By Ian Murphy | ian-murphy@uiowa.edu

Think back on the great Hawkeye football teams. Think as far back you can remember.

Those Hawks might be ones you’ve only heard about at the dinner table.

There were the Hayden Fry teams that restored the Hawkeyes to prominence. You may remember the 1986 Rose Bowl team, which as the then-No. 1 team in the country, took down then-No. 2 Michigan during the 1985 season en route to the Rose Bowl.

Now think back even further. To the time when men wore hats for style and to the teams of legends everyone knows. The presence you feel at Kinnick Stadium, that faint whisper that rises just above the frenzy of the crowd when the wind is blowing just right. There’s a magic at Kinnick Stadium. It comes from them.

There are the 1939 Iron Men, the team that put Iowa football on the map. It’s the team that produced Nile Kinnick, the eponym for the hallowed, historic brick and mortar monolith on Stadium Drive and the Hawkeyes’ only Heisman Trophy winner.

Then there’s a street that runs around Kinnick Stadium, named after arguably the greatest coach in program history, Forest Evashevski, “Evy,” as nearly everyone knew him.

You’ve heard of Evashevski’s teams, too. The 1959 Rose Bowl team claims the program’s only national title, as voted by the Football Writers Association of America (although the AP and coaches’ polls named LSU as champion). Hawkeye quarterback Randy Duncan has his No. 25 forever emblazoned on the press box at Kinnick Stadium.

But there’s another team you’ve probably never heard of. A team whose season mirrors that of the current edition of Hawkeyes, with a common opponent and so much on the line that the season hung on one game.

One game could spell the end of the playoff dream for the 2015 Hawkeyes, but one game ended the bowl-game aspirations of this historic team.

But this isn’t a story about the 2015 Hawkeyes, either.

This is the story of the Hawkeye team that reached the program’s first No. 1 poll ranking, the one that played games so exciting that The Daily Iowan’s football reporter estimated there were two heart attacks in the stadium during each home game

This is the story of the 1960 Hawkeye football team, a team with such high expectations, such lofty ambitions, that on opening day, Sept. 24, the headline under the DI masthead read “Football Takes Over Today.”

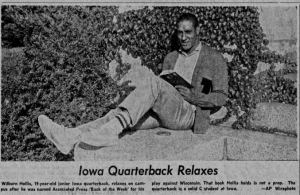

“We had some really really really really good players on that team,” said Wilburn Hollis, the starting quarterback.

DI sportswriters noted concerns entering the season including that the Hawkeye backfield would not be up to par, the Hawkeye youth would have trouble with depth issues on the line, and youth on defense would expose the Hawkeyes, not unlike the concerns this year.

