By Tessa Solomon

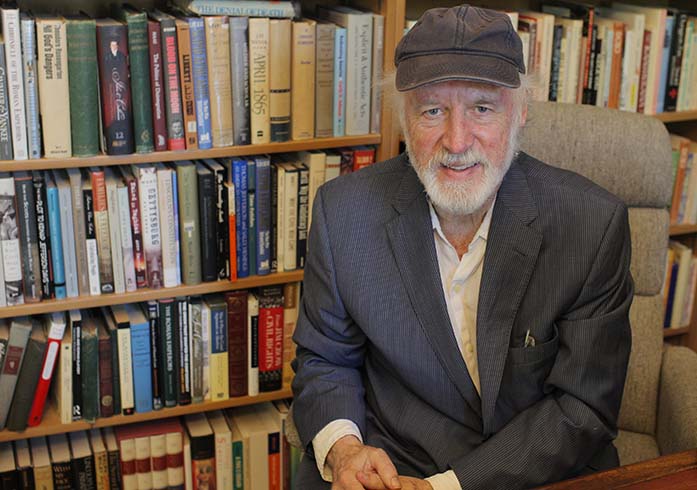

On Friday, Allan Gurganus — acclaimed novelist, beloved teacher, and former Iowa Writers’ Workshop student — will return to Dey House once again.

He will read from his novel in progress, The Erotic History of a SouthernBaptist Church, at 8 p.m. in the Frank Conroy Reading Room. Though his writing often contains meditations on the people and peculiarities of his first home, Rocky Mount, North Carolina, Friday’s reading will function as its own sort of homecoming.

“I think of Iowa City, Manhattan, and [Rocky Mount] as being my three homes,” Gurganus said. “So it will be very natural to be back in Iowa City. It’s like taking your own pulse, checking in with your former self.”

He thought back to when he was 26, a resident in the Writers’ Workshop, wandering Iowa City’s empty streets through the quiet night and early morning, reeling from the news that his short story, “Minor Heroism,” would be published in The New Yorker.

The amazement Gurganus experienced in that moment remained emblazoned on his psyche after all these years.

“I saw the difference between that first self and what it meant now to be an older, professional writer who is trying to fulfill his promise,” Gurganus said. “I’m almost 70, and I look back at the whole experience with no regrets, just gratitude that the Workshop wants me to come back.”

His first novel, Oldest Living Confederate Widow Tells All, released in 1989, quickly found its way into the contemporary canon. The sprawling work of fiction explores race, relationships, and manhood in the historical American South with Gurganus’s now-signature dark humor and deep insight into the human psyche. While the onset of the novel’s success was rapid — The American Scholar’s Robert Wilson proclaimed that Gurganus was “the rightful heir to Faulkner and Welty” — Gurganus refuses to rush his prose.

“Books should not come only when you’ve made insightful decisions about the way existence moves,” he said. “One of the things that is misunderstood about writing is that the only goal of writers is to produce books. The goal of writing is to produce listening.”

Gurganus attributes all profound fiction writing to everyday observation and an ability to track the conscious and unconscious motions of humanity. Waiting at a bus stop, he is acutely aware of even the most ordinary of sights, such as the man leaning, aloof, against a pole, his hungry eyes searching for that first glimpse of the bus.

These techniques are at work in his new novel, The Erotic History of a Souther Baptist Church. Set in his recurring, fictional village of Falls, North Carolina, it promises a probing investigation of the failings and salvation of a small-town ministry.

“It’s a fascinating assignment to a novelist to look at an institution over 70 years and see how it changes,” Gurganus said. “To take it under from its corruption, or give it a value or light that everyone responds to.”

He describes the plot — influenced by but not based on the contentious presence religion assumed in his childhood — with the affection and interest of a father nurturing his newborn. It is a comparison only made stronger knowing mortality is on his mind, a contemplation he is not entirely uncomfortable with.

“I don’t have children myself,” Gurganus said. “But when I look over the list of hundreds of students I’ve had, many of whom are well-known writers now, I feel like I’m looking at my tribe, my babies, my stake in the next generation.”