Inspired by the work of modernist master Jacob Lawrence, Step Afrika aims to bring the stories of African American migration, heritage, and culture to the Hancher stage

By Isaac Hamlet

The stage is filled with an array of step dancers draped in cream-colored floor-length skirts. Brightly colored images — abstract streaks of black, blue, red, and yellow — decorate the screens at the rear of the stage as the dancers clap and high-kick in the shifting shadows of the blue-tinged overhead lighting.

Step dancing is a style of performance first developed in the early 1900s by African American college students who, in their movement, aimed to hark back to forms found in traditional West African dance.

Step Afrika, founded in 1994, was the first professional dance company dedicated to bringing this style of dance to the big stage.

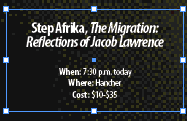

At 7:30 p.m. today, the Step Afrika troupe will stomp into Hancher to perform The Migration: Reflections of Jacob Lawrence.

The performance, originally created in 2011 but adapted for current times, is based on a series of 60 paintings (The Migration Series) made by modernist painter Lawrence between 1940 and 1941. The paintings depict the Great Migration, the movement of African Americans from the South to the North in search of more comfortable lives in the Jim Crow era.

“[Migration] is part of a history that I doubt the average American even knows about,” said Mfon Akpan, artistic director for Step Afrika and a performer in both this show and its 2011 counterpart. “Migration shaped the history of American culture. It led to the Harlem Renaissance and the spread of art and culture and dance.”

In the work of Lawrence, considered part of the second wave of the Harlem Renaissance, the members of Step Afrika found an ideal through-line for their commentary on race and the modern condition.

“[Lawrence] is a fascinating figure in the history of both American art, modern art, and African-American art,” said Joni Kinsey, a University of Iowa professor of art. “He’s not only a part of the African-American art historical context, he’s a modernist in a much broader way. He addresses things beyond his subject matter, a kind of searing portrait of midcentury life, both in Southern context, rural context, and Northern urban ones.”

The performance draws its inspiration, in particular, from the paintings in The M igration Series given to the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C. These works make up about half of the original series, with the other half currently residing in the Museum of Modern Art.

igration Series given to the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C. These works make up about half of the original series, with the other half currently residing in the Museum of Modern Art.

On stage, giant, blown-up images of Lawrence’s paintings are projected onto the backdrop as the dances are performed. Using dramatic lighting design, quick-hitting choreography, and a wide spectrum of color, the group mirrors and evokes the simple yet powerful figures in Lawrence’s art to bring it to life on stage — to give its heart a beat.

In its subject matter, the story covers not only the history of African-American migration, but also the evolution of music in the African American community. As such, the show doesn’t start at the time of the great migration; rather, it begins in the 1500s and then moves forward into the 1930s.

“Enslaved Africans had lost access to drums and other instruments, so they had to improvise them,” said Jakari Sherman, the show’s director and principal choreographer. “The drum was not used just for celebration but communication. This show is the journey of rhythm, of music, of sound in that community.”

Sherman directed the original Migration in 2011, before taking a hiatus from the group. But upon hearing that the company was planning on remounting the show, he was more than happy to come back to help shape the new iteration.

Part of the challenge Sherman faced in covering such a large period of history was making sure the through-line of the play was clear. To help with that, the performers wear costumes that change appropriately with the time period from scene to scene.

“You can see correlations on stage between the color palettes we’re using on the set and costumes and what’s in the art,” Akpan said. “It’s a really great merging of art forms.”

The larger variety of costumes is only one of the ways the show has changed since its 2011 performance. The show has brought in a saxophone player, flautist, and contemporary dancer to help the 11 step artists add to the flavor of the piece.

“I love merging dance and the visual-art worlds,” said C. Brian Williams, the founder of Step Afrika. “It’s even better that we’re telling the story of an artist who transformed the country.”

As Kinsey said, Lawrence mixed the disparate spheres of abstract art (art relying on shape and color rather than immediately recognizable objects or places) and figurative art (images clearly rooted in reality).

“He uses a lot of flat colors and patterns in his work,” she said. “He’s figurative in that he has recognizable subject matter, but he’s still very abstract. He’s dealing with the human condition through form, color, pattern, lines — no differently than other modernists even as he uses what’s called figurative representation to convey his message.”

Drawing clear inspiration from Lawrence’s cross-genre work, Migration often employs this radical experimentation in its depiction of the story’s recurring images, including the train. A vehicle with deep symbolic meaning, the train made the Migration possible by enabling black men to go north before their families did to secure land and establish the beginnings of a home.

“There are some beautiful moments in the second half of the show with the train,” Sherman said. “We move to simulate a train in the dance while using John Coltrane and his jazz music to inform the stepping. It’s a meeting place of a musical style and movement.”

If nothing else, that’s what the show is: a meeting place. Not just for “musical style and movement” but a myriad of other creative forms.

“If you see one thing this year, see this,” Williams said. “If you love dance, this is the perfect show for you. If you like history, this is a point in history that you might not have seen. If you like art or drumming or theater, we’re giving you some of everything.”