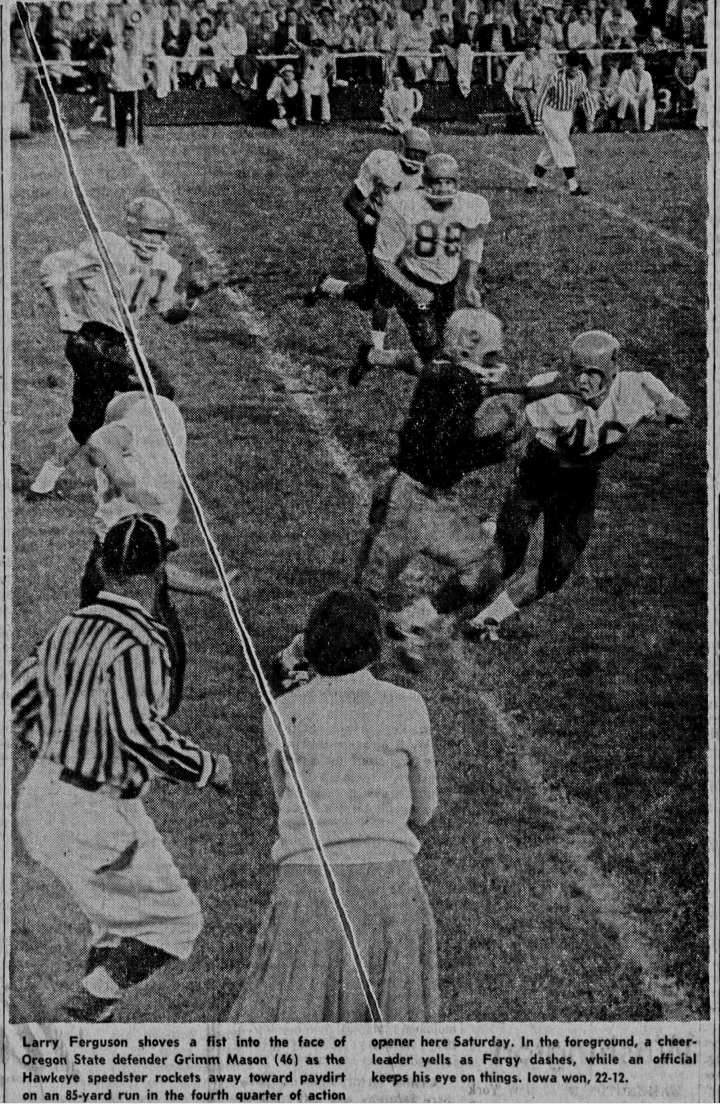

But on a perfect fall day, a 77-degree temperature and a light wind, the No. 19 Hawkeyes silenced the doubters, quickly, in a 22-12 win over Oregon State. Hollis, who said he was more of a running quarterback, was impressive, with his passes rocketing out of his hands, according to reports from the time.

Iowa climbed to No. 8 when the next AP Poll came out after the weekend. The climb didn’t stop there.

With Evy fighting a high fever, the fear among the faithful was that the coach would not be on hand for the next game, at Northwestern.

The worries were tempered when Evashevski patrolled the sidelines on Oct. 1.

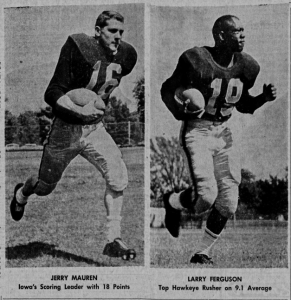

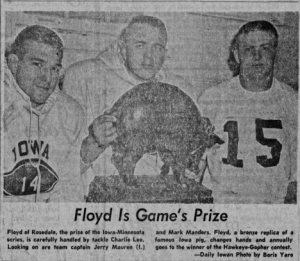

Evy was fine. Iowa scored a touchdown on a 45-yard run from back Jerry Mauren, and the rest of the game followed the script The Hawkeyes rolled the battered Wildcats in a 42-0 thumping.

After the game, Northwestern coach Ara Parseghian told DI football writer Allan Katz, “As of right now, I don’t think there is anyone in the conference who wilI be able to cope with [the Iowa running backs].”

The Iowa fleet of backs posed problems for the opposing defenses all season, again a similarity, but the quarterback said Northwestern was never much of a problem for the Hawkeyes.

“You’d have a team such as Northwestern, which was almost always a doormat, and they’d go down and beat them,” Hollis said.

With two wins under their belt, the Hawkeyes gained even more national attention, reaching No. 3 in the AP Poll.

Save for Northwestern, 1960 was as tough a year in the Big Ten as any. Every other Big Ten team the Hawkeyes played was ranked in the top 20.

As such, with the Big Ten race predicted to be tight, the Hawkeyes next targeted No. 13 Michigan State.

Down 15-14 late in the fourth quarter on Oct. 8 in East Lansing, Iowa fumbled the ball in its own territory and appeared to have given the game away to the Spartans.

In what would become a theme all season, the Hawkeyes got down early and had to battle their way back.

Back in Iowa City, some fans turned off their radios, assuming the Hawkeyes were done for, not learning the results of the game until Monday morning, Hollis said.

The season would have had much less importance if the Hawkeyes had quit when down.

“But we always found a way to come back,” the ex-quarterback said.

