Tessa Solomon

Actor, author, and UI alumnus Gene Wilder, 83, died Monday at his home in Stamford, Connecticut. His nephew, filmmaker Jordan Walker-Pearlman, reported the cause as complications resulting from Alzheimer’s disease.

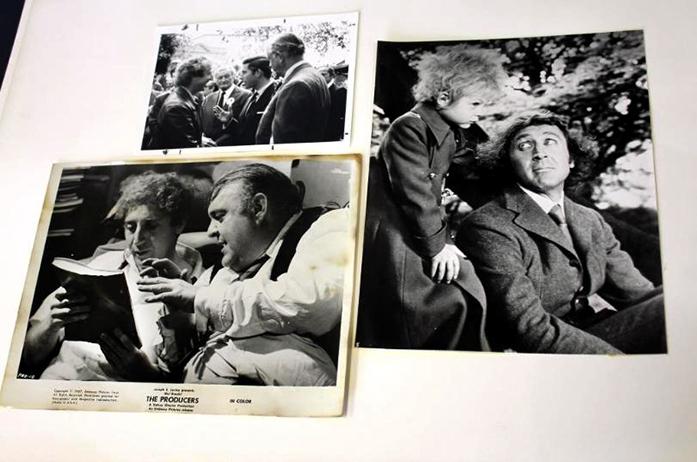

With his singular, gleefully manic energy, Wilder left cinema a legacy of iconic characters, most notably including accountant Leo Bloom of the The Producers (1968), wild-eyed chocolatier Willy Wonka of Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory (1971), and Young Frankenstein’s Dr. Frederick Frankenstein (1974).

His acting enthralled audiences since his big-screen début as an undertaker kidnapped by the titular bank robbers in Arthur Penn’s crime drama Bonnie and Clyde (1967). In the movies that followed, and most notably in his work with director and friend Mel Brooks, his performances — equal parts exuberant hysteria and quiet magnetism —cemented a style influenced by a personal struggle with mental distress.

Before adopting his stage name (inspired by Eugene Gant, the protagonist in Look Homeward, Angel and the playwright Thornton Wilder), he was Jerome Silberman, born in Milwaukee on June 11, 1933. The son of a novelty salesman and a Russian immigrant, he was determined by age 11 to make a career for himself on the stage. He entered the University of Iowa as a communication and theater major, ambitions and inspirations intact.

The Charlie Chaplin film City Lights, Wilder said in an interview, “made the biggest impression on me as an actor; it was funny, then sad, then both at the same time.”

For those who knew him, memories of when Wilder lived in Iowa City lean more toward the lighthearted. He rented a room at 420 N. Gilbert St., the home of the Cilek family. While already commanding lead roles in the UI theater, he delighted the Cilek children with impromptu performances.

“[Wilder] and his roommate would put on skits, and we would just roll on the floor,” said Iowa City native Mike Cilek. He recalls with a palpable fondness the days Wilder lived with his parents and his five siblings.

Though only 5 or 6 years old at the time, Cilek relates Wilder’s charisma, and, even more specifically, the vibrant crimson of Wilder’s convertible, a dashing car whose tank the young Cilek, pretending to be a gas station attendant, poured buckets of sand into.

Cilek wanted to make it clear, though, that Wilder treated the ruining of his beloved car’s tank with good humor.

A glimpse into Wilder’s life at, and after, the UI is accessible through the materials donated to the UI Special Collections archives. View scripts decorated with doodles, a penetrating 1955 senior yearbook photo, and an autograph adorning a quick, cartoonish self-portrait that captures his famously electrified hair.

“This is a person [who] has touched so many people with his movies that having a connection to things he’s touched brings people closer to that big Hollywood world … realizing that, for a brief time, he was just another student working on a degree,” UI Special Collections librarian Colleen Theisen said.

In one photo, a collegiate Wilder, intent before the mirror, applies makeup for a sophomore performance.

“It was before he became ‘Gene Wilder,’ ” Theisen said. “It’s a classic actor’s pose — putting on makeup before a performance — but it’s like he’s also getting ready for the rest of his life.”

That professional life was marked by screen triumphs, including an Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actor in The Producers and a Golden Globe nomination for his performance as Willy Wonka — and beloved roles in films such as the 1980 comedy Stir Crazy. A Hollywood renaissance man, Wilder also worked to develop his skills as a screenwriter, eventually winning, in 1975, alongside cowriter Brooks, an Academy Award for the script of Young Frankenstein.

Toward the end of his life, he turned his attention solely to writing, enjoying success as a novelist and engrossing audiences with his 2005 memoir Kiss Me Like a Stranger: My Search for Love and Art. In it, he relates a tumultuous relationship with his third wife, comedian Gilda Radner, an episode that included scenes of electroshock therapy at a psychiatric hospital, and a battle with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in 1999.

“He was a funny man, but he had a serious life,” Cilek said. “And I think we all need to step back and remember that.”

The turbulent events of his personal life frame his emotional performances in a new light, his trademark hysteria suddenly acquiring more concrete grounding. But one constant remains throughout the narrative of his life: a passion for each moment spent acting.

“What do actors really want? To be great actors? Yes, but you can’t buy talent, so it’s best to leave the word ‘great’ out of it,” Wilder said in an interview. “I think to be believed, onstage or onscreen, is the one hope that all actors share.”