinct snippet of Russian chatter.

Like a pair of magnets suddenly exposed to their pole, my ears perked up; but it was too late, they had already turned the corner. Above me the Englert’s marque flashed, its bold blue lettering announcing PUSSY RIOT / JESSICA HOPPER.

At 7 p.m., seated in the Englert, I got a better look at the pair. At the long table sitting center stage, Pussy Riot’s Maria Alyokhina — wavy locks flowing from a black beanie — sat between Alexandra (Sasha) Bogino, a journalist for Pussy Riot’s news network Mediazona, and their partner and regular translator, Alexander Cheparukhin.

At the head of the table sat music critic and punk feminist Jessica Hopper, whose presence itself was an event. She guided the night’s conversation, touching on a variety of interconnected topics ranging from Putin to feminism in Russia and guerilla journalism.

The talk was given its context with a 13 minute clip from Act & Punishment, a documentary on Pussy Riot by Yevgeni Mitta. It traces group’s evolution from their early activism through the unfolding movement sparked by their “punk prayer performance” in the Cathedral of Christ the Savior.

In the video, crowds of thousands march through Moscow’s streets.

ART IS FREEDOM, their signs read. FREE PUSSY RIOT.

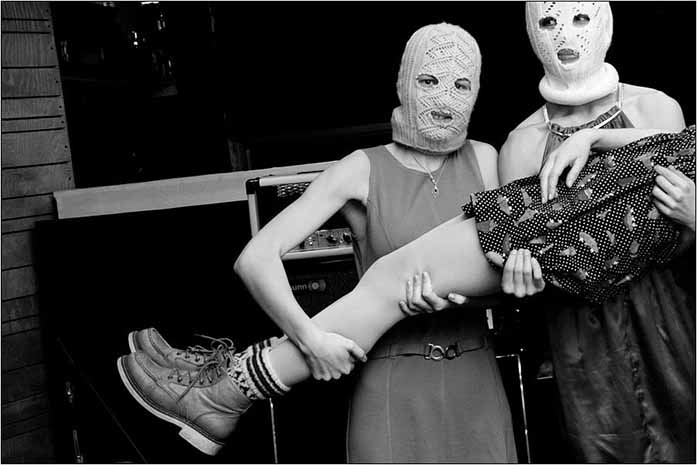

The group’s signature balaclavas — now an iconic face of contemporary punk activism — cover young, old, women, men. Bodies mosh, fists pump, mouths scream the “punk prayer.” The action comes across less as a riot than as an expression of deep, frightening frustration.

“In action, the most important thing is you only have one chance. So you need to be very prepared,” said Alyokhina, back at the Englert, in her husky, accented English.

Action, and an individual’s ability or inability to achieve it, quickly became a crux of the discussion.

Hopper asked Alyokhina about the play she was reportedly in the works of writing and staging in Belarus. More than a play, Alyokhina explained, the work also functions as an underground protest, staged in garages, always fearful of disruption by the police.

“The idea was to take the most frightful moments from prison and our so called “freedom” and going back to them 20, 30 times,” she said. “If you can go through and stay alive, you will stay stay strong.”

She and fellow Pussy Riot member Nadezhda Tolokonnikova both served nearly two years in prison as punishment for their “punk prayer” performance.

Alyokhina noted the important role their fans and those who saw merit to their cause played in the time the duo were locked up.

“If you don’t have public support [in prison], they can easily take your life,” Alyokhina said. “We’ve seen other women who had no support, and a lot of them came to us [and say], ‘You can do something because the world knows who you are.’ ”

The conversation then turned toward Mediazone, the independent news source Pussy Riot founded.

Hopper asked Bogino what it was like being a young journalist in Russia, to which Bogino — much to the audience’s surprise — laughed.

“It’s kind of fun,” Bogino said. “If you want to know what’s happening, you have to start in the courtroom.”

Mediazone works out of an unmarked office in Moscow. Always aware of the difficulty of freedom of expression in the Russian press, the group takes it upon itself to investigate criminal cases against outspoken activists and advocate their release and reform. Members of the small staff have been attacked, she said, and they constantly fear the police will raid the newsroom.

Toward the end of the hour, Hopper asked when and how they were introduced to feminism.

For Sasha, influence came through the consumption of foreign philosophies and cultures, spread through social media.

“It was like one day I knew I have rights,” she said. “Russia is too late with feminist ideas.”

Alyokhina braced the audience that her story was not as inspiring.

“When I was 18, I was pregnant,” she began, going on to detail the stigma around abortion in Russia.

“At the same time,” she added, with a palpable air of sarcasm. “If a woman decides to have a child she receives $30 per month for it.”

A disgusted grumble traveled through the audience

“It’s shit,” she said. “When I realized that, I started to read.”

Eventually, Pussy Riot was formed, and soon, the band became a symbol, and their song became an anthem.