The Hawks did just that against the Spartans, edging them by capitalizing on a fumble a play later they returned 67 yards for the go-ahead touchdown.

Iowa did not trail the rest of the game and that, according to another former Hawkeye, doesn’t just happen.

“We were playing them up there in Michigan, at Michigan State Stadium, and the crowd was against us; it was a tough game,” former defensive tackle Alfred Hinton said.

“Had we not gotten that kind of unusual play, it just doesn’t happen; we wouldn’t have won that game.

“That Michigan State game was just back and forth, back and forth; it was almost surreal in a sense.”

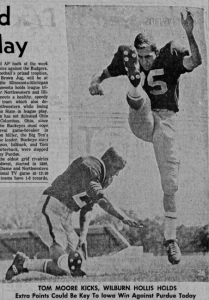

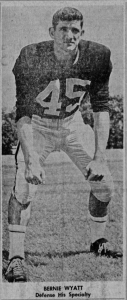

Michigan State then threw an interception to D-back Bernie Wyatt, and Hollis punched in a Hawkeye touchdown a few plays later. The Hawkeyes stole a 27-15 victory from what had looked like a sure defeat.

Iowa jumped to No. 2 in the AP Poll the following Monday.

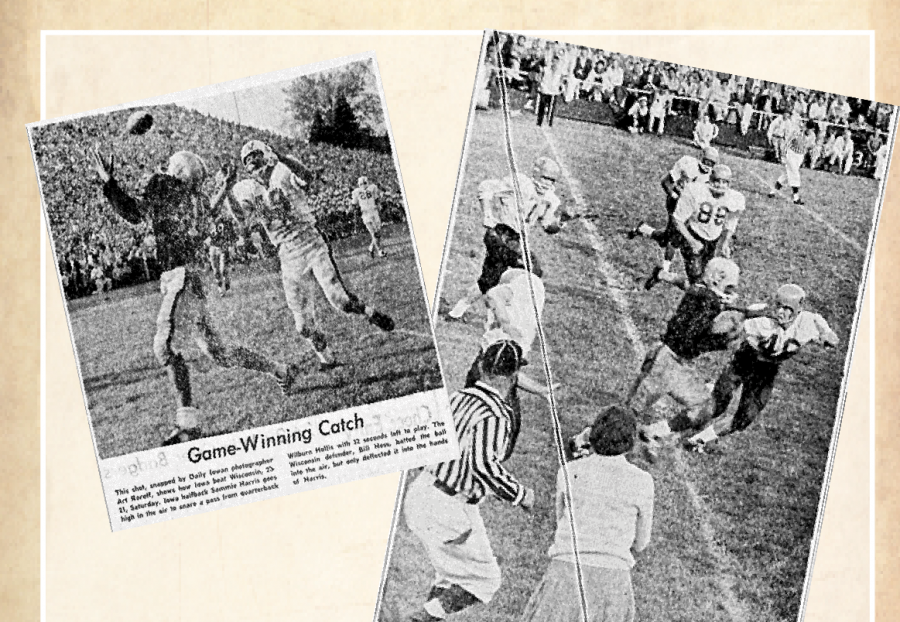

No. 12 Wisconsin came next, and the Hawkeyes didn’t blink. Hollis rushed for a pair of touchdowns and threw a late touchdown pass to Sammie Harris to give Iowa a 28-21 lead over the Badgers. Iowa did not lose the lead.

Four games into the season, the now No. 1 Hawkeyes were surprising everyone except the coaches.

Four games into the season, the now No. 1 Hawkeyes were surprising everyone except the coaches.

“Evy might have a bad rap,” Hollis said. “[But] the most emphatic thing I ever heard him say was confound it.

“If you messed up, they’d run you into the ground.”

Whatever Evashevski’s discipline was, it worked, although Hollis said the 6-2, 240-pound coach with massive arms hardly needed to discipline, in large part thanks to his size.

Former players said Evy had a knack for getting the most out of them, and it varied by each player.

“I could remember learning to play, and in one game, I was playing, and I got really blocked a lot and knocked back … and Evy saw that … he saw my mistake, and in the meeting, I think it was Sunday or Monday, he kept running that mistake back and forth in slow motion,” Hinton said.

Evashevski told Hinton if he kept getting blown back like that, the backup would take over his spot.

Hinton made sure the mistake did not happen again.

“If you get knocked on your ass again without playing well or playing hard, you’re not going to play,” he said. “He knew people, and he knew the players, and he knew what to say to you to make you respond how he wanted you to respond.”

The consensus among those interviewed, even Katz, was Evashevksi was an intimidating figure on campus.

“He was very authoritarian. He was the man,” Katz said. “Nobody argued with him or contested with him.

“The kind of reporting you do today, where you ask tough questions and get after the coach, you didn’t do that with Evy.”

It should come as no surprise that a coach as storied as Evashevski, whose name is usually followed by mention of his two Rose Bowl titles, was as tough as he was on his players.

He was well-known in the Big Ten, after a successful career at Michigan in the early 1940s (Evy was All-Big Ten three-straight seasons). He also was an assistant at Michigan State, among other places before his career eventually led to Iowa.

But every player said he was fair, and the best players, regardless of age or skin color, were going to play.

With Evashevski at the helm, the Hawkeyes were an unstoppable force on offense and an immovable object on defense.

As the 1960 season marched on, so did the Hawkeyes’ quest for another Rose Bowl berth.

On Oct. 22, No. 16 Purdue didn’t go down without a fight, but Iowa prevailed, 21-14, on Homecoming to add another win to the season that was shaping up to be one for the record books.

The next game was another home contest, this time against No. 19 Kansas, which sought to play the role of spoiler.

The Hawkeyes prevailed, 21-7, but not without sustaining a few injuries that proved to be pivotal.

The Hawks, however, had established themselves as the top team in the nation and faced a date with Minnesota, the No. 3 team in the country.

Bill DiCindo, Sherwin Thornson, Mark Manders, and Jerry Williams, all guards, were injured during the Kansas game, weakening the thin offensive line further.

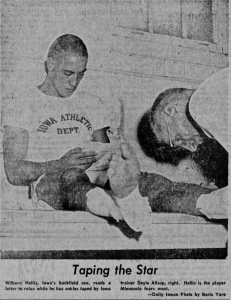

Hollis, left tackle Chester Williams, left tackle Charlie Lee, left end Felton Rogers, and left end Bill Van Buren were also dinged up.

All-American running back Larry Ferguson, fullback Joe Williams, and halfback Jim Robinson each suffered injuries the week before as well.

Again, the parallels appear.

A banged-up quarterback, a patchwork line proven to be effective no matter who was plugged in, running backs tearing up the rest of the conference.

The Hawkeye had not yet lost, similar to the current team continuing without an “L,” but even more, had not been ranked that high in school history.

In front of a sellout crowd in Minneapolis on Nov. 5, 1960, in what was billed as the game of the year, the top two teams in the country met on the gridiron to determine the Rose Bowl berth and, ultimately, the national championship.

“If you lost one game, you probably wouldn’t go to a bowl game,” Hollis said.

“They were just as big a rival as Notre Dame,” Wyatt said. “It was worth more because it was in the conference.”

Hollis said he was ready, that the Hawkeyes were going to beat Minnesota, but he never got the chance.

Many fumbles had gone the Hawkeyes’ way all season. But one did not.

The fumble that cost the Hawkeyes a shot at immortality in the hearts of the Hawkeye fans happened on the goal line.

Hollis said he and Ferguson fumbled a pitch, recovered by Minnesota. Hollis is sure that Ferguson would have scored.

The first-teamers were benched following the mishap.

Down early to the Gophers, Evashevski saw the season slipping away and put in the second-team offense with hopes of sparking a comeback.

The comeback that had happened in so many previous games did not happen. The Hawkeyes fell to the Gophers, creating the only blemish on an otherwise storybook season.

“We would have found a way to win that game,” Hollis said, but hindsight is always perfect.

Minnesota jumped out to a 7-0 lead, but the Hawkeyes quickly answered with a field goal set up by the legs of Ferguson.

It marked Iowa’s only points before a late touchdown. Minnesota won the game 27-10.

“Minnesota didn’t beat us; it was the team we played the week before,” Hinton said. “We beat them eventually by a pretty good margin, but they really dinged us up,”

The accumulation of a season’s worth of injuries, combined with the physicality of Minnesota and the high stakes of the game, proved too much.

The quest for the perfect season ended abruptly.

With two weeks to go in the season, however, the Hawkeyes were not shot out of the sky just yet.

Evashevski rallied the troops with promises of a Rose Bowl berth if Iowa could beat Ohio State, which it did handily in a 35-12 thumping.

A date with hated rival Notre Dame, in which Katz said the players dedicated the game to Evashevski, was all that was left. The Irish proved no match for the Hawkeyes.

But the damage had been done on Nov. 5. Minnesota and Iowa had tied for the Big Ten title, but the Big Ten rules limited its teams to only one team appearing in a bowl game, the Rose Bowl.

The tie-breaker rule did not work in the Hawkeyes’ favor, either.

The Hawkeyes went on New Year’s Day 1959, and Wisconsin went the following year, meaning the Gophers got the berth and were eventually crowned the national champions.

In what amounted to a punch to the gut, the Hawkeyes did not play in the postseason. They finished No. 2 in the country, with an 8-1 record and with wins over six ranked teams.

And yet, the 1960 Iowa football team has since faded from memory.

Not only did the Hawkeyes not go to the Rose Bowl, Hinton said, Evashevski, who unlike many coaches in the nation fielded an integrated team, would not have taken them to any other bowl game because of Jim Crow segregation in the South, where a majority of the nation’s bowl games were played.

But there’s a reason they aren’t among the teams people talk about. People remember 1959, 1985, 2002 as if they happened yesterday.

But there’s a reason they aren’t among the teams people talk about. People remember 1959, 1985, 2002 as if they happened yesterday.

Brad Banks, Chuck Long, Duncan still seem to suit up in the minds of those who saw them play.

More recently, there’s still talk of Drew Tate’s pass to Warren Holloway to win the Capital One Bowl. You remember where you were, no matter how old you were.

The ’09 team produced one of the greatest sound bites in Hawkeye history, Ricki Stanzi’s “love it or leave it,” bested only by Nile Kinnick’s 1939 Heisman speech, played before every game, that still elicits a roar from the crowd.

Winners get remembered, and the Hawkeyes did a lot of winning in 1960, but it’s the bowl-game slight that stings the most, especially when a 6-6 team could make the post season today with a berth in such bowls as the Music City and TaxSlayer Bowls.

“It’s ridiculous, it’s absolutely crazy, it was unheard of for a team to lose six games and go to a bowl game,” Hollis said.

The current Hawkeyes, who have a chance to match the Hawkeyes of lore, have their sights set much higher than those 6-6 bowls, and they have the chance to go well beyond those bowls.

Perhaps some are even Pasadena dreaming, if only for a moment.

But again, just as in 1960, the Gophers can play the role of spoiler. Although Minnesota is only 4-5 in 2015, a win Saturday gets the Gophers one game closer to a bowl-game berth. A loss would knock the Hawkeyes out of playoff contention.

And though Iowa may have gotten a bad bounce in 1960, there may have been many other factors.

Whatever the reason, the Hawkeyes who served in Evashevski’s final season as coach have faded from memory.

“It’s bittersweet; it’s a lot of sweet, but it’s a lot of bitter, too,” Hinton said.

The players don’t know how they would have fared against recent Hawkeye teams, although undefeated records for the two teams, prior to Minnesota, suggest a close matchup. Most of the old players cite the difference in eras and the new way the game is played as major factors in the inability to predict the outcome.

But the Hawkeyes do know this — 55 years ago, they had a damn good team.

“We had some great athletes on that team,” Hollis said. “Maybe it’s that because we didn’t go to a bowl game, nobody remembers us